Are Results Data from Government M&E Systems Effectively Collected, Analyzed, and Used?

Monitoring & evaluation (M&E) systems are designed to serve at least two purposes: collecting and aggregating data, and analyzing and interpreting those data to inform decision-making. In concert, these activities help governments and donors to make more efficient and effective resource allocations and increase aid effectiveness. A study of 20 government M&E systems in sub-Saharan Africa suggests, however, that data collection often does not lead to data analysis and use, with monitoring frequently ‘crowding-out’ evaluation activities.

This third in a series of four posts presenting evidence and trends from the Evans School Policy Analysis and Research (EPAR) group’s report on aid-recipient government M&E systems focuses on findings on results data collection, analysis, and use. EPAR reviewed evidence from 42 government M&E systems, including 17 general national M&E systems that aim to monitor and evaluate progress across multiple sectors and 25 systems that are national in scope but sector-specific. The first post in the series provides an introduction to aid-recipient country M&E systems and outlines the theoretical framework, data, and methods for the research. Institutionalization and coordination of these systems is the subject of the second post in the series. This post considers the current trends and challenges for data collection and analysis, and also examines the extent to which governments are using monitoring and results information.

Data Collection and Aggregation

Data collection and aggregation are considered basic capacities necessary for a functioning monitoring system. To evaluate any project, program, or policy, appropriate data must be collected, and data from local sources must be aggregated to measure indicators at the regional or national level. Evaluations of country-level M&E systems, however, suggest that capacity for basic monitoring activities is limited by high staff turnover and insufficient funding to provide regular staff training or hire enough qualified workers. Inadequate staff capacity can result in issues with data quality and in a low percentage of data being turned in on time. Further, poorly coordinated M&E activities can lead to duplication of efforts, increasing costs and decreasing efficiency in aggregating data.

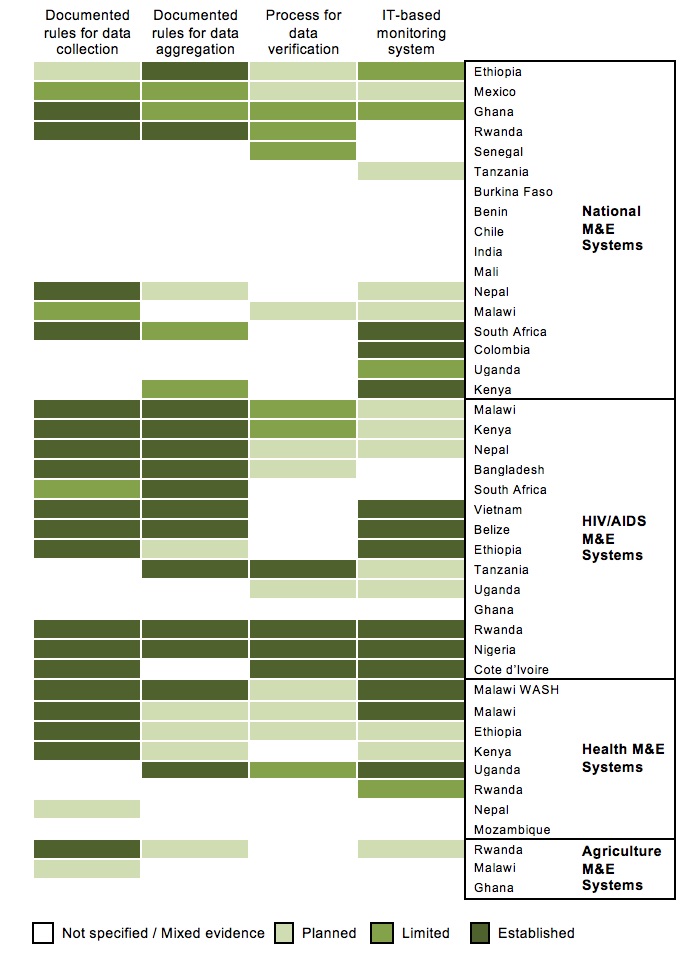

Among the 42 M&E systems reviewed, 19 have established rules for data collection, four have some rules in place but evidence that they are not consistently applied, two have plans for implementing rules, and 17 do not specify any data collection rules. Over half of the systems with established rules for data collection (10 of the 19) are HIV/AIDS M&E systems. A common approach in these systems is to develop tables where the methods and responsibilities for data collection are outlined for each indicator of interest.

Compared to data collection, fewer systems (14 of 42) have established rules for data aggregation, though six plan to create rules. Similarly, the majority of systems with documented rules for data aggregation (10 of the 14) are HIV/AIDS systems, including Nepal’s, where data are aggregated monthly at a central agency. A number of authors note that even otherwise well-developed general national systems have difficulties with data aggregation due to variations in data formats at regional and local levels, for example in Mexico.

