New Research Reveals Reasons for Shisha Smoking in Nigeria

Today, we’re excited to announce our Tobacco Control Data Initiative (TCDI) published groundbreaking research shedding light on reasons for shisha smoking across Nigeria. The research paper, “Reasons for shisha smoking: findings from a mixed methods study among adult shisha smokers in Nigeria,” was published by PLOS Global Public Health and provides vital context-specific evidence to inform the national response to increased shisha smoking. This study, the first of its kind to be conducted in Nigeria, used a mixed methods approach and covered all geographical regions of Nigeria. It was produced in partnership with R-DATS consulting and funded by the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation.

Key Findings

The research, led by Dr. Noreen Dadirai Mdege, comprises in-depth interviews with 78 current shisha users in 13 states, along with a quantitative survey involving 611 current shisha users across 12 states, spanning Nigeria’s six geopolitical zones.

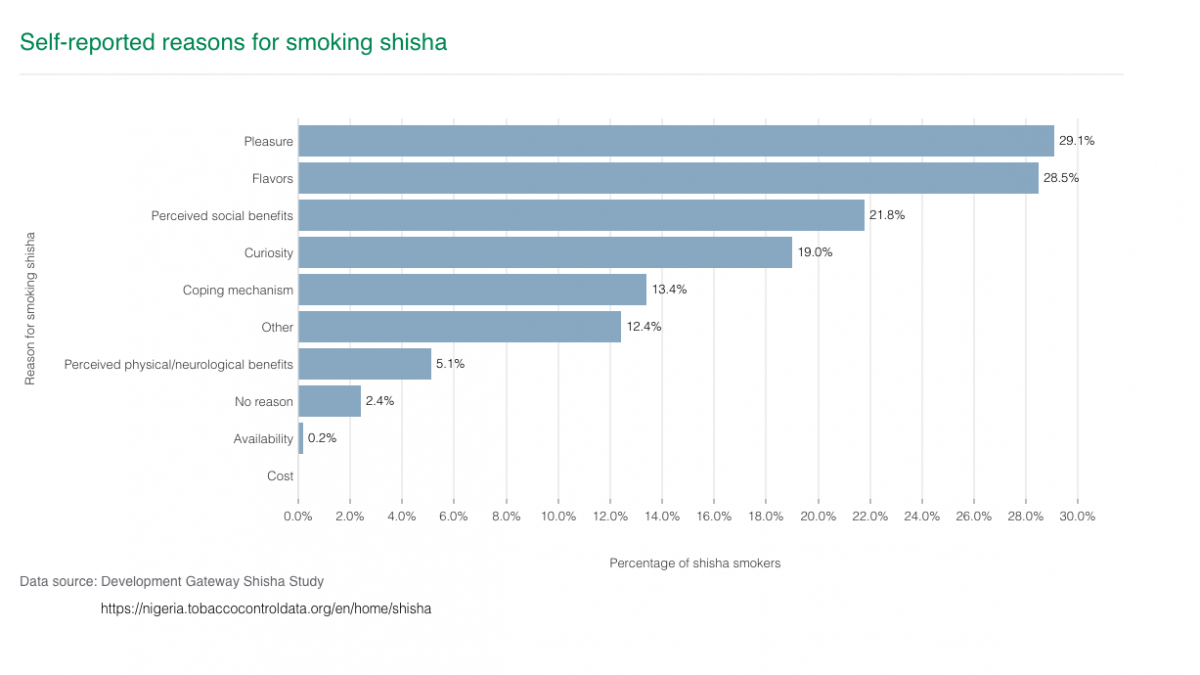

One of the most common, self-reported reasons for smoking shisha was shisha flavors. Shisha came in a variety of flavors that made people want to try or continue smoking it, and also gave both smokers and non-smokers the impression that shisha is safe, or safer than cigarettes. In addition, shisha smoking was also driven by curiosity about other product attributes such as the smoke; beliefs that it was helpful for coping with challenging life situations such as stress, sadness or joblessness; limited knowledge on the negative health effects; the availability of and ability to smoke shisha in many places, including places where cigarette smoking is prohibited; and poor enforcement and compliance monitoring of the existing tobacco control laws. The presence of friends and family members who smoke shisha, coupled with the need to belong during social events, also played a significant role in promoting shisha smoking.

