Incentivizing Data Quality and Use

Miss the earlier posts in this series? Check out the first and second post before reading more.

|

“If we say an issue is a big challenge, that must be backed up by information. We strive to base everything we put in [strategies and plans] on tangible data.” – Interviewee |

Data-driven decision-making was considered a positive norm across countries researched during the UNICEF Data for Children pilot process. Ideally, the national data use cycle would consist of:

(i) evidence-based planning;

(ii) implementing programs according to plans;

(iii) monitoring and evaluation (M&E) and reporting;

(iv) analyzing data; and

(v) making appropriate planning or program adjustments.

However, the extent to which government data were used beyond planning – for measuring progress, making course-corrections, and determining “what works” – varied. We found much of this variation could be explained by the degree to which results data were used for accountability over learning; and the extent to which data were proactively shared.

Getting to Accountability for Results

Results frameworks send an important signal regarding the government’s priority outcomes, and help establish accountabilities for achieving those outcomes. The lack of a framework – or its limited scope, particularly in devolved governance contexts – hinders the ability to measure progress and evaluate the effectiveness of interventions.

We’ve written before about how results (M&E) data can be used as a vehicle for strengthening country systems. Results-based financing programs that use administrative data as a disbursement trigger and verification mechanism can incentivize, and financially support, greater data quality.

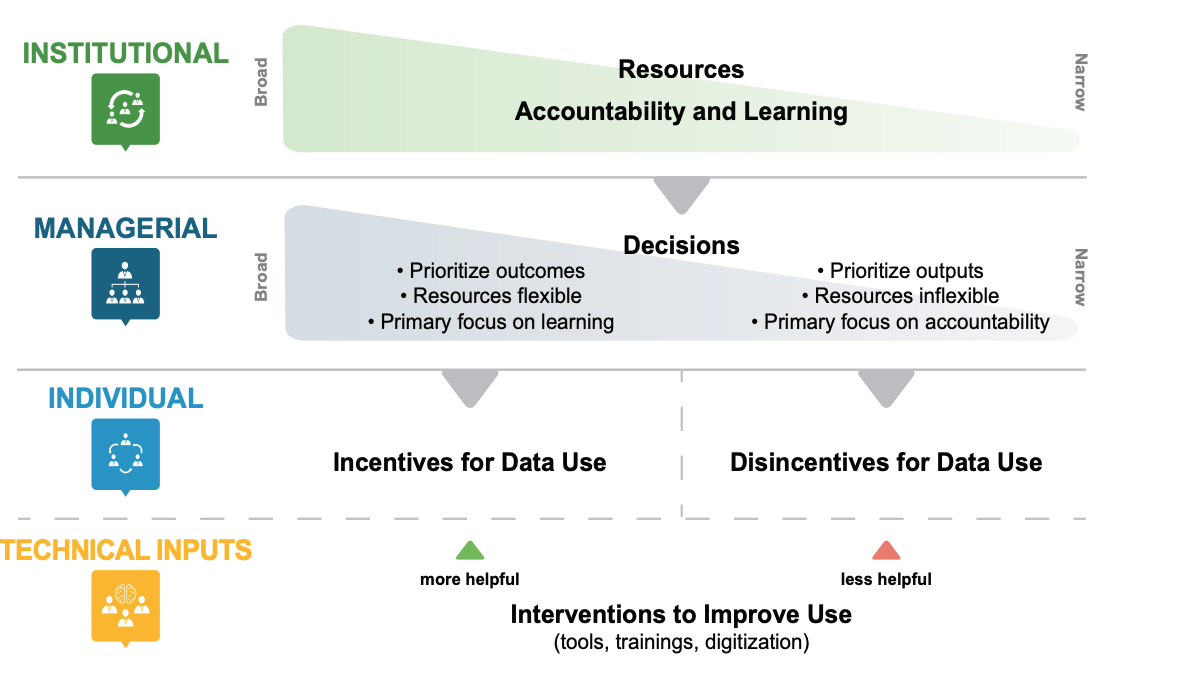

Figure 1: Understanding Decision Space

But we also argue that the inverse is true: if data systems are not used for meaningful accountability purposes – budget justifications, achievement reporting, or even generally made available for media and civil society – there is less incentive to invest resources needed to ensure data accuracy.

