The State of Data in DG’s Work

Three years ago, as we were preparing our new DG organizational strategy, we decided on a significant shift: after more than 15 years functioning as a “generalist” organization, with some specialization in public financial management (PFM), but no sector focus, we identified a set of sectors on which to focus our work. Narrowing our work presented a tradeoff, between keeping ourselves open to all opportunities and beginning to develop deeper partnerships and expertise in a prioritized set of topics.

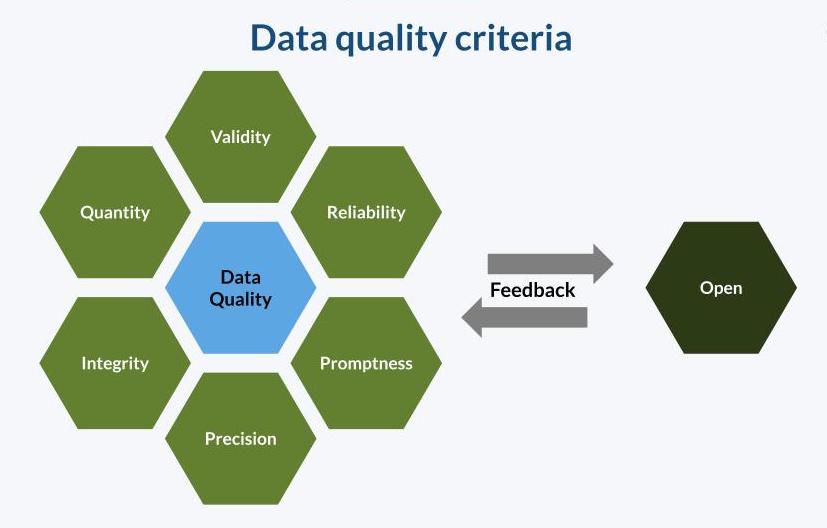

Over the coming months, we will be refreshing our strategy and refining our approach within our priority sectors. As we review our strategy, we plan to share here much of what we’ve learned through programming in more than a dozen countries – from our work and from our excellent partners – about the state of data in agriculture, tobacco control, open contracting, and the extractive industries. For each theme, we’ll explore who are the key data users, the decisions they make, the most important data gaps, and the crucial risks of data (mis)use. Below are previews from some of our flagship programs.

Agriculture: Bridging Public and Private Sector Needs

Data in the agriculture sector are highly fragmented, collected by both public and private sector, and too rarely shared effectively in a timely and harmonized way. DG’s work in fertilizer – together with the International Fertilizer Development Center and The African Fertilizer and Agribusiness Partnership – and seeds systems – together with The African Seed Access Index – has focused on bringing these disparate strands of data into meaningful analyses of agricultural inputs. Key data gaps in agriculture center on retail-level (e.g agro-dealer) information, as well as disaggregation of data by gender. Data governance challenges include 1.) identifying ways for private sector data to be shared and reused while protecting commercial confidentiality, 2.) and generating subnational data while preserving land – and other – rights of smallholder farmers.

Tobacco Control: Providing Data Users Can Trust

Tobacco Control data suffer from a similar dispersion as agriculture, although differ in one key characteristic: the perceived reliability and impartiality of data sources. The tobacco industry has invested heavily in generating its own data and evidence – ranging from support for new products like electronic nicotine devices (ENDs, or more commonly eCigarettes) to touting the economic benefits of tobacco farming – to discourage tobacco control legislation and enforcement. Governments, and their civil society counterparts, need access to a trusted source of data on key areas including: tobacco prevalence, use of new and alternative tobacco products (e.g. ENDs, shisha), economic and health impacts of tobacco use, and revenue impacts of excise and other taxes, among others. Finding these data, vetting sources, filling gaps, and presenting data in a validated and trusted manner all present their own unique challenges. Finally, capturing new data to fill gaps often calls for household surveys and other individual-level collection of sensitive data, requiring strict measures to collect data ethically and protect it effectively.

Open Contracting (OC): Getting to Impact

Each year, governments spend approximately $13 trillion through public procurement – 97% of this spending is not transparent or open to the public who fund government budgets. Governments themselves often lack the tools and analytics to assess how effective they are in spending public resources, as they seek to save money and efficiently procure services. DG’s support to governments from Chile to Makueni County, Kenya has helped to improve their procurement processes, saving time and money. The key gaps moving forward are improving government and civil society capabilities to assess the impact of improved procurement on service delivery – an area where DG is partnering with Hivos and the government of Makueni County – and the ability to perform more sophisticated analysis on pricing and competitiveness. Still, far too much procurement data live on paper, and there are significant gains to be made from continued digitization and standardization. Linking open contracting with beneficial ownership, while considering commercial confidentiality and individual privacy concerns, is a further frontier issue for OC data governance.

