Defining Decision-Making: Connecting the Dots Between Data and Impact

Strong, data-driven decision-making is critical for transforming the livestock sector and achieving national goals for food security and economic growth. However, we often talk about what is needed to enable strong decisions and the potential outcomes of data-driven decision-making without connecting the dots. What decisions are we actually talking about, between the data on one end and the impact on the other? What does data-driven decision-making actually entail?

This is the first of a four-part blog series, where we will discuss learnings we’ve gleaned from DG’s a Livestock Information Vision for Ethiopia (aLIVE) program, connecting the dots across the livestock data and decision-making network in Ethiopia and breaking down our approach to its many facets.

Designed to center on data-driven decision-making, aLIVE aims to empower decision makers in Ethiopia’s livestock sector by providing relevant, accurate, timely, and digital livestock data and analytics. The goal is to ensure that better decisions will ultimately help Ethiopia meet national food demands and achieve food security while building a robust, more independent economy.

“We are a livestock based country, so having livestock data is very important for trade and the national economy.”

– MoA Key System Owner

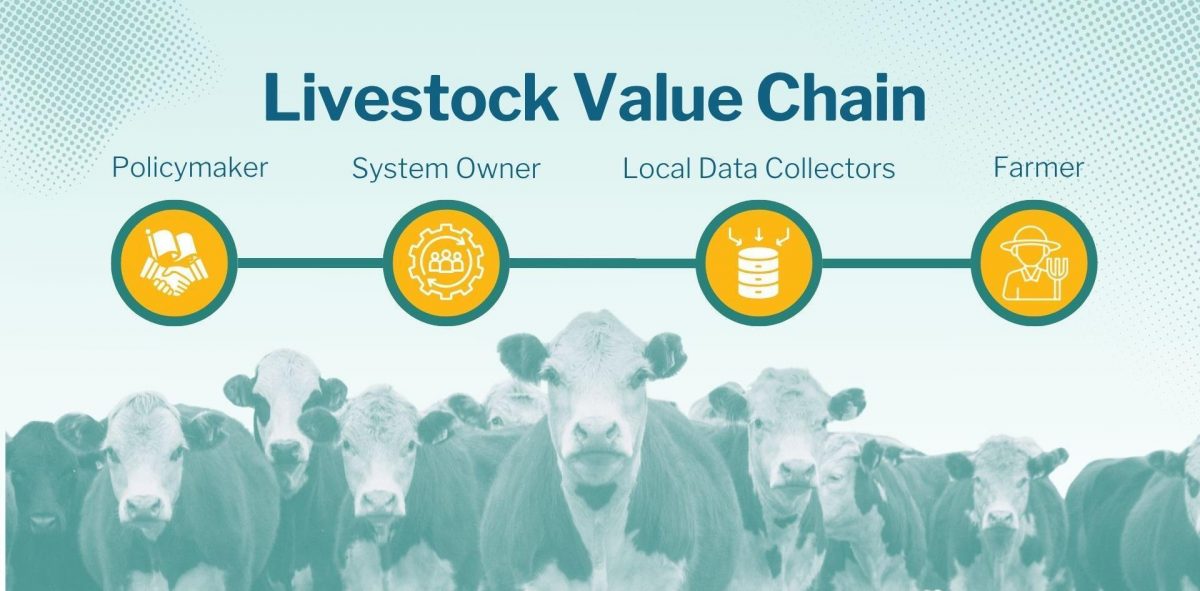

For the aLIVE program, enabling data-driven decision-making means enabling key actors to take timely, evidence-based action based on interoperable livestock data systems. It involves who makes decisions, what kind of decisions, and how data helps. This decision-making takes place at both ends of the livestock value chain – from farmers to leaders in government – and affects each level of the chain.

“Data should flow from the farmer to cooperatives and to the government.”

– MoA Key System Owner

Often, decisions at various levels across the value chain are siloed and disconnected from the impacts on other levels. They are often not data-driven and are disconnected from data produced or collected at other levels of the value chain. When data is not properly fed up and down the value chain – for example, from the farmer to the Ministry of Agriculture (MoA) and back – decisions that impact the farmer level might be made at the Ministry without properly understanding the realities at ground level. At the same time, the farmers who produce and provide data may not understand the big picture without access to government-level livestock data systems and the skills to interpret this information.

The Livestock Value Chain

In aLIVE’s case, the “livestock value chain” refers to producers, managers, and users of livestock data. Each level of this chain impacts and is impacted by livestock-related actions taken at other levels, even when they are not in communication with each other.

