Arrays, Objects, and Trees: A Look at JSON-formatted Contracting Data

The Open Impact Day conference hosted in Washington, D.C. this past month highlighted examples of open data in improving trust between citizens and their governments. In Ukraine, a recently launched website named Prozorro gives users an unprecedented look into the government’s procurement process. The technical processes at work within websites like Prozorro, however, may still confuse some open data users. This post seeks to elaborate on this technical background by showing an example of how users can employ statistical software to analyze contracting data.

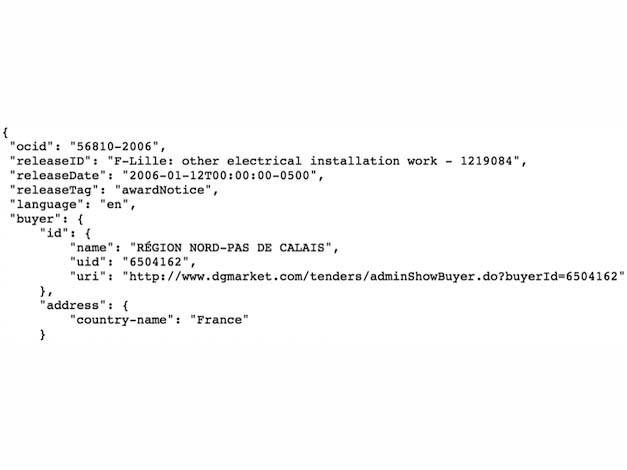

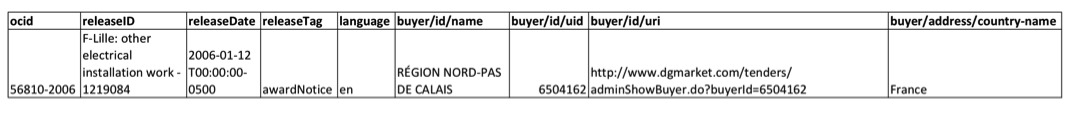

Databases following the Open Contracting Data Standard (OCDS) store their data in a format called JavaScript Object Notation (JSON). JSON, unlike other formats such as comma separated values (CSV) that use a tabular mode of displaying data, displays data in a “tree” format, nesting different objects and arrays inside each other. For example, this JSON excerpt:

Would be formatted as this table in a CSV:

Notice that this table splits the “buyer” field into four different fields, while the JSON example formats the same field into a neater tree of variables, saving space and making the data better organized. This makes JSON often the best way of formatting contracting data where even more fields and values are present. However, while JSON is the preferred language of techies and is becoming the most frequent formatting of Application Program Interfaces (APIs), many open data users may find JSON formatted data harder to use for data analysis.

In order to show how JSON-formatted data can still be analyzed, I examined our very own EU Public Contract Database, published last year. This database contains over 2,000,000 contracts from 2006 to 2014 in over 28 European countries. To extract the data, I used R, the free and open source statistical analysis software, and RJSONIO, an extension package that allows users to convert JSON content to R objects. The process enabled me to take a massive database and split it up into readable chunks.

