Healthy Farming, Healthy Planet: The Environmental Case Against Tobacco Farming

DG’s Tobacco Control Data Initiative (TCDI) aims to improve access to country-specific tobacco control data for governments, civil society, and academia, supporting better tobacco control policy design and implementation. The six country-specific TCDI websites present data and information on tobacco control through rigorous primary and secondary research. We’ve spoken at length about the health burden and harm caused by tobacco use, but did you know that tobacco farming is deeply harmful to the environment as well? While all agriculture has an environmental impact, tobacco is unique in that every stage of the tobacco lifecycle–from the production and consumption of tobacco to farming and disposal of the final product–wreaks havoc on the environment.

In this piece, we’ll introduce the lifecycle of producing and using tobacco and explore the requisite environmental impact:

1. Cultivation:

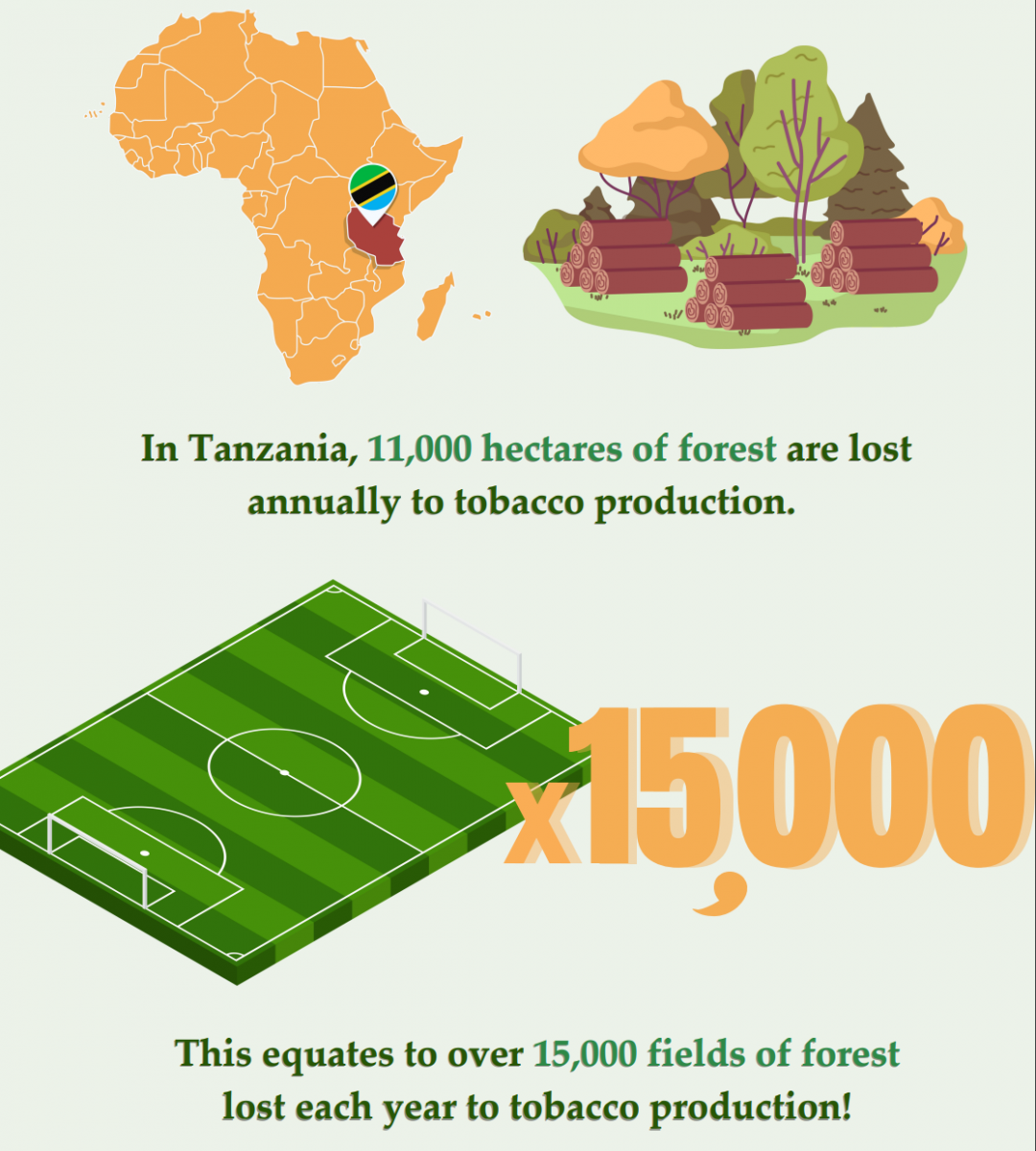

The first stage of the process is cultivation, or growing tobacco. Tobacco farming is a direct cause of deforestation, as farmers have to clear woodland reserves to prepare the land for tobacco cultivation. Tobacco-related deforestation accounts for up to half of the total annual loss of forests and woodlands. Additionally, early 90 percent of tobacco agriculture in Africa occurs in the Miombo ecosystem, the world’s largest contiguous area of tropical dry forests encompassing Tanzania, Malawi, and Zimbabwe.

Source: Land Degradation and Development Journal, Volume 28, Issue 8

Deforestation has wide-reaching effects, threatening plant and animal diversity and whole ecosystems, leaching soil nutrients, and spilling toxic pesticides and fertilizers into soil and water systems. In short, deforestation contributes significantly to climate change, soil erosion, reduced soil fertility, and disruption of soil and water systems, causing undue harm to ecosystems and people.