On the other hand, negative societal views towards shisha smoking and the high costs of shisha discouraged people from smoking it. Additionally, the research indicates that quitting shisha smoking without support is a challenging endeavor.

Implications for public health

This study makes a significant contribution to evidence for decision-making in regards to public health. Restrictions on flavors, strengthening compliance monitoring and enforcement of the tobacco control laws in relation to shisha (e.g., smoke-free environments in indoor and outdoor public places; having health warnings in English on shisha products; and tax measures) have the potential to minimize initiation and use, and to protect the health and wellbeing of Nigeria’s general public.

Dr. Mdege states, “We conducted this study as a response to an expressed need from the tobacco control community in Nigeria for data to inform policy-decisions on how to tackle the alarming surge in shisha smoking. We, therefore, hope that this research and the underlying data will contribute to strengthening tobacco control efforts in Nigeria as well as in other similar contexts.”

The full research paper is available here at PLOS Global Public Health. Access our tobacco control data for Nigeria here.

Share

Recent Posts

Supporting Ethiopia’s National Soil Fertility and Health Action Plan

Declining soil fertility remains a major constraint on Ethiopia’s agricultural productivity. This blog reflects on the launch of the National Soil Fertility and Health Roadmap and DG’s support in its development, highlighting lessons on government-led reform and long-term resilience.

Development Gateway Collaborates with 50×2030 Initiative on Data Use in Agriculture

Development Gateway announces the launch of the Data Interoperability and Governance program to collaborate with the 50x2030 initiative on data use in agriculture in Senegal for evidence-based policymaking.

Strengthening Online Safety Through Prevention in the Philippines

Tech-Facilitated Gender-Based Violence continues to evolve alongside emerging technologies. This blog explores how preventative measures, such as the Safety By Design approach, can be used to create a safer internet.

Democratizing Digital or Digitizing Democracy?

The 2023 OGP Summit in Tallinn, Estonia featured a number of discussions centered on open government in the digital age. While the use of digital tools in government is far from a new idea, the COVID-19 pandemic spurred a rapid expansion of this practice, with leaders quickly adapting to remote environments through digitizing government processes and services. As countries around the world recover from the impacts of the pandemic, the continued intersection of digital technology with democratic processes seems inevitable. The Summit highlighted a definition of digital democracy where democracy itself is furthered through the use of digital tools and technology, as is the case in Estonia. Estonia’s leadership in government e-services – e-Estonia– is well known: government services such as legislation, voting, education, justice, health care, banking, taxes, policing, etc. are digitally linked. This is an introduction of democracy and governance through digital.

With online platforms and tools, digital democracy has the potential to make critical information open and accessible, facilitate open dialogue, and streamline decision-making processes. It fosters inclusivity, allowing individuals from diverse backgrounds to voice their opinions, engage in policy discussions, and even play a direct role in shaping the policies that affect their lives. However, as with any innovation, digital democracy comes with its share of challenges, including issues related to privacy, misinformation, targeted harassment and violence, and reinforcing unequal access to democracy and justice due to the digital divide. To create more equal benefits, and mitigate critical risks, USAID, the US State Department, and others through the Summit for Democracy are focused on embedding democratic values and human rights into tech development, design, and deployment. This is democracy in digital.

Both democracy in digital and democracy through digital are required for building resilient, effective, and trusted institutions. As our world becomes increasingly interconnected, understanding and harnessing the potential of digital democracy becomes essential for creating more responsive, transparent, and accountable governance systems.

Improved transparency and accountability: Open data and transparency in government processes allow civil society and the public to track decision-making, policy formulation, and spending. Governments collect a massive amount of data and open government policies, such as open data, have great capacity to increase public trust.