Extractives: Reversing the Flow

For nearly 20 years, the Extractives Industry Transparency Initiative (EITI) has called for and supported greater transparency from national governments and private companies on the deals and dollars of the extractives sectors. However, the flow of these data have been primarily oriented toward global transparency and reporting, while we have identified significant unmet needs for timely, transparent, and actionable data at the country level. Developing better local tools for data aggregation, standardization, reporting, and analysis has the potential to significantly improve the impact of EITI and EI data for decision-making. Additionally, evaluating the needs of women’s and indigenous groups – and weighing them more evenly with powerful constituencies within government and private sector – requires a rethinking of the extractives transparency movement to ensure that these resources are benefiting the communities from whom they are being extracted.

Moving Forward

While we have made strong contributions within each of the spaces above, we recognize just how much we still need to learn. As we share our reflections, we will also be reaching out to various partners, funders, and experts within each to see what we are missing, and inform our next steps in our refreshed strategy.

Photo credit (clockwise from top left): Vinisha Bhatia-Murdach, Ayotunde Oguntoyinbo, Robina Weermeijer, Taryn Davis

Share

Related Posts

The Cancer-Tobacco Link: Using Data to Drive Stronger Tobacco Control Policies

As we observe World Cancer Day today, it is crucial to recognize the significant role smoking plays in the global cancer epidemic. Tobacco use is the leading preventable cause of cancer and cancer-related deaths worldwide, necessitating a dynamic, multidisciplinary approach to tobacco control interventions. DG’s Tobacco Control Data Initiative (TCDI) contains country-specific websites designed to

How Useful Is AI for Development? Three Key Lessons

The development world is buzzing with excitement over the idea that new and emerging applications of AI can supercharge economic growth, accelerate climate change mitigation, reduce inequalities, and more. But what does this look like in real life?

At a Glance | Tracking Climate Finance in Africa: Political and Technical Insights on Building Sustainable Digital Public Goods

In order to combat the effects of climate change, financing is needed to fund effective climate fighting strategies. Our white paper, “Tracking Climate Finance in Africa: Political and Technical Insights on Building Sustainable Digital Public Goods,” explores the importance of climate finance tracking, common barriers to establishing climate finance tracking systems, and five insights on developing climate finance tracking systems.

Data Strategies Playbook

Today, DG is pleased to announce the publication of our latest white paper, Designing Data Strategies: A Playbook for Action.

In this paper, we have identified six components for the design and operationalization of institutional data strategies: This work aims to distill lessons learned from Development Gateway’s research and collaboration, designing data strategies with development and humanitarian agencies. In the current ‘data revolution’ era, data and digital are both a strategic asset and a source of institutional risk.

Strategies should be designed using:

- a holistic approach,

- intentional leadership positioning, and

- a focus on the “right” investments.

Strategies should be operationalized through:

- responsible data practice,

- shared data use practices, and

- an appropriate governance plan.

We are continuously learning from our partners across various agencies, and hope this will be a useful starting point that may be adapted by organizational leaders to drive effective digital and data strategies in their institutional contexts.

Feedback about the approach outlined in this paper is welcome! Continue the conversation on social media using #DataStrategyPlaybook or by tagging @dgateway.

Share

Related Posts

Data on Youth and Tobacco in Africa Program Enters Phase II

The Data on Youth and Tobacco in Africa (DaYTA) program is launching its second phase, expanding to five additional countries. This blog highlights DaYTA’s objectives, innovative approach, and the key activities driving impact in adolescent tobacco control measures.

Launching a Partnership Matching Service for Nonprofits

While a lot of us have talked about the potential, value, and – in some cases – need for more mergers and acquisitions in the non-profit space, recent events have made it clear: now is the time. That’s why the teams at Accountability Lab, Development Gateway: An IREX Venture and Digital Public, partnered up to develop both a new toolkit, a partnership matching service, and professional support infrastructure aimed at assisting the organizations facing this challenge.

