Mapping Maternal and Neonatal Health Trends: The PREMAND Project

Despite public health progress in many areas, mortality rates for mothers and newborns in low-resource environments remain stubbornly high – even where other health metrics have improved. Understanding why is a high priority for public health practitioners. Understandably, much of this data focuses on clinical causes of death: biomedical reasons like sepsis (infection) or hemorrhage.

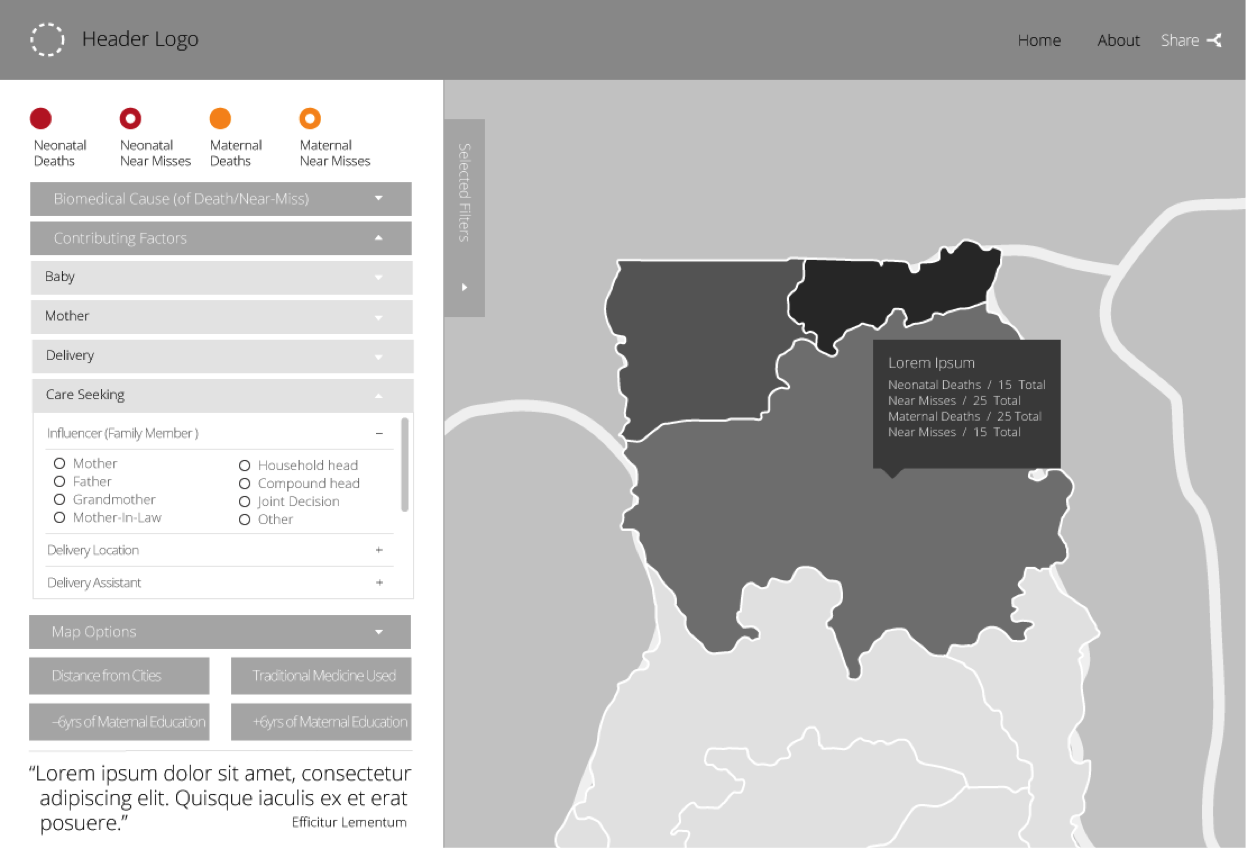

But, important as these clinical causes are, they do not happen in a vacuum. The PREMAND project – PREventing Maternal and Neonatal Deaths – is seeking to supplement clinical data with a better understanding of the social and environmental factors that affect outcomes for mothers and infants in northern Ghana. Development Gateway is building a tool to map that data, with the aim of helping communities and health workers better understand the role social and environmental factors play and how those factors vary by community and population.