2. Curing:

Curing refers to the process of drying the tobacco leaf. In this step, tobacco leaves are transported to a curing barn to be dried. A commonly used method for drying the tobacco leaf is “flue-curing.” Flue curing is when the leaves are hung into curing barns and dried from heated air. This approach requires flue-curing barns that are heated by externally fed fireboxes. A distinct odor, texture, and color develop as the leaves lose their moisture.

Small-scale tobacco farmers typically supply these fireboxes with wood chopped from forest reserves to feed these fireboxes. This reliance on wood for curing further contributes to deforestation, and burning this wood emits environmental pollutants, compromising air quality.

3. Processing and Trading:

In this stage, the cured tobacco leaves are sorted into grades and shipped to manufacturing plants. Many tobacco grades exist, and these are based on subjective visual characteristics such as stalk position, leaf size, texture, maturity, and color. This is a vigorous and highly labor-intensive activity because the quality inspection process and subsequent grade classification is done completely manually. Cured leaves must be sorted into homogeneous lots to be inspected. The whole process is contingent on one expert’s subjective assessment of the tobacco leaves. The grade a tobacco leaf receives determines the price a buyer would be willing to pay based on its determining value. Greenhouse gasses are emitted during the tobacco transportation and distribution process.

4. Manufacturing:

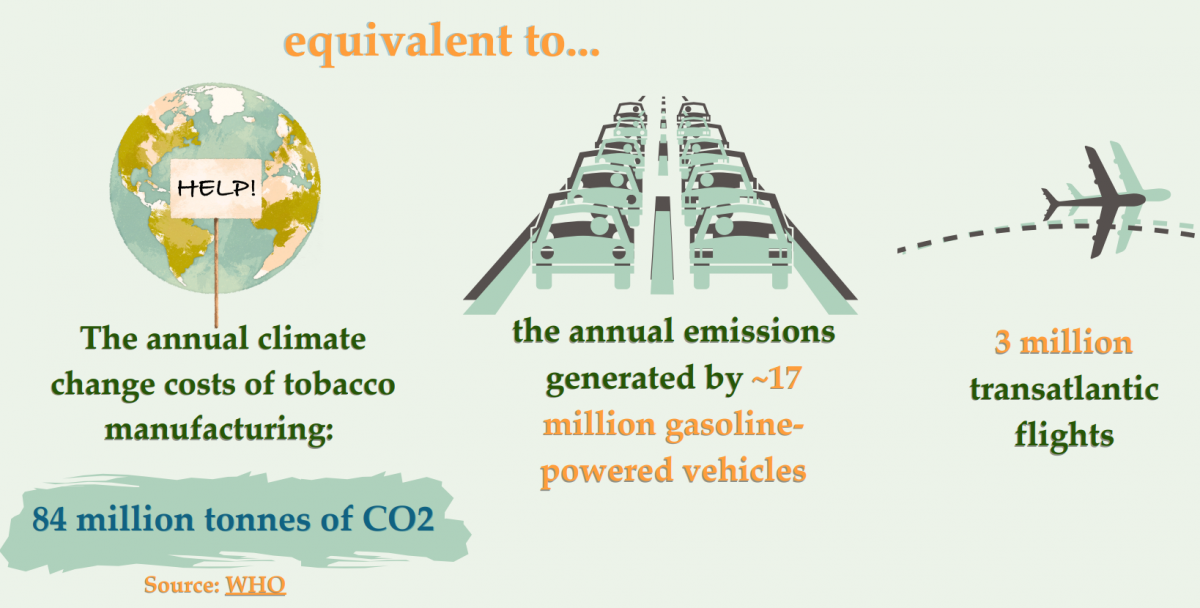

Tobacco is rolled into cigarette paper with filters and packaged for distribution. The manufacturing process also produces other waste products and emits greenhouse gases. According to the World Health Organization (WHO), 84 million tonnes of carbon dioxide (CO2) are emitted annually during manufacturing and into the environment.