The Cancer-Tobacco Link: Using Data to Drive Stronger Tobacco Control Policies

As we observe World Cancer Day today, it is crucial to recognize the significant role smoking plays in the global cancer epidemic. Tobacco use is the leading preventable cause of cancer and cancer-related deaths worldwide, necessitating a dynamic, multidisciplinary approach to tobacco control interventions. DG’s Tobacco Control Data Initiative (TCDI) contains country-specific websites designed to

As we observe World Cancer Day today, it is crucial to recognize the significant role smoking plays in the global cancer pandemic. Tobacco use is the leading preventable cause of cancer and cancer-related deaths worldwide, necessitating a dynamic, multidisciplinary approach to tobacco control interventions. DG’s Tobacco Control Data Initiative (TCDI) contains country-specific websites designed to break down barriers to data use in tobacco control by consolidating reliable, comprehensive information on tobacco use, including its impact on cancer.

These 6 country-specific websites provide critical data that reinforces the well-established causal link between tobacco use and cancer, offering a clear, evidence-based picture of the public health threat. The websites feature a wide array of data sources, including primary data collected through TCDI, publicly available secondary data, and peer-reviewed research. By consolidating these resources, TCDI aims to fill existing data gaps and empower stakeholders with the information needed to strengthen tobacco control efforts.

Smoking is the predominant cause of lung cancer cases, responsible for around 85% of all cases worldwide. This is notable given that lung cancer is the principal cause of cancer-related deaths and ranks as the sixth leading cause of death worldwide. Tobacco smoke contains over 7,000 toxic substances, including seven carcinogens that cause cells to grow abnormally, eventually leading to cancer. Even smokeless tobacco, which is chewed, sucked, or sniffed rather than smoked, contains more than 4,000 chemicals—28 of which are known carcinogens. These alarming facts underscore the urgent need for continued awareness and action to reduce tobacco use in the fight against cancer.

Contrary to common beliefs, smokeless tobacco poses significant health risks, often underestimated in comparison to smoking. A single dose of snuff, held in the mouth for about 30 minutes, delivers as much nicotine as four cigarettes, leading to nicotine levels in the blood that can be as high—or even higher—than those from smoking. This makes smokeless tobacco highly addictive, with snuff being even more so than chewing tobacco. Users of smokeless tobacco are at increased risk of developing malignant tumors, particularly in the pancreas, esophagus, and mouth. These risks highlight the severe health consequences of smokeless tobacco, challenging the misconception that it is a safer alternative to smoking.

The Dangers of Secondhand Smoke

There is also a misconception that secondhand smoke is not as harmful as direct smoking. In reality, even brief exposure to passive smoke poses serious health risks to non-smokers. Therefore, there is no safe level of exposure to secondhand smoke, meaning that non-smokers who breathe in secondhand smoke can suffer from serious conditions like coronary heart disease, stroke, and lung cancer. Those living with smokers face a 20% to 30% increased risk of lung cancer due to secondhand smoke’s immediate adverse effects on the cardiovascular system. The dangers extend beyond lung cancer, with evidence linking secondhand smoke to an increased risk of breast cancer, nasal sinus cancer, stroke, atherosclerosis, and even adult-onset asthma.

Similar to active smoking, the longer the duration and the higher the level of exposure to secondhand smoke, the greater the risk of developing lung cancer. These risks underscore the urgent need to protect non-smokers from secondhand smoke in all environments.