Figure 1: Processes for Monitoring in Government M&E Systems

Data Verification and IT-Based Monitoring Systems

Beyond collecting and aggregating data, more sophisticated monitoring capacities include established processes for verifying data quality and incorporating information technology (IT) tools in M&E systems. Data verification processes include periodic data audits and supervisory visits to local data collection centers as well as comparing similar measures from different sources. These processes aim to ensure data quality by checking the validity, reliability, and accuracy of collected data. Most systems (22 of 42), however, do not describe any data verification processes, and only four, all of which are HIV/AIDS systems, include clear rules for verifying data.

Although often constrained by staff technical capacity and availability of electronic infrastructure, IT-based M&E systems can greatly increase efficiency relative to paper-based systems that are still commonly used by many aid-recipient governments at different levels of collecting and aggregating data. Twelve of 42 systems have established IT-based M&E systems that integrate collecting, aggregating, and verifying data, and 12 others describe plans to develop such systems. The remaining 18 systems may also use IT tools for M&E activities, but these tools do not form the basis of their M&E systems. IT-based systems vary in complexity from standardized Excel-based forms to proprietary data management software tools. The Nigeria HIV/AIDS system, for example, uses a tool developed by the Global Fund to review the quality of data submitted from local agencies on a monthly and quarterly basis.

Data Analysis and Evaluation

Many M&E systems are criticized for concentrating on monitoring and ignoring evaluation, and for collecting and reporting information on various indicators without analyzing what the results mean for the effectiveness of government activities and applying that analysis to budgeting and planning. Most M&E systems we review have well-developed output indicators, which allow governments to assess their performance in implementing their strategy. Further, 14 systems conduct or plan to conduct audits of expenditures against budgets to assess implementation performance.

A frequent challenge among the M&E systems we reviewed, however, is an overemphasis on outputs as opposed to outcomes. This focus appears to be especially pronounced in health M&E systems, which regularly track a wide variety of output indicators describing quantities of services provided, but do not track as many outcome indicators measuring effects of those services. While 34 of 42 systems show evidence of tracking changes in outcome indicators over time as a form of basic analysis, just 13 of these explicitly describe how they use before and after data from time series to evaluate the effectiveness of their programs. Only six systems go beyond measuring changes in outcome indicators and also evaluate the cost-effectiveness of their activities.

Twenty-two M&E systems describe specific challenges with their capacity for evaluation. Challenges include insufficient funding and staffing, low levels of training and experience, and weak institutional support for results analysis. Some systems address capacity challenges by supporting internal capacity building, as Chile for example started with simple desk evaluations to build capacity for more complex evaluation. Some systems note, however, that the presence of separate donor M&E systems limits the availability of trained and experienced evaluators to support government M&E systems.