Still, just because data exists does not mean people have access to it in a way that is usable for them. Ensuring data is user-friendly and accessible goes beyond standard user design principles, but acknowledges the importance of sharing information in accessible formats. This takes understanding distinct relationships between different stakeholders – how governments communicate to the public, how civil society engages with government – and responding in kind. DG’s Open Contracting Portal, which was designated as a Digital Public Good last year, is an example of an open source tool built with government processes, including engagement with citizens, at the center. Launched in Makueni County, Kenya, the Open Contracting Explorer has been scaled to other counties in Kenya, including a current partnership with Nandi County.

We often find that digital tools and projects, especially at the pilot or proof of concept stage, are developed with one specific user group in mind (such as government or civil society). When only one group is being well-served by a tool, its use is severely limited. Concurrently, we see anti-corruption and transparency tools designed based on what data or information is already available, not on what is needed by distinct, diverse users. Intentional collaboration from multiple groups is key to developing the best possible tool for a given country or context.

Inclusivity and accessibility: One of the core benefits of an increasingly digital democratic process is the potential to make civic participation more inclusive by breaking down long-standing barriers like physical location, mobility, gender norms, and time constraints. Some important components of democratic governance like community meetings and whistleblowing have moved online. Where populations are connected, this expands access exponentially – people who don’t have reliable access to transportation, people with children, young people and others who might not have the time or capacity to travel to in-person meetings can contribute to discussions and engage in the governance process. Online platforms can enable people from all walks of life to engage in discussions, share their opinions, and take part in decision-making processes. In addition, digital tools like social media can facilitate direct interaction between people and their government representatives, fostering a closer connection and increasing citizens’ sense of participation in government.

However, this direct interaction comes with its own share of risks, for example the targeted harassment and intimidation of women participating in politics and public life. Technology facilitated gender-based violence (TFGBV) is a growing problem, and too often plays a role in forcing women out of public life to preserve their mental and physical well-being. A thriving digital democracy must find ways to support improved gender representation and participation, and innovative approaches to combat TFGBV – like those being researched and piloted by IREX in its USAID-funded Transform activity – are needed to live up to this ideal.

While discussing the major opportunities for inclusivity with digital democracy, it is equally important to acknowledge the digital divide – the gap between those who have access to digital tools and the internet and those who do not. Many people, even in the richest countries in the world, do not have reliable access to the internet. Beyond this, effective participation in digital democracy requires a certain level of digital literacy and there are many groups who are less likely, or less able, to engage online due to a lack of comfort with or equitable access to digital tools. As governance processes move online, leaders must remain cognizant of the digital divide and consider a hybrid approach that takes multiple participatory mechanisms in account, and pursue investment in education and training to empower people in navigating online platforms responsibly.

Further, respect for human rights and democratic values must be embedded directly into the design of digital solutions. Democratic values should be included within the development of solutions themselves. This includes elements like respect for privacy, protecting data about vulnerable people, and combating misinformation. It also includes intentionally designing for marginalized communities to prevent furthering the digital divide.

e-Estonia is a remarkable goal and the progress towards digital democracy is clear; but the population (1.3 million) represents a relatively small-scale example when compared, for example, to Nairobi County in Kenya, with four times Estonia’s population. The e-Estonia roadmap or the Estonian X-Road source code cannot be copy-pasted into societies around the world to drive digital democracy, but countries can pull lessons from this important work. Rights-respecting principles, inclusion of civil society in digital processes, and the development of stronger values-based regulatory frameworks for digital are key components for driving progress in digital democracy.

And while the promise of cutting-edge technology to improve governance is tantalizing, the immediate focus of digital transformation should be to establish best practices for applying sustainable, ethical approaches to the use of data and digital technology at the outset. True digital transformation requires policies and approaches that support digitization of democratic processes in a user-friendly, equitable, and sustainable format. And ultimately, all digital technology should be developed and implemented with the utmost respect for human rights and democratic values.