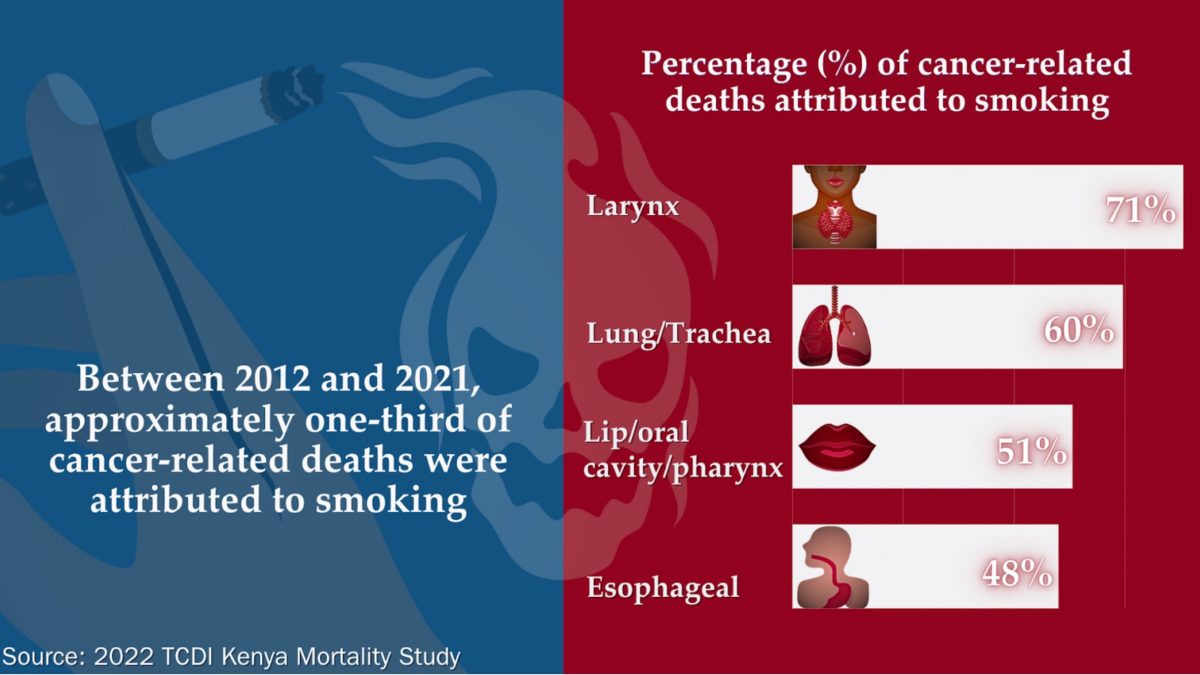

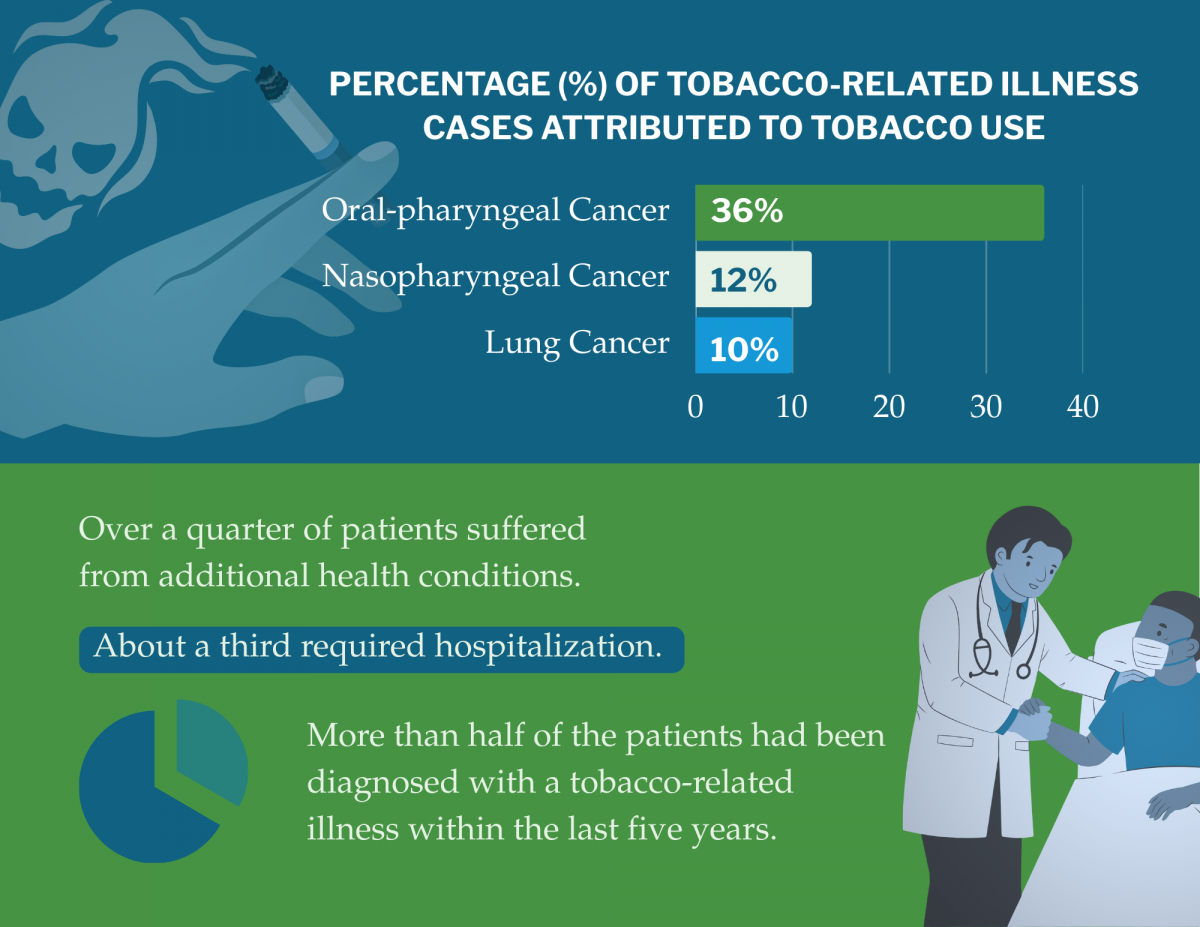

Cancer Deaths Attributed to TRIs in TCDI Focus Countries

Tobacco-related illnesses (TRIs) are a significant cause of cancer deaths worldwide, responsible for about 2.6 million cancer deaths in 2019 (the most recent year with available data), highlighting the urgent need for enhanced public health interventions. In Ethiopia, approximately 9,900 deaths are attributed to tobacco use annually, which contributes to a range of cancers as well as cardiovascular and respiratory diseases. Cancer, in general, accounts for 5.8% (2019) of the country’s total mortality, with 1,360 of those deaths directly linked to tobacco use. The cancers most commonly associated with tobacco include lung, laryngeal, esophageal, and oral cancers, among others, emphasizing the wide-reaching impact of tobacco on public health.

Similarly, in Kenya, tobacco-related cancers are responsible for a significant portion of the national cancer burden. A 2022 study, Tobacco Smoking-Attributable Mortality in Kenya, 2012–2021, provides the first comprehensive data on the morbidity and mortality linked to tobacco use in the country. This study found that nearly half (46%) of 2,000 Kenyan patients undergoing cancer treatment had a history of tobacco use, with oral-pharyngeal cancer emerging as the most common tobacco-related illness.

Men were disproportionately affected, making up 91.3% of the 9,934 deaths attributable to tobacco smoking, largely due to higher smoking rates among men.

These findings from both Ethiopia and Kenya underscore the devastating public health toll of tobacco use, particularly in the form of cancer-related deaths, and emphasize the critical need for multidisciplinary, evidence-based tobacco control strategies to reduce its impact.

Treatment and Healthcare Costs

