The Future of Food Systems: Spotlight on Ethiopia

When we discuss food systems, we are not just talking about farms; we are referring to the entire food supply chain. We are talking about how people eat, live, and navigate an increasingly volatile climate.

The upcoming 2025 UN Food Systems Stocktaking Moment (UNFSS+4) provides a global platform to take stock of this complexity, and Ethiopia’s role as host is significant, offering a concrete case study to assess progress not only in policy but also in the lived realities of farmers, students, researchers, and urban households. While Ethiopia’s experience is specific, the challenges and innovations it reveals are common across many low- and middle-income countries.

This blog post analyzes Ethiopia’s national food systems strategy as an example of where the UNFSS can go next in strengthening global food security.

What People Often Miss About Food Systems

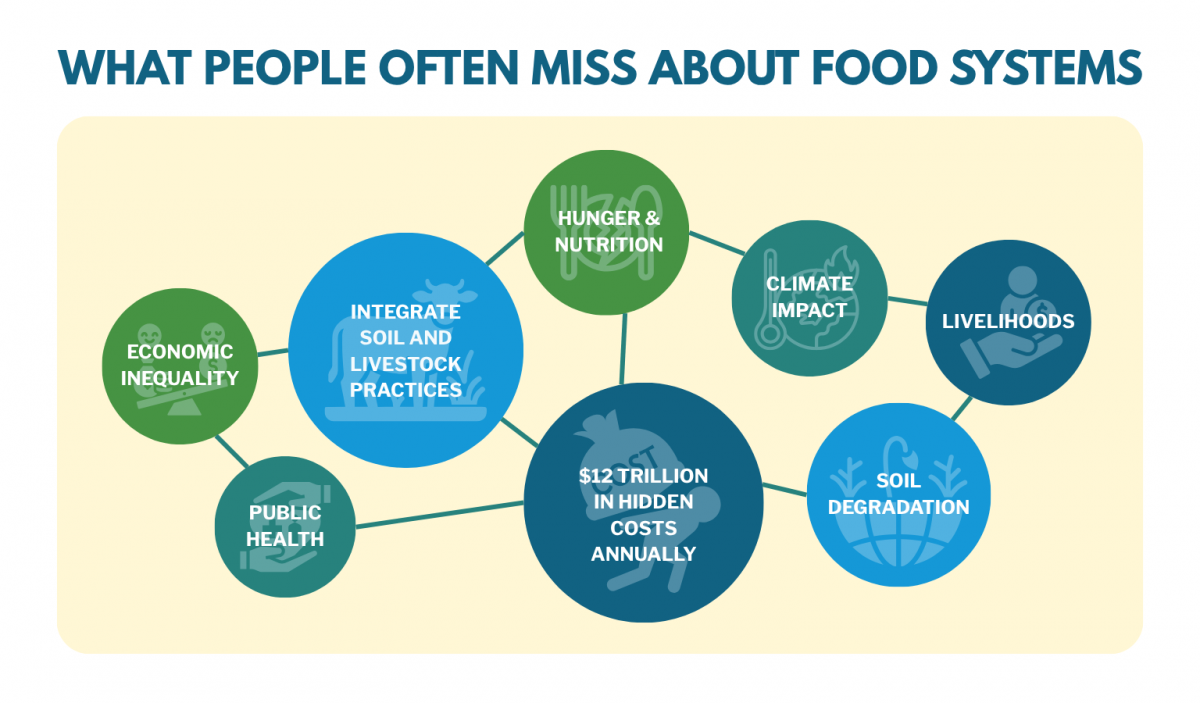

Food systems are often misunderstood as being limited to agriculture alone. In truth, they touch nearly every aspect of life, including land use, climate resilience, nutrition, hunger reduction, and economic opportunity. At their core, food systems have the potential to end hunger not just in Ethiopia, but around the world. By strengthening how food is produced, processed, distributed, and consumed, global food systems can ensure that more people have consistent access to affordable, nutritious food.

Strong, inclusive systems can support smallholder farmers, improve distribution networks, and create safety nets that protect the most vulnerable from food insecurity.

At the same time, food systems are contributing to rising rates of chronic disease and environmental degradation. These patterns not only strain ecosystems but also increase the burden on public health systems. Meanwhile, today’s food systems are estimated to generate over $12 trillion in hidden costs according to the Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO). Less than five percent of climate finance is directed toward fixing them.

Ethiopia: An Example of What’s Working So Far

Ethiopia presents encouraging examples of what’s possible. It has prioritized soil health through investments in soil mapping and regionally adapted fertilizer blending, as outlined in AGRA’s Ethiopia Strategic Plan (2023–2027), which supports national efforts to improve fertilizer quality and expand localized blending. Social safety nets, such as the Productive Safety Net Programme, also continue to play a critical role in protecting vulnerable households from food insecurity.

