Incentives and Opportunities for Alignment with Country Systems

Last month, we explored opportunities for better resourcing for the data revolution – and found that calls for greater coordination particularly resonated. Amongst development providers, there’s concern about duplication of efforts – particularly in a political context of decreasing budgets and increasing scrutiny for aid.

This interest in coordination should not be surprising – provider countries have endorsed principles of harmonization as part of the aid effectiveness agenda, signaling this as a core need. However, this apparent lack of coordination is also concerning in that it suggests we have failed to live up to the commitments made in Paris, Accra, and Busan around country ownership and harmonization.

No, and yes. At the last OECD Results Community meeting, participants agreed that country partner frameworks should be at the heart of providers’ priorities. Further, since the launch of the aid effectiveness agenda, partners have noted an increase in appetite from country partner governments to lead cooperation processes. Such work has been facilitated through technological aid information management systems, and through strong country-level sectoral working groups (that are harmonizing, and not extractive).

However, today’s global development landscape poses unique challenges. In particular, heightened scrutiny around public financial management – and increased expectations around accountability for results – can complicate providers’ alignment with country systems.

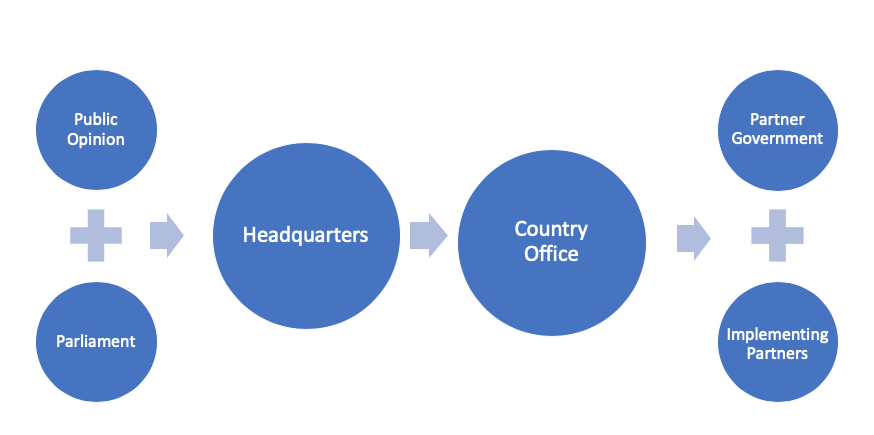

The network of actors that influence provider agendas and alignment include:

The amount of alignment with country systems – such as national monitoring and evaluation (M&E) or results frameworks, strategies, and data systems – falls on a spectrum:

- Some providers, such as Denmark and Sweden, may align completely with partner government frameworks, in line with aid effectiveness principles;

- Some, such as Belgium and Switzerland may align with partner government frameworks, with the addition of a “menu” of corporate indicators for reporting purposes; and

- Some, such as the US, may have little or no alignment – particularly if implementing partners are civil society organizations.

Reasons for this spectrum vary – but can often be traced back to three key drivers:

1. Public trust and buy-in to international assistance as a principle, versus demands for financial and results-based accountability.

This often depends on provider country context and politics. For example, it has been found that Scandinavians tend to be more supportive of international assistance as a normative good, while other populations may link international assistance with national security or business priorities.

2. Timeliness of partner country data, particularly in fragile states.

Some providers support statistical and administrative data capacity. However, if country system data quality and timeliness are at issue, provider reporting obligations may incentivize third-party data collection.

3. The complex “constellation” of providers and partners within a country.

In addition to civil society partners, there may be multiple government aid agencies operating in-country – complicating provider-national alignment, let alone alignment across different national providers.

How do we address these ongoing coordination challenges? One major step forward would be bringing the results and aid effectiveness agendas into greater harmony, as reinforced by the Sustainable Development Goal 17 call for stronger development partnerships. Within development partners, this goal could be advanced by increasing institutional focus on learning; some partners identified “rebranding” M&E to MEL (monitoring, evaluation, and learning) as an achievable starting point.

But a more challenging – and more rewarding, if successful – approach within development partners would be to bridge the”missing middle” that often exists between corporate and project/program level results data. Further, we could also stand to get more comfortable with the contribution versus attribution debate: specifically, with aid agencies contributing to national development outcomes (and understanding what mechanisms were most effective), rather than aiming to attribute each taxpayer dollar to a specific output.

Being able to better analyze and understand portfolio – sector or country-wide – results, and reducing the primacy of project-level results, can lead to greater coordination, through strengthening and use of country systems to evaluate success.

Thumbnail image: The Global Goals for Sustainable Development

Share This Post

Related from our library

Economic Toll of Tobacco-Related Diseases in Kenya: New Research Findings

Development Gateway: An IREX Venture (DG) is pleased to announce the publication of a research manuscript on the Economic Costs of Tobacco-Related Illnesses in Kenya. This research was carried out as part of the Tobacco Control Data Initiative (TCDI) activities in Kenya and is part of a broader report on Morbidity and Mortality from Tobacco Use in Kenya.

Building a Sustainable Cashew Sector in West Africa Through Data and Collaboration

Cashew-IN project came to an end in August 2024 after four years of working with government agencies, producers, traders, processors, and development partners in the five implementing countries to co-create an online tool aimed to inform, support, promote, and strengthen Africa’s cashew industry. This blog outlines some of the key project highlights, including some of the challenges we faced, lessons learned, success stories, and identified opportunities for a more competitive cashew sector in West Africa.

Digital Transformation for Public Value: Development Gateway’s Insights from Agriculture & Open Contracting

In today’s fast-evolving world, governments and public organizations are under more pressure than ever before to deliver efficient, transparent services that align with public expectations. In this blog, we delve into the key concepts behind digital transformation and how it can enhance public value by promoting transparency, informing policy, and supporting evidence-based decision-making.