TRIs not only devastate public health but also impose a heavy economic burden. According to Kenya’s 2022 study, the cost of treating patients with these illnesses is staggering, with lung cancer leading the way at $23,365 per case, followed by oral-pharyngeal cancer at $7,637. The majority of these costs stem from expenditures on medicine and medical staff. While cancers incur the highest treatment costs per case, they contribute less to overall healthcare spending compared to cardiovascular diseases. This is primarily because most cancer cases are diagnosed at advanced stages, limiting treatment options and resulting in poor outcomes and high fatality rates.

The Centre for the Study of the Economies of Africa’s (CSEA) study, Health Burden and Economic Costs of Tobacco Smoking in Nigeria, found that in 2019, 29,474 deaths were attributable to smoking, and the Nigerian healthcare system spends 526.4 billion Naira (the equivalent of USD 1.71 billion in 2019 NGN) in treating TRIs, annually. Researchers found that if the price of cigarettes were to increase by 50%, 23,838 deaths would be forestalled and the government would benefit from healthcare cost savings and increased tax revenue collection.

In 2021, TRIs in Kenya were responsible for significant economic losses, yet the revenue generated from the tobacco industry—through taxes and other contributions—covered only 63.8% of the estimated healthcare expenditures caused by tobacco use. This stark gap between the costs of treating TRIs and the revenues from tobacco taxation underscores the unsustainable economic impact of tobacco consumption.

Policy Recommendations for Public Health Interventions

Reducing cancer deaths linked to tobacco-related illnesses requires a dynamic, multidisciplinary approach to tobacco control that adapts to the political, socioeconomic, and cultural context of each region. Several strategies are essential across all six TCDI focus countries—Zambia, South Africa, Kenya, Ethiopia, DRC, and Nigeria. First, reinforcing the implementation of the Framework Convention on Tobacco Control (FCTC) to reduce tobacco use prevalence.