At one end of the livestock value chain sits the policymakers. This includes decision-makers, such as ministers at the MoA and Ministry for Trade & Regional Integration (MoTRI), who make choices that affect and shape livestock in Ethiopia. These decisions include those that govern livestock production, regulate trade and manage the health of the livestock population.

“Having proper information and data from the top down is very important for decisions on where to invest in disease control. Knowing the prevalence of each disease in each area is basic to interventions, designing vaccination programs, and even showing strong traceability and transparency to our trading partners. If we don’t have the data, our trading partners won’t trust us.”

– MoA Health Information Systems Lead

System owners, such as those who manage the five key livestock data systems that aLIVE works with, constitute another level in the value chain. These system owners determine how critical livestock data that should inform policymakers is collected, managed, and disseminated.System owners are custodians of livestock data in Ethiopia, meaning that their data management methods greatly influence the quality of livestock information and thus, impact national-level decisions.

“We have fragmented data sources to make national decisions. We need all data users to have the same understanding of the data. This will be easy with a single dashboard and data access in a single click.”

– MoA Key System Owner

System owners play a critical role in connecting and translating information from the ground up, delivering data from farmers to policymakers. In order to do this well, system owners must be empowered data users, able to deliver the data in their systems to decision-makers packaged in a usable, understandable format. This is why the aLIVE program introduced the data use training program, strengthening system owners’ data use skills and visualization tools to improve quality, efficiency, and a culture of data use at the MoA – more on this in the next blog in this series.

Local enumerators spread across the country at regional, zonal, woreda (a district in Ethiopia), and kabele (a ward in Ethiopia) levels collect essential livestock data from the ground, which is then fed into national-level data systems. These data collectors play a key role in feeding data from the regions and transmitting it to the federal level. Therefore, the quality and completeness of the data they collect, as well as their collection methods are critical for providing the data needed to populate the livestock systems and to accurately inform the decision-makers who use these systems.

At the other end of the livestock value chain is the farmer. Farmers generate critical ground-level data on livestock, including population, health, and genetics. At the same time, decisions on the farm are regulated by government-level livestock decisions.

“From the public’s perspective, having livestock information is huge because the majority of people’s resources come from their animals.”

– MoA Key System Owner

Thus, the accuracy of livestock data in the five key systems is crucial, especially given the potential impact at the household level. Farmers stand to benefit not only from properly informed policy but also from access to and understanding of data collected from across the country and fed into livestock data systems.

Private sector actors also fit into the livestock value chain, both as data producers and decision-makers. Their decisions can affect aspects such as livestock markets, trade, and traceability. In turn, they are influenced by factors such as export policies, regulatory requirements, and farm-level data. Like farmers, private sector actors can benefit from properly informed policy, as well as access to and understanding of the data in the five key livestock data systems.

“Traders may be focusing on their own business without proper awareness of the big picture. With strong data, we can advise them on where to buy animals or not, how to properly quarantine, and what vaccinations to give.”

– MoA Key System Owner

Decisions Enabled

When quality data flows across the value chain and livestock data systems are interoperable, well-informed decisions can be made to improve livestock across Ethiopia. Effective decisions can be made on matters such as vaccine rollouts, trade and export policies, disease control, and traceability.

“One of the issues as a leader is that I have to go to each system owner for the data I need. When it is made interoperable, I can access all the data and the systems should feed into each other.

“As a leader, if I have the five data sets in one click, it helps me to respond to diseases; it helps me to really check whether the bulls are appropriately selected; and it helps me to also know the average price of livestock or cattle, sheep, and goats.”

– Dr. Fikru, State Minister for Livestock

Here are a few key examples:

In order to decide where and when to launch vaccination campaigns, decision-makers can make use of interoperable data in the Livestock Information System (LIS), drawing from the Ethiopian Livestock Identification & Traceability System (ET-LITS), Animal Disease Notification & Investigation System (ADNIS), and Disease Occurrence & Vaccination Activity Reporting (DOVAR) system. By making interoperable animal movement data from ET-LITS and outbreak data from ADNIS & DOVAR, decision-makers can anticipate where livestock are at risk and proactively deploy vaccines and treatment services.

Another goal that policymakers could work towards through data-driven decision-making is the improvement of bovine breeding programs. Using the genetics database from artificial insemination (AI) service records and production data from LIS, decision-makers can determine which bulls and sires to prioritize and where to expand AI services. Performance data from LIS helps these decision-makers identify high-yield or climate-resilient traits. This informs the selection of sires and helps guide the targeted rollout of AI in specific production systems.