|

An example of the power – and pitfalls – of data for accountability is public financial management (PFM) reform. Across countries of research, development partners had focused on, funded, and incentivized PFM reform; and governments responded by putting in place processes, legal frameworks, and data systems to ensure financial compliance. This indicates the power of scrutiny as a lever for policy change and investment. But this also underscores the risk of financial accountability crowding out a focus on accountability for development outcomes. In countries of research, legislatures, ministries of finance, and departments of budget had far more legal, financial, and human resources at their disposal to carry out their mandates, than did national statistical offices, planning commissions, or ministry M&E departments. |

The Complexities of Data Sharing

Further constraining data use – and contributing to the fragmentation of investments in data – are poor data sharing practices. The robustness of data sharing between government and the public through freedom of information laws correlates with government accountability and trust, and is the subject of much advocacy. But arguably less well-known are the significant challenges to data sharing within, and between, government agencies.

Why? Within the National Statistical System (NSS), data sharing challenges often related to overlapping policy frameworks. Typically, legislation establishing the National Statistical Office’s mandate would be followed years later by separate legislation outlining responsibilities of line ministries in collecting service delivery data. The lack of policy harmonization often contributed to fragmented or incomplete responsibilities regarding data processing and sharing.

Data sharing was also hindered by concerns about data privacy, and an incomplete understanding of good practices related to anonymization and ethical sharing. This was particularly a challenge for non-custodial ministries – such as Ministries of Women and Children’s Affairs – that relied on data from other agencies (health, education, justice) to carry out monitoring and advisory mandates.

Limited data sharing not only harms accountability and trust: it can also contribute to fragmented systems, investments, and inefficiencies across programs. One example of this fragmentation emerged in the education sector in the Philippines. Legally, service provision and oversight is divided between the Early Childhood Care and Development (ECCD) Council, responsible for managing daycare, preschool institutions, and conditional cash transfer programs; and the Department of Education, responsible for managing primary and secondary education programs.

Both the ECCD Council and Department of Education use separate information systems to monitor students and programs – but regularly sharing data between systems is beyond the mandate of either entity. As a result, it can be difficult to detect instances of delayed primary school enrollment, and has repercussions across enrollment-related school programs. An example of this was identified in the Mindanao region of the Philippines, where cross-referencing between education and social protection data systems identified thousands of “ghost” students improperly receiving social transfers.

Ultimately, data quality and use are functions of each other. Both are influenced by the accountabilities and incentives of data demanders and producers – because at heart, data are political. So how can we use this knowledge to drive better outcomes? Stay tuned for our final post, exploring opportunities within national data ecosystems.

Over the past two years, Development Gateway (DG) worked across seven countries and two regions to support the roll-out of UNICEF’s Data for Children Strategic Framework. This work included developing country ecosystem diagnostics and strategic action plans for UNICEF Country Offices in Myanmar, Papua New Guinea, Philippines, Thailand, Viet Nam, Lesotho, and Ethiopia; and for the UNICEF East Asia and Pacific Regional Office. Development Gateway holds long-term agreement with UNICEF to continue this work around the world.

Share This Post

Related from our library

Development Gateway Collaborates with 50×2030 Initiative on Data Use in Agriculture

Development Gateway announces the launch of the Data Interoperability and Governance program to collaborate with the 50x2030 initiative on data use in agriculture in Senegal for evidence-based policymaking.

Reflecting on 3 Years of Digital Advisory Support for Agricultural Transformation

As the DAS program concludes, this blog reflects on its impact in advancing digital transformation in agriculture, highlighting lessons on capacity building, knowledge transfer, and sustaining resilient food systems.

From Data to Impact: Why Data Visualization Matters in Agriculture

This blog explores why data alone isn’t enough; what matters is turning it into usable insights. In agriculture, where decisions have lasting impacts, user-friendly tools help farmers and policymakers alike make better choices.