Alongside this, robust cessation programs must be integrated into diverse settings, including health facilities, workplaces, higher education institutions, and communities, to reach individuals across various stages of life and socio-economic backgrounds. Given that tobacco use is responsible for far more cancers than other adjustable behaviors– like consuming alcohol or physical inactivity–interventions aiming to help individuals quit smoking could have the most significant global impact on cancer prevention.

Gender mainstreaming is also vital; tobacco control policies and interventions should be designed with a gender perspective, recognizing the differing prevalence of tobacco use and associated health outcomes between men and women.

Further, comprehensive data collection is necessary to assess and monitor the tobacco epidemic effectively. This includes systematically gathering data on both morbidity and mortality rates related to tobacco use, such as the incidence of lung cancer, cardiovascular diseases, and respiratory disorders. In addition to clinical data, there should be linkages between electronic health records and national registries to enable real-time monitoring and trend analysis. Surveys and population-based studies can also provide insights into tobacco use patterns, including initiation, cessation rates, and the social determinants influencing tobacco consumption. This robust data collection will allow for consistent, evidence-based policy adjustments and interventions, ensuring that strategies to reduce tobacco use are responsive to local context and effective.

Expanding the scope of research to include tobacco-related morbidity, mortality, and the economic impact of diseases not covered in existing studies will offer a more complete picture of the toll of tobacco. Equally important is the responsible management of tobacco funds—resources collected from the tobacco industry should be used prudently to finance cessation programs and support healthcare costs associated with treating tobacco-related illnesses.

Finally, progressively increasing tobacco taxes remains one of the most effective tools to reduce consumption and alleviate the financial burden on healthcare systems. By combining these efforts into a cohesive, integrated approach, countries can make significant strides in reducing the devastating impact of tobacco use on public health.

Building Procurement Back, Better

This is the third blog in a three-part series exploring how governments can build resilient procurement systems. Development Gateway has been working on a project for the UK Government Digital Service (GDS) Global Digital Marketplace Programme and the Prosperity Fund Global Anti-Corruption Programme, led by the Foreign & Commonwealth Office (FCO), which included the topic of Covid-19 procurement response.

Read the full Emergency Procurement: Lessons Learned from Covid-19 report, and read blogs one and two in this series.

The IMF predicts the global economy will shrink by 4.9% this year as a result of the Covid-19 pandemic. According to a Gartner market analysis, the global IT market will shrink by 8% in the next year as a result of the recession.

However, the government technology market is expected to be more resilient, shrinking by only 0.6%. In fact, two government technology sectors – IT services and software – are predicted to grow in 2020 despite the severe global economic downturn.

How is government digital transformation growing, rather than shrinking?

As governments look to “build back better,” we can expect an influx of government spending to stimulate the economy, and a shift in priority goods and services to purchase. As the world transitions from emergency response to recovery, governments’ focus will shift from using technology to procure other products (as we described in our first blog in this series), to procuring technology products themselves. For example, Covid-19 has underscored the need for digital governance: not only digitizing government processes and workforces, but also the services provided to citizens — including education, health, registration authorities, housing and citizenship applications, etc.

Covid-19 has accelerated government digitization efforts across the globe as Ministries of Education shift to online learning, Ministries of Health roll out telemedicine services, and government employees continue to telework and access secure government servers via the cloud. Digital transformation is no longer a choice, but a core need. Working on extremely short timelines, to meet an entirely new set of needs, governments have relied heavily on existing and new digital solutions to meet increasing demands. However, longer-term investments in government digital service delivery require more rigorous procurement and design considerations.

Digitalization to support and rehabilitate local economies

Increased government spending on digital and IT services will not only streamline public service delivery, but also stimulate the economy. Redirecting government spending to domestic IT suppliers and local SMEs provides the added benefit of supporting local economies as they begin to rebuild from the initial shock of Covid-19. This presents a ripe opportunity to create jobs and stimulate the economy – but understanding who well-qualified domestic IT suppliers are, and the barriers they face to engaging with public procurement processes, is critical for making sustainable and effective investments. For example, the Indonesian Ministry of Health and National Standardisation Agency are relaxing noise restrictions on ventilators so that domestic manufacturers can speed up production. Adaptive and flexible procurement policy reforms such as these can help ensure efficient government spending during, and after, an emergency. Created in partnership with the Global Digital Marketplace Programme, DG’s indicator framework is a tool that can help governments understand and take smaller steps from their current “as-is” state to get to their desired “to-be” state of digital procurement reform.