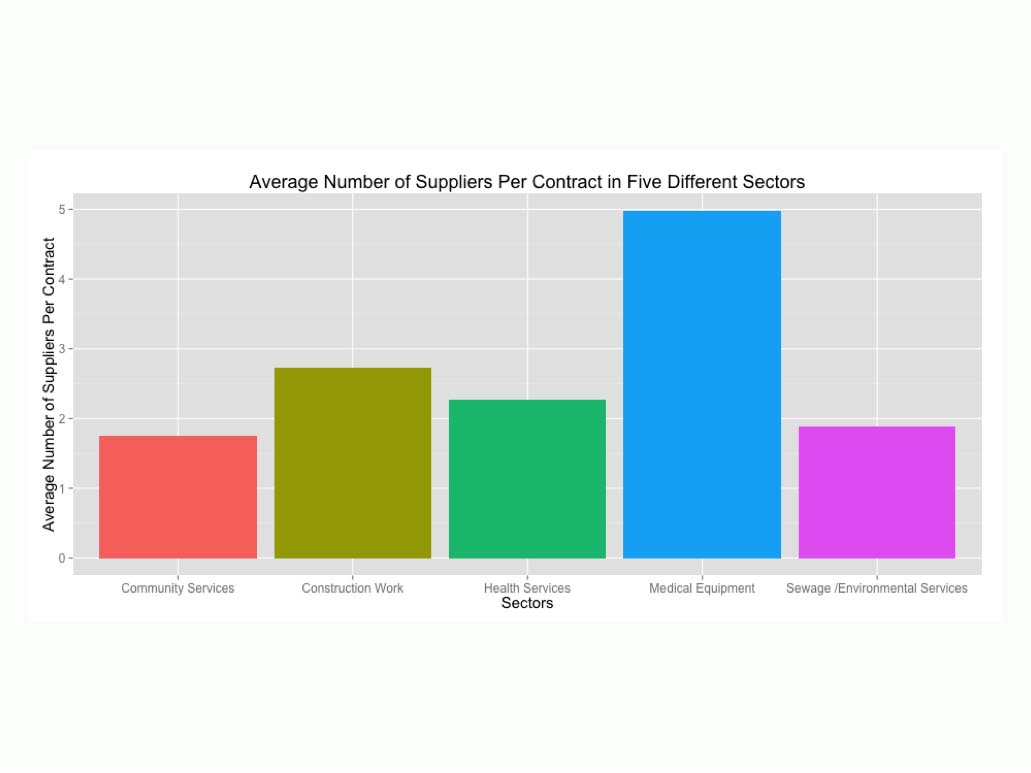

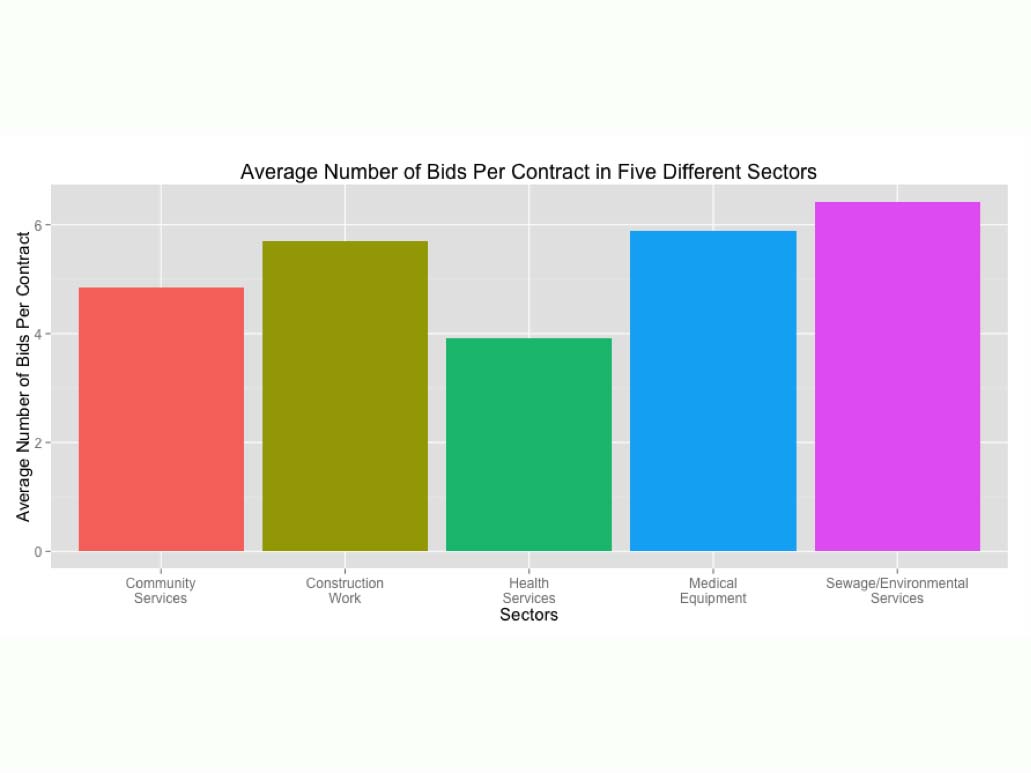

Using ggplot2, a data visualization package for R, I was able to graph certain interesting trends hidden in the database. For all of the following graphs, I decided to focus on contracts in the United Kingdom in 2013, since this part of the database offered a diverse variety of contracts to easily analyze.

Below is a graph showing the average number of suppliers awarded for each contract in five different sectors. The fact that a wide variety of pharmaceutical companies specialize in different drug types could explain the high amount of suppliers in the Medical Equipment and Pharmaceuticals sector relative to the other sectors.

Below is a graph showing the average number of bids per contract in the same five sectors. Notice that the high number of bids correlates with a high number of suppliers per contract in the Medical Equipment sector, but seems to differ widely in the Sewage/Environmental Services sector. Explanations for this pattern will require further research of how firms within these sectors operate, and how oligopolistic/monopolistic these sectors are.