The mapping dashboard will include data not only from maternal or neonatal (newborn) deaths, but also from “near misses” – cases where a mother or baby became very ill and could have died, but recovered instead. Capturing this information allows for comparison and analysis: which social and environmental factors are different, and thus may contribute to whether a mother or infant recovers?

In four districts in northern Ghana, the team has been working to gather information on deaths and near misses via verbal and social autopsies. These involve in-depth interviews with families and community members, in order to understand what happened.

In the case of PREMAND, field workers are also collecting information about factors beyond the biomedical cause of death. For example: How far away is the nearest health clinic? Is there a way to get there? Did the mother get prenatal health services? Did she need to get permission from someone else before seeking medical care? How many years of education does she have? Did the family use traditional medicine? Was there a problem at the health facility that prohibited or delayed care?

This kind of analysis is sometimes framed in terms of the “three delays”: a delayed decision to seek care, delayed arrival at a health facility, and delay in receiving adequate care. PREMAND seeks to tease apart those categories even further, to understand the underlying factors that drive these delays.

DG’s role is to take this information and visualize it geospatially in a way that provides analytical insights for health providers and clear messaging for local communities. (Exact locations will be blurred and private details removed, given how personal this information is.) Our plan is to bring to the surface observable patterns using a robust set of filters to highlight the relationship between variables. These relationships could be things like: “Location of sepsis-related infant deaths relative to traditional umbilical cord care practices,” or “Locations of maternal deaths vs near-misses relative to health facilities.”

To plan a tool like this, we believe strongly in the power of wireframing. Sketching out how the dashboard could look makes us think through how it should actually work. This generally brings to light a lot of important questions about the data structure as well as our goals for the user: what should we show, and how?

It also makes sure we’re on the same page as our partners – in this case, the University of Michigan team leading the project, as well as stakeholders in Ghana – who provided input on the latest mockups. Below is an early wireframe for the PREMAND dashboard, still a work in progress.

Our goal is to do justice to the nuances of this data without losing sight of the big picture. Users should be able to gain general insights without a lot of effort, but also have the option to dig deeper when they want to. In this way, we hope the tool will contribute to the landscape of public health informatics – and show that mapping a community’s unique social and environmental needs can lead to more tailored, effective interventions.

PREMAND is supported by USAID/Ghana, the Navrongo Health Research Centre and University of Michigan.

Project Team: Fernando Ferreyra, Galina Kalvatcheva, Liliana Mercado, Martha Staid, Llanco Talamantes

Share This Post

Related from our library

Beyond Kigali: Where Does Africa Go from Here with AI?

As governments, funders, entrepreneurs, and technology leaders rally around the AI moment and move towards actions, at Development Gateway, we are asking a different set of questions: Where is the data, and what is the quality of the data behind the algorithms? How will legacy government systems feed AI tools with fresh and usable data? Are Government ministries resourced to govern and trust the AI tools that they are being encouraged to adopt?

Stakeholder, Where Art Thou?: Three Insights on Using Governance Structures to Foster Stakeholder Engagement

Through our Tobacco Control Data Initiative (TCDI) program and its sister program Data on Youth and Tobacco in Africa (DaYTA), we have learned that creating governance structures, such as advisory boards or steering committees, is one approach to ensuring that digital solutions appropriately meet stakeholders’ needs and foster future stakeholder engagement. In this blog, we explore three insights on how governance structures can advance buy-in with individual stakeholders while connecting them to one another.

DG’s Open Contracting Portal Designated as a Digital Public Good

Digital Public Goods Alliance designated DG’s Open Contracting Portal as a digital public good in September 2022. The Portal provides procurement analytics that can be used to improve procurement efficiency and, in turn, reduce corruption and increase impact.