The Geocoding Suite: Let’s Get Technical

Development Gateway’s Geocoding Suite has several components, each working in tandem with aid and management information systems to assign precise geospatial data on the locations of development projects.We have recently announced the addition of a lightweight, user-friendly automatic geocoding backend tool – aptly called the AutoGeocoder. If you read our last blog post, you’re familiar with some of its highlights, functions, and features. In today’s post, we’ll be diving deeper into the tool’s inner workings – as well as into recent changes we’ve made to the lightweight, open source Open Aid Geocoder tool.

Below, we begin with the AutoGeocoder:

AutoGeocoder

As mentioned in our last post, the AutoGeocoder tool reads through text provided in various document formats (PDF, DOC, TXT) to identify activity locations, and then produces a final list of georeferenced location names. The tool has been fully developed in Python 3, and combines well-known tools and libraries such as NLTK and scikit-learn.

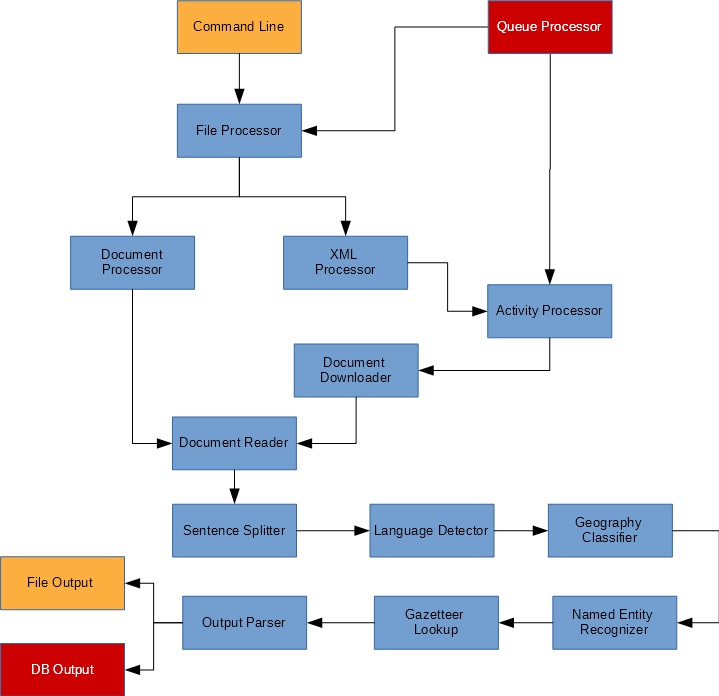

In short, the AutoGeocoder is able to read a text-based document, split it into sentences, classify those sentences using a text classifier, filter classified sentences to include only project implementation-related text, generate a list of named entities from the selected sentences by querying the Stanford NER Server, and finally query the GeoNames API to retrieve the final project location information.

It is composed of three key elements:

- A supervised machine learning-based text classifier that detects which sections of the documents refer specifically to project implementation details;

- A Named Entity Recognizer (NER), currently provided by Stanford NER;

- A Gazetteer Service, allowing the tool to query geographic information, provided by GeoNames.

The AutoGeocoder can be configured to run in three different modes:

- Firstly, it can be run through the command line interface – which is the tool’s default mode. This mode is useful in extracting project locations from single text documents or from IATI XML files.

- With a bit more configuration, and setup of a PostgreSQL database, the user can interact with the tool through the Micro Web user interface. This allows users to upload files, autogeocode them, download the results, and track all sentences that were used as location sources.

- Finally, plugging the AutoGeocoder into the current Open Aid Geocoder database allows the user to send previously-imported activity records to the AutoGeocoder process queue, see which projects have already been autogecoded, review locations on the map, and manually edit information.

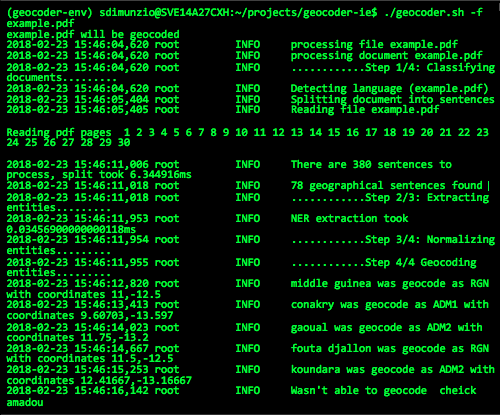

Figure 1: the AutoGeocoder Command Line Interface – Geocoding a PDF file

Figure 2: AutoGeocoder Full Process Workflow

Machine Learning

As mentioned, a key piece of the AutoGeocoder is the pre-trained text classifier. Using machine learning, it tells the tool whether a found location is actually the project implementation location or is an irrelevant location (such as the address of the donor’s headquarters). The default classifier has been trained with a small dataset, so it is recommended that users train their own text classifiers to achieve enhanced precision.

The AutoGeocoder provides a set of features useful for this task:

- An IATI data downloader;

- A text sample generator method, which can be called from the command line tool;

- A n interface to manually classify text samples.

- A classifier trainer method – which generates a ready-to-use classifier that can be called from the command line tool.