Progress in digital agriculture has also been notable. The country’s Digital Agriculture Roadmap outlines plans for interoperable systems linking farmer registries, market data, and advisory services. These goals align with regional aspirations for modern and inclusive agriculture. Youth engagement has also been meaningful. For instance, Ethiopia’s Green Legacy Initiative has mobilized millions of young people to plant trees and promote environmental stewardship nationwide. In schools, projects such as the Youth in Horticulture, an initiative by the Farm Secure Schools Africa, have combined hands-on gardening with nutrition education, encouraging students to participate directly in sustainable food systems.

The Gaps We Can’t Ignore

Still, significant challenges remain. One is the disconnect between livestock farming and soil management. Ethiopia’s Livestock Information System Roadmap focuses on veterinary services and disease tracking but does not connect livestock practices, such as manure recycling, to soil health strategies. This siloed approach misses a key opportunity for integrated land management. Countries such as Senegal face similar challenges, where livestock and soil health are addressed in parallel rather than in a coordinated way.

Another concern is the lack of quality control for fertilizers. While local blending has expanded, there is no dedicated public budget for laboratory testing. As a result, quality oversight is left to market forces. Kenya also implements a fertilizer subsidy scheme, but its quality assurance system is undermined by limited laboratory capacity and insufficient regulatory enforcement.

Water insecurity also remains unaccounted for in Ethiopia’s food policy framework. Although crop yield data is available, there is limited information on post-harvest losses or household-level food stress. Tools such as the Household Water Insecurity Experiences (HWISE) scale, which measures personal experiences of water-related hardship, could be adapted for this purpose.

Ethiopia’s digital agriculture framework remains focused on national implementation and rollout. While it demonstrates strong internal coordination, it does not yet incorporate the African Union (AU)’s standards for data governance or commit to the continent-wide digital infrastructure promoted by the AU Digital Agriculture Strategy. This limits opportunities for collaboration across national borders. A similar pattern is observed in Vietnam, where promising digital tools have emerged but remain disconnected from regional strategies. These examples show that many of Ethiopia’s food system challenges mirror wider global patterns.

What Ethiopia’s Case Tells Us About What Needs to Happen Next

To move from commitments to fundamental transformation, clear and actionable steps are needed. One critical issue raised in Ethiopia’s food systems strategy is that key sectors such as soil health, livestock, and digital agriculture are advancing in parallel but not in coordination. For example, the Livestock Information System Roadmap and Integrated Soil Fertility Management Manual are each robust in their own right. However, they fail to link grazing practices and manure reuse to soil restoration goals. Bridging these silos is essential for building a truly integrated and sustainable food system.

These priorities reflect a progression from integrated soil-livestock management toward broader systems coordination, with a growing focus on digital infrastructure, monitoring, and youth leadership.

Below are key recommendations for Ethiopia, as well as broader global priorities aligned with the UN Food Systems agenda.

For Ethiopia:

- Integrate livestock nutrient cycling into national soil management strategies, linking manure use and grazing to soil fertility.

- Establish public-private laboratories for fertilizer quality testing, supported through the Nairobi Declaration on Healthy Soils

- Align the Digital Agriculture Roadmap with interoperability and governance standards endorsed by the African Union.

- Enhance water measurement tools by incorporating community-based indices, such as the HWISE scale.

- Ensure that youth have permanent representation in food system governance structures.

- Streamline national indicators in the Comprehensive Africa Agriculture Development Programme (CAADP) reporting, with emphasis on: i)the share of land under sustainable management; ii)the adoption rate of digital agriculture tools; and iii) the uptake of climate-smart agricultural practices.

For the UN Food Systems Agenda:

- Scale support for blended finance models that link private investment to public agriculture priorities.

- Expand investment in localized, data-driven tools that empower smallholders and local governments.

- Encourage concrete commitments to enhance the integration of livestock, water, and soil strategies to enable ecosystem-based planning.

- Encourage UN member states to adopt shared digital infrastructure and data standards for better regional coordination.

- Highlight youth innovation hubs, school-based agriculture programs, and leadership pipelines that exemplify how the next generation can own food systems development globally.

This dual focus on national implementation and global coordination is critical for achieving real progress before the next review cycle.

The Moment is Now

As one of many countries navigating food system transitions, Ethiopia’s progress, while uneven, offers valuable insights for peers around the world. The challenges it faces are not unique. Countries from West Africa to Southeast Asia are grappling with how to turn national food systems commitments into integrated, accountable action. These shared struggles highlight the need for stronger coordination, more transparent monitoring, and greater alignment with regional frameworks. The UNFSS Stocktake moment is the perfect opportunity to double down on technical support and promotion of the integration of food systems that support everyone.