“Imagine if the information, the data that we have about a given bull is wrong when making breeding decisions. I’m spoiling the whole generation, the whole herd, the coming generation, and the productivity at the farm level, which, at the end of the day, gives us the wrong efficiency for milk production. So accurate data is very critical.”

– Dr. Fikru, State Minister for Livestock

A final example is of policymakers using data-driven decisions to improve export market readiness. Data from ET-LITS and the National Livestock Market Information System (NLMIS), including export data, can inform policymakers on how to improve compliance with international traceability and food safety standards. Using LIS, decision-makers have access to individual animal-level traceability linked to animal profile – including breed, age, etc., health records, and abattoir data. This enables Ethiopian policymakers to set standards that help producers meet certification requirements for premium markets, such as the United Arab Emirates (UAE) and European Union (EU); set pricing and grading, and determine trade volume.

“The decision of the countries that import the majority of our livestock on whether or not to do so is based on disease information. We need to show strong traceability and transparency to our trading partners. If we don’t have the data, our trading partners won’t trust us.”

– MoA Key System Owner

Farm-Level Impact

Given that aLIVE works at the government level, the focus is often on the use of data for policymaking and the national impact of the livestock sector. What sometimes goes unsaid, though, is why and how these policies can have a national impact, which is partially attributed to the implications that these policies can have at the farm level. The positive impact of properly informed decision-making on producers can be further enhanced by providing access to data and interpretation skills to farmers and the private sector.

Informed decision-making regarding livestock has positive direct and indirect impacts on producers, including farmers, abattoirs, and the private sector. Improved traceability resulting in expanded access to markets and financial inclusion, system upgrades, new data visualizations, and strengthened data sharing benefit actors across this chain. A strong livestock policy can better engage farmers and other producers as informed contributors to the sector, rather than passive participants.

“The problem in our country is we force farmers to report and send their data, but they don’t get use out of it.”

– MoA Key System Owner

Establishing a data feedback loop empowers them to consider not only immediate choices at the household level but to make calculated decisions that improve animal health and access to markets, improving long-term gains for themselves and for Ethiopia.

“The data will help the farmers. Currently, our data systems are not accessible to farmers, but they benefit from feedback mechanisms from top to bottom levels. If these feedback systems are based on the right information, then we can put in place the right interventions, and these interventions will benefit the farmers. It’s important to provide real-time interventions for real-time problems.”

– MoA Key System Owner

For example, setting stringent standards at the policy level helps farmers produce accordingly so that they have better access to trade. A strong LITS system, along with farmers who are incentivized by the benefits of contributing data, enables expanded and reliable access to international markets by meeting traceability requirements abroad. Robust livestock health and genetics data systems enable decision-makers to introduce targeted health interventions, such as vaccines, and breeding programs that improve livestock outcomes at the farm level. These tangible results demonstrate to farmers the advantages of providing data to the government, and this cycle once again benefits government decision-makers, the livestock sector, and even Ethiopia broadly.

Conclusion

Effective decision-making in the livestock sector depends not just on having the right data, but on ensuring that data flows meaningfully across every level of the value chain – from farmers to policymakers and back again. The aLIVE program demonstrates how a well-connected, interoperable data system – supported by trained data users, clear visualizations, and a feedback loop that includes all stakeholders – can unlock evidence-based and timely decisions that benefit Ethiopia from the national economy to individual farmers.

“Currently, if I need relevant market information, I have to go to MoTRI and ask for it. But if we have one dashboard, with a single click I can understand what’s going on with livestock trade and breeding. aLIVE is making interoperable all of this fragmented data. Decision makers don’t have time to go to each system without summarised information in a single dashboard. With it, it will be easy for them to make the right decisions.”

– MoA Key System Owner

Viewing decision-making as a process informed by various actors, institutions, systems, and sectors, aLIVE’s successful approaches reinforce that headway is made when data doesn’t sit in silos but moves fluidly. Bridging levels of the livestock value chain means that this data can properly inform vaccine campaigns, breeding programs, trade policy, and on-farm decisions. When system owners are empowered to use and share data effectively, policymakers have timely and comprehensible insights, and farmers are engaged as contributors, users, and beneficiaries of data, the impact is more penetrative, equitable, and sustainable.

“One of the issues as a leader is that I have to go to each system owner for the data I need. When it is made interoperable, I can access all the data and the systems should feed into each other.”

– Dr. Fikru, State Minister for Livestock

We believe that a resilient livestock sector is one founded upon decisions which are evidence-based, inclusive, and aligned from the ground to the national level and across institutions. As this blog series will continue to explore, visualization, learning exchanges, and localization are key enablers that make this kind of decision-making culture possible and lasting.