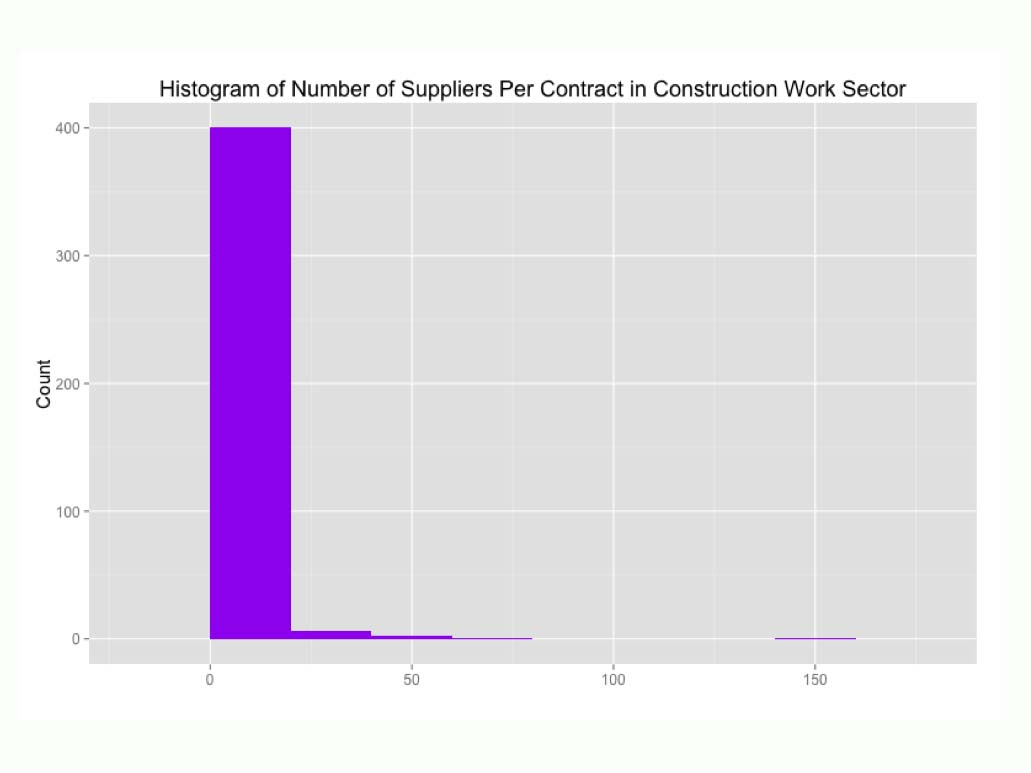

Below is a histogram of the number of suppliers per contract within the construction sector.

You can see that there’s one contract that sticks out in particular: the one with over 150 suppliers, a number that vastly exceeds the average amount of 2.735. This contract, related to construction work in Glasgow, contains zero information regarding its financial value or its bidding process. While there is still not enough information to make any conclusions about the validity of this contract or the process through which it was procured, this example shows how users can spot interesting patterns and possible anomalies quickly using JSON-formatted contracting data that follows the OCDS.

Governments and civil society will require a greater depth of information within contracting data if they want greater use out of it. Version 1.0 of the OCDS has addressed most of these concerns, but certain issues still remain. Geographical location of contracts, for example, should be fully integrated into the standard. And users will need to pressure publishers to provide more detailed information on a contract’s bidding process, since this step of the procurement process represents a significant opportunity for collusion or fraud.

As the OCDS advances, we hope that more people will take a closer look at other procurement databases and see what insights can be gained from deeper analysis.

Share This Post

Related from our library

Introducing The HackCorruption Civic Tech Tools Repository

Introducing the Civic Tech Tools Repository: an open-source hub of digital solutions to fight corruption. Designed for growth through GitHub contributions, it brings together tools, code, and resources across six key areas for HackCorruption teams and beyond.

Building a Sustainable Cashew Sector in West Africa Through Data and Collaboration

Cashew-IN project came to an end in August 2024 after four years of working with government agencies, producers, traders, processors, and development partners in the five implementing countries to co-create an online tool aimed to inform, support, promote, and strengthen Africa’s cashew industry. This blog outlines some of the key project highlights, including some of the challenges we faced, lessons learned, success stories, and identified opportunities for a more competitive cashew sector in West Africa.

Digital Transformation for Public Value: Development Gateway’s Insights from Agriculture & Open Contracting

In today’s fast-evolving world, governments and public organizations are under more pressure than ever before to deliver efficient, transparent services that align with public expectations. In this blog, we delve into the key concepts behind digital transformation and how it can enhance public value by promoting transparency, informing policy, and supporting evidence-based decision-making.