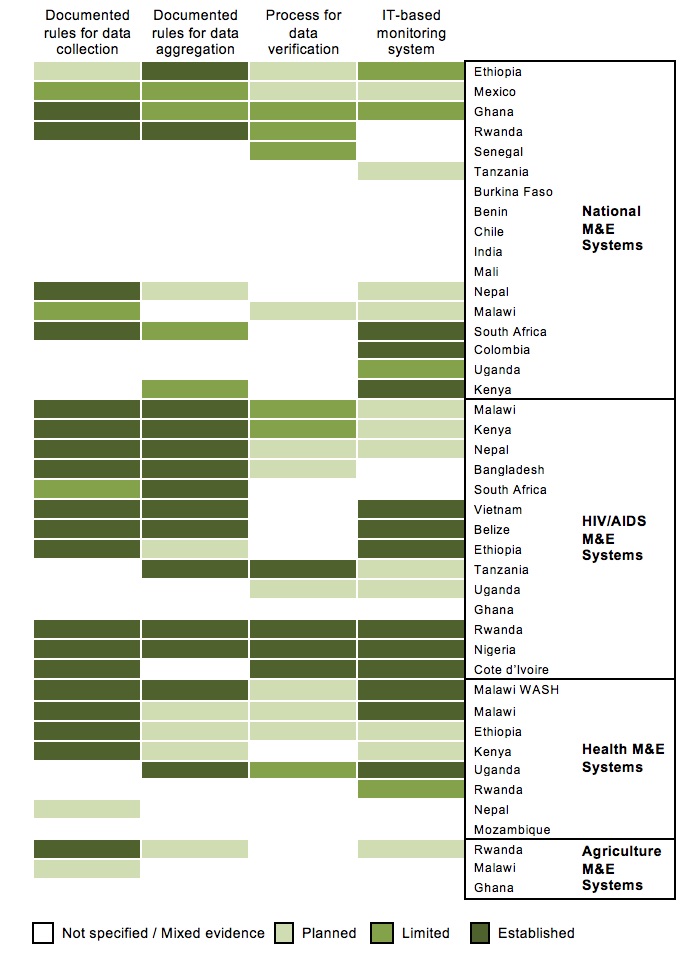

Use of Results Information in Policy / Strategy Planning and Budget Allocations

The end goal of an M&E system is not simply to generate continuous results data, but to provide decision-makers with information to improve performance and achieve intended outcomes. M&E information can be used in a variety of ways, but two important uses are policy and strategy planning and budget allocations. EPAR finds a number of challenges for the use of results information, however, including lack of capacity for analysis, data quality issues, weak links between the M&E system and decision-makers, and absence of a culture of performance-based management.

Among the 42 M&E systems reviewed, only two demonstrate consistently incorporating M&E information for policy and strategy planning through regular review and planning processes. In the Malawi health M&E system, for example, results from annual reports influence the annual work planning and budgeting process, and mid-term reviews are conducted to evaluate progress on the strategic plan and influence the development of future strategic plans. Twenty M&E systems demonstrate more limited use of results information, with some established processes but gaps in how the information is used. The most frequently reported use of M&E information in these systems is in the development of multi-year strategic plans, which incorporate performance and lessons learned from implementation.

In contrast to policy and strategy planning, the use of M&E information in budget allocations is more common. Fourteen of 42 systems regularly use results data and evaluations to guide budget decisions, generally as part of annual plans. In Mali’s national M&E system, for example, the national budgeting process begins with the completion and appraisal of the annual sectoral review.

Figure 2: Use of Results Data in Government M&E Systems

Processes for Using Results Data

Some M&E systems formalize a set of procedures for reviewing M&E information and developing policy and strategy recommendations based on that information. Systematizing these processes can encourage analyzing and using results data to improve performance. Review processes such as annual or joint reviews with stakeholders aim to apply M&E information to planning and strategy decisions, and can involve government bodies at different levels, private sector organizations, civil society organizations, and development partners. Evidence from Colombia’s national M&E system suggests that sharing performance information with stakeholders supports government accountability and can encourage the use of M&E data in planning processes. However, some authors argue that while there is usually demand for M&E data for reporting purposes, this does not translate into high demand for information for planning purposes, and M&E data may be used more as symbolic rather than instrumental tools for improving performance.

Less than half of systems reviewed (18 of 42) have clear, established processes for systematically reviewing M&E information, although 14 others have plans to implement such processes. Seventeen of 42 systems regularly conduct joint or coordinated progress or performance reviews, and another 12 systems describe plans for joint progress reviews. Lacking clear processes for using M&E data appears to be mainly due to low levels of internal demand, which EPAR discusses in an earlier post.

Evidence is mixed on the extent to which aid-recipient government M&E systems effectively collect, analyze, and use results data. Although many systems have overcome staff capacity challenges and developed processes to efficiently collect and evaluate results data, there is no clear link between data collection and effective data use. Additional challenges, such as data quality issues, weak links between the M&E system and decision-makers, and the absence of a culture of performance-based management, hinder some systems in more effectively using results data. The final post in this series examines the role of development partners and their alignment and harmonization with government M&E systems.

References to evidence linked in this post are included in the full report. This series is guest-written by the Evans School Policy Analysis and Research (EPAR) Group at the University of Washington in collaboration with Development Gateway and the Results Data Initiative. View the first and second posts.

Share This Post

Related from our library

Harnessing the Power of Data: Tackling Tobacco Industry Influence in Africa

Reliable, accessible data is essential for effective tobacco control, enabling policymakers to implement stronger, evidence-based responses to evolving industry tactics and public health challenges. This blog explores how Tobacco Industry strategies hinder effective Tobacco control in Africa, and highlights how stakeholders are harnessing TCDI Data to counter industry interference.

Building a Sustainable Cashew Sector in West Africa Through Data and Collaboration

Cashew-IN project came to an end in August 2024 after four years of working with government agencies, producers, traders, processors, and development partners in the five implementing countries to co-create an online tool aimed to inform, support, promote, and strengthen Africa’s cashew industry. This blog outlines some of the key project highlights, including some of the challenges we faced, lessons learned, success stories, and identified opportunities for a more competitive cashew sector in West Africa.

Digital Transformation for Public Value: Development Gateway’s Insights from Agriculture & Open Contracting

In today’s fast-evolving world, governments and public organizations are under more pressure than ever before to deliver efficient, transparent services that align with public expectations. In this blog, we delve into the key concepts behind digital transformation and how it can enhance public value by promoting transparency, informing policy, and supporting evidence-based decision-making.