5. Distribution:

Cigarettes are shipped to retailers to be sold. Similarly to stage 3 (processing and trading), greenhouse gasses are emitted during shipping. Importing and distributing tobacco leaves–from manufacturers to wholesalers and retailers–via various means of transport (air, boat, car, rail) generates a significant environmental burden.

6. Consumption:

Cigarettes are lit to be consumed. Smoke from cigarettes and other smoked tobacco products releases toxic chemicals into the air, causing undue harm to the environment and people. Greenhouse gases such as carbon dioxide, methane, formaldehyde, and nitrous oxides are also found in tobacco smoke; these chemicals have been found on surfaces months after smoking has ceased.

7. Disposal:

Improper disposal of cigarette butts on streets and sidewalks pollute the environment, particularly water systems. Given that up to two-thirds of cigarettes are improperly disposed of on the ground, these often end up in water systems. There are hundreds of thousands of cigarette butts polluting the ocean. Notably, only one cigarette butt in one liter of water–for a single day–will kill half of the fish exposed to that water for a mere four days. Cigarette filters constitute the second-highest form of plastic pollution worldwide. Not only are cigarettes and filters polluting the environment with plastic, but cigarette filters contain cancer-causing chemicals and other dangerous toxins, the long-term effects of which are still unknown.

Furthermore, most cigarette butt ingredients are not biodegradable and need light to break down, which can take up to a decade!

The costs of cleaning these littered tobacco products do not fall on the culprits–the tobacco industry–but on taxpayers. The numbers are staggering–it costs China nearly $3 billion, India roughly US $766 million, and South Africa approximately $117 million.