For further assistance in preparing a classifier, please see at the installation guide here. Additionally, please find the Autogeocoder Github repository here.

Open Aid Geocoder

Another recently-updated Geocoding Suite feature is the Open Aid Geocoder. Originally, this tool was designed to be plugged into an existing IMS system, but in keeping pace with user demand, we have created an API and simple database for the interface – allowing it to run as a standalone service. As mentioned in our last post, it now also uses the AutoGeocoder as well as allows for manual searching and adding of location information.

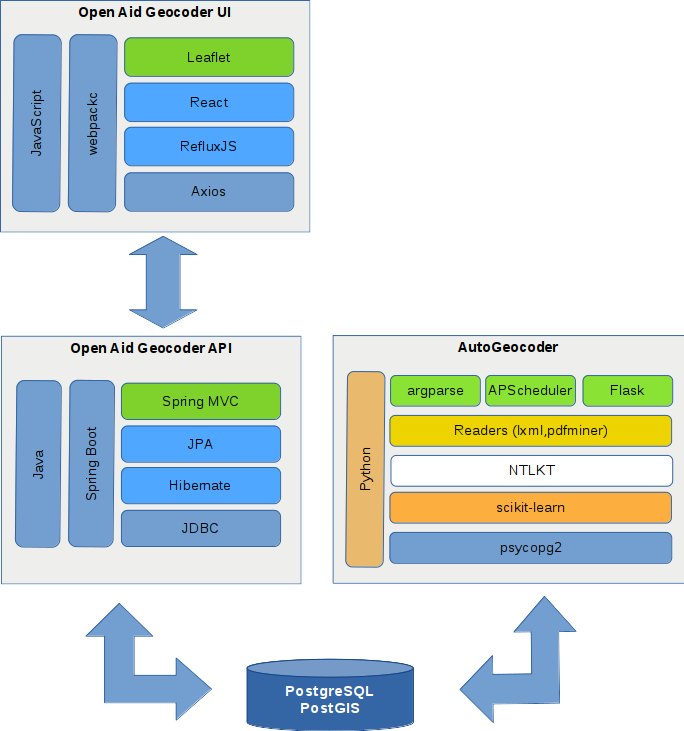

The Open Aid Geocoder, is now composed of two main modules – the Geocoder API and the Geocoder UI:

Geocoder API

Entirely developed in Java and based on the Spring framework, this RESTful API provides the UI with backend support. The Geocoder API exposes a group of JSON HTTP endpoints, which allows the UI to import new project records, read the current list of projects, read full project information by providing a project identifier, and save edited records. The PostgreSQL database and the PostGIS extension store geographic project information as well as Global Administrative Boundaries (GADM) records. These records allow the UI to render the project’s recipient country administrative boundary layer over the map, and then query administrative names while manually geocoding. We’ve developed the API to provide a default backend to the Open Aid Geocoder, allowing seamless usage of the tool as a standalone web service. For a better look at the Geocoder API, check out the Github repository here.

Geocoder UI

The Geocoder User Interface (UI) has been built using the latest innovative technologies, such as React and Reflux, mixed with other popular libraries such as Leaflet, i18next and Bootstrap, compiled together using Webpack. As the Geocoder UI is a purely Javascript application, it can be integrated into any existing web-based system.

Originally released last year, the Geocoder UI has undergone a major refactoring to adapt to the recently-developed Geocoder API. We’ve also added new capabilities such as multilingual data entry support, integration with the AutoGeocoder, Import/Export of IATI 2.01 and 2.02 XML files, and a renewed, freshly designed interface. For a better look at the Geocoder UI, see the corresponding github repository here, and take a look at the User Guide here.

Figure 3: Geocoder Suite Stack Diagram

Figure 4: Elements of the AutoGeocoder

The Development Gateway Geocoder Suite project team includes: Mauricio Bertoli, Anush Martirosyan, Ionut Dobre, Taryn Davis, Sebastian Dimunzio, Galina Kalvatcheva, and Llanco Talamantes.

Share This Post

Related from our library

Introducing The HackCorruption Civic Tech Tools Repository

Introducing the Civic Tech Tools Repository: an open-source hub of digital solutions to fight corruption. Designed for growth through GitHub contributions, it brings together tools, code, and resources across six key areas for HackCorruption teams and beyond.

Building a Sustainable Cashew Sector in West Africa Through Data and Collaboration

Cashew-IN project came to an end in August 2024 after four years of working with government agencies, producers, traders, processors, and development partners in the five implementing countries to co-create an online tool aimed to inform, support, promote, and strengthen Africa’s cashew industry. This blog outlines some of the key project highlights, including some of the challenges we faced, lessons learned, success stories, and identified opportunities for a more competitive cashew sector in West Africa.

Digital Transformation for Public Value: Development Gateway’s Insights from Agriculture & Open Contracting

In today’s fast-evolving world, governments and public organizations are under more pressure than ever before to deliver efficient, transparent services that align with public expectations. In this blog, we delve into the key concepts behind digital transformation and how it can enhance public value by promoting transparency, informing policy, and supporting evidence-based decision-making.