The path – and the tools – to rebuilding responsibly

Moving forward, global government buyers that seek to procure digital solutions must take lessons from Covid-19 into account regarding user needs and holistic approaches.

Fortunately, the body of resources for governments looking to build resilient digital solutions is growing. For example, buyers can refer to OECD research and digital strategies to consider how policy compliments digitization; draw on knowledge from Australia and the United Kingdom which have both put together criteria/codebooks on digital service delivery; and prioritize user-centered design principles to ensure that digital solutions are used, useful, and build resilience.

The Emergency Procurement Report: Lessons Learned from Covid-19 report and indicator framework are key resources for country governments looking to responsibly adapt procurement operations to address Covid-19. We encourage wide use of the tool to identify where to strengthen procurement responses during emergencies, sustain government services, and support the economy during and post-crisis.

Related Posts

Resilience by eDesign: Digital Emergency Procurement

In a global emergency, public spending helps acquire materials to respond to the crisis, and stimulates the economy to assist with post-crisis recovery. In recent months, DG set out to understand what public procurement policies, contracting mechanisms, and data and digital capabilities were required to procure a rapid and effective emergency response.

Procurement Data and COVID-19: Buying Smarter in a Crisis

Achieving resilient public procurement goes beyond digitization and automation: data generated through these processes must also be used by government to make smarter decisions – particularly during crisis – and by civil society to hold government accountable for those decisions.

When Covid-19 Confirms the Need for Open Contracting in Senegal

Each year, governments spend trillions of dollars through public procurement of goods and services – without a focus on accountability, much can be lost through waste or corruption. Today, more than ever, transparency in public procurement and Open Contracting is needed in Senegal and around the world as governments respond to and recover from the Covid-19 pandemic.

In Kenya, Open Contracting Improves Efficiency & Curbs Corruption

On 31st August 2020, President Uhuru Kenyatta directed the Ministry of Health to come up with a transparent, open method and mechanism through which all tenders and procurement done by Kenya Medical Supplies Agency (KEMSA) will be available online. The directive follows allegations of corruption in the procurement of COVID-19 emergency supplies.

With citizens’ lives on the line and government spending at record highs, ensuring accountability to citizens is imperative to maintaining trust and effectively managing KEMSA’s procurement in response to COVID-19. Open procurement data can help in improving the efficiency of emergency procurement and support civil society groups to detect corruption and monitor the effectiveness of service delivery.

“This level of transparency and through the use of technology will go a very long way in ensuring that we have the confidence of our people that those placed in institutions are able to manage the resources of the Kenyan taxpayer plus our development partners in an open and transparent manner” – President Uhuru Kenyatta

Much can be learned from Makueni County in Kenya, a county that publishes and uses open, accessible, and timely information on government contracting to engage citizens and businesses. The Makueni Open Contracting Portal is an interactive site built by Development Gateway (DG) that provides detailed information on each step of the tender, award, and contract implementation process at the county level. These steps are now recorded within the interactive Makueni Open Contracting Portal – making information available for citizens at each step of the process. The county plans to go a step further to publish all implementation data such as community monitoring reports, also known as PMC reports and supplier payment vouchers.

The goal of the portal is to improve the efficiency of public procurement management and support the delivery of higher-quality goods, works, and services for residents of Makueni County through enhanced citizen feedback.

What We Learned from Makueni County

Lesson 1: Public Data Improves Efficiency

The primary role of the Ministry of Health and KEMSA in Kenya during an emergency situation is to provide citizens timely, affordable, and efficient supplies and services. Digitizing and publishing procurement data will provide the Ministry insights on whether funding and services are reaching intended beneficiaries.

Publishing procurement data will also encourage better monitoring from relevant state and non-state actors. The Ministry of Health and KEMSA will have the opportunity to aggregate non-state actors’ feedback and state actor insights. This feedback will enable them to make data-driven decisions that will improve service delivery to citizens, promote efficient allocation of resources and ultimately saving costs.

DG has developed interactive M&E dashboards to support analysis currently used by Makueni County. The series of charts and visualizations provide helpful data insights – such as top suppliers that received contracts and the percentage of awards that go toward the Access to Government Procurement Opportunities (AGPO), which requires tenders to be awarded to women, youth, and people with disabilities.

Since the start of the use of the Makueni open contracting portal in 2019, improved resource utilization and efficiency in procurement has been identified by the County leadership. Governor Kivutha Kibwana cited that the County has saved Kes. 30,000,000 from the Roads department as a result of using the portal.

Lesson 2: Building Trust is Essential to Combating Corruption

The complexity of emergency responses such as COVID-19 requires cooperation between the private sector, national, and county government to ensure timely delivery of supplies. KEMSA publishing data will promote feedback and engagement of business and citizens further building trust and collaboration. Publishing procurement data also equips civil society and citizens with the information needed to help combat corruption. For example, reporting counterfeits, frauds, and scams – which has been a key corruption issue identified globally in COVID-19 response procurement, particularly PPEs.

DG has implemented its corruption risk dashboard in Makueni, which uses high powered analytics and global research to identify risk profiles for potential corruption in procurement. KEMSA can adopt the corruption risk dashboard as a red-flagging tool to assist in identifying procurement activities that merit in-depth auditing of corruption risk – including fraud, collusion, and process rigging – over time. These analytics will allow the organization to address cases of corruption before taxpayer money is lost.

Lastly, publishing Beneficial ownership data can enable governments to quickly perform minimal standards of due diligence on companies they are buying goods and services from. As well as reducing the immediate risk of corruption, beneficial ownership data provides a valuable trail for future audit.

Related Posts

Introducing The HackCorruption Civic Tech Tools Repository

Introducing the Civic Tech Tools Repository: an open-source hub of digital solutions to fight corruption. Designed for growth through GitHub contributions, it brings together tools, code, and resources across six key areas for HackCorruption teams and beyond.

From Standardization to Specificity: Localizing Multi-Country Research

Multi-country research must balance consistency with local realities. While standardization allows reliable comparisons and generalizable insights, local context shapes outcomes. This blog explores how programs can strike that balance effectively.

Economic Toll of Tobacco-Related Diseases in Kenya: New Research Findings

Development Gateway: An IREX Venture (DG) is pleased to announce the publication of a research manuscript on the Economic Costs of Tobacco-Related Illnesses in Kenya. This research was carried out as part of the Tobacco Control Data Initiative (TCDI) activities in Kenya and is part of a broader report on Morbidity and Mortality from Tobacco Use in Kenya.

Development Gateway: An IREX Venture (DG) is pleased to announce the publication of a research manuscript on the Economic Costs of Tobacco-Related Illnesses in Kenya. This research was carried out as part of the Tobacco Control Data Initiative (TCDI) activities in Kenya and is part of a broader report on Morbidity and Mortality from Tobacco Use in Kenya. Data from this research is available on the TCDI Kenya dashboard, which aims to supply decision-makers in government, members of civil society, and academia with improved access to country-specific data to better inform tobacco control policy.

Published in August 2024 in the Tobacco Use Insights journal, this is the third of three manuscripts that seek to break down the research report’s findings. The first, published in November 2023, explored the prevalence, patterns, and factors associated with tobacco use among patients with tobacco-related illnesses (TRIs), such as cancers, cardiovascular disease, chronic respiratory disease, and diabetes. The second, published in July 2024, focused on Mortality from Tobacco Use in Kenya. You can access its accompanying blog post here.

This blog highlights some key findings in the manuscript, based on the research carried out in Kenya from 2021-2022, estimating the direct, indirect, and ultimately economic costs of tobacco use for the period studied.

Why research on the economic burden of tobacco use in Kenya?

Indirect and direct medical costs of treating TRIs can place a significant economic burden on societies through healthcare and productivity losses. This is especially true for low- and middle-income countries (LMICs), which bear the brunt of the global tobacco crisis, accounting for a staggering 80% of tobacco-related deaths worldwide. As a result, assessing the economic impact of tobacco consumption in LMICs is crucial for shaping effective tobacco regulation and policy. However, this has been understudied in Africa, and the data that is available remains scant. In Kenya, estimating the economic costs of tobacco use is imperative to making informed, evidence-based policy decisions.

This manuscript not only reveals the direct financial burden of tobacco use but also offers a solid foundation for defining the necessary policy actions to address its harmful health and economic consequences. Additionally, it highlights the far-reaching effects of exposure to secondhand smoke for non-smokers, responsible for an estimated 1.3 million deaths annually worldwide. Barring effective tobacco control interventions, LMICs will be up against higher tobacco-related healthcare costs, placing even more strain on already overwhelmed healthcare systems.