Alternative Crops to Tobacco

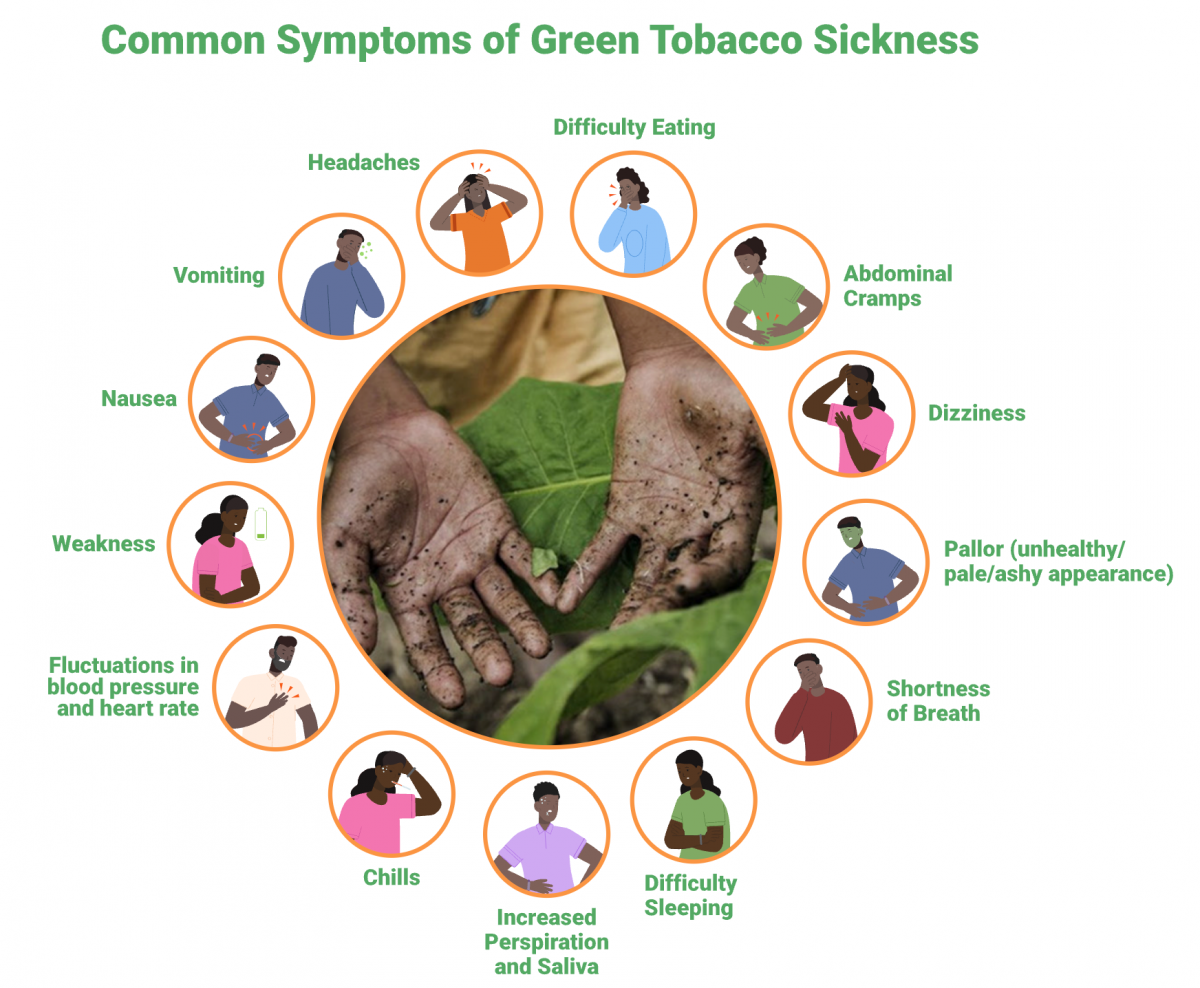

The tobacco crop drains more nitrogen, phosphorus, and potassium than comparable crops, making the soil unsuitable for growing different crops. Given that tobacco farming is labor-intensive and harvesting is done by hand, farmers are exposed to numerous agrochemicals that put them at risk of disease. Specifically, farmers and farm workers remain at risk of developing a form of nicotine poisoning known as “Green Tobacco Sickness,” caused by the transdermal absorption of nicotine from handling tobacco plants. Hand harvesting remains preferred because tobacco leaves mature at different rates, machinery is expensive, and leaves picked mechanically are of lower quality.

Illustration featured on TCDI Zambia Dashboard

Additionally, tobacco workers are highly susceptible to developing ‘tobacco worker’s lung’ and other respiratory diseases. Symptoms of respiratory disease include chest pain, rhinitis, and asthma. Breathing in tobacco mold and dust during curing, baling (compacting leaves into bales), storage (in the home, mainly), and sheeting (tying tobacco into burlap sheets) are some of the many causes of these respiratory problems.To enable the successful uptake of alternative plants, governments must address the array of factors influencing crop choices. These include (but are not limited to):

- Environmental: Land characteristics, types of soil, weather seasons, proximity to water sources, roads, and urban cities

- Farm and Household Characteristics: Household size, educational level, gender, farm equipment, land size, and food security.

- Financial, Technical, and Market Support: Assured markets, credit accessibility, extension services, and soil type sustainability.

Smallholder farmers in Africa often grow tobacco because it is perceived as one of the few economically viable crops. The promise of high returns, market stability, and incentives from the tobacco industry make it an attractive option. However, this perception is shaped by limited access to information, credit, and markets for alternative crops. Barring sufficient support from governments and NGOs, farmers may feel trapped in a cycle of dependency on the tobacco industry despite the environmental degradation and health risks involved.The Tobacco-Free Farms Project, a joint initiative between the World Health Organization (WHO), the World Food Programme (WFP), and several specialized agencies of the United Nations, was launched as a pilot project in Migori County, Kenya in 2022. The project aimed to help farmers sustainably transition from growing tobacco to alternative food crops that do not bear such a significant environmental and health burden and are backed by long-term market stability. By switching from tobacco to high-iron beans in Migori County, it was found that farmers are earning at least three times more!

Conclusion

In sum, the harms caused by tobacco products’ lifecycle–from the cultivating, curing, processing, and trading stages to the manufacturing, distribution, consumption, and disposal phases–are detrimental to the environment. The above mentioned effects are pervasive, impacting the earth’s air, water, land, and tobacco farmers. On this Clean Air for Blue Skies Day, we hope this piece underscores the need for governments and civil society to help farmers sustainably transition from growing tobacco to alternative food crops that do not bear such a significant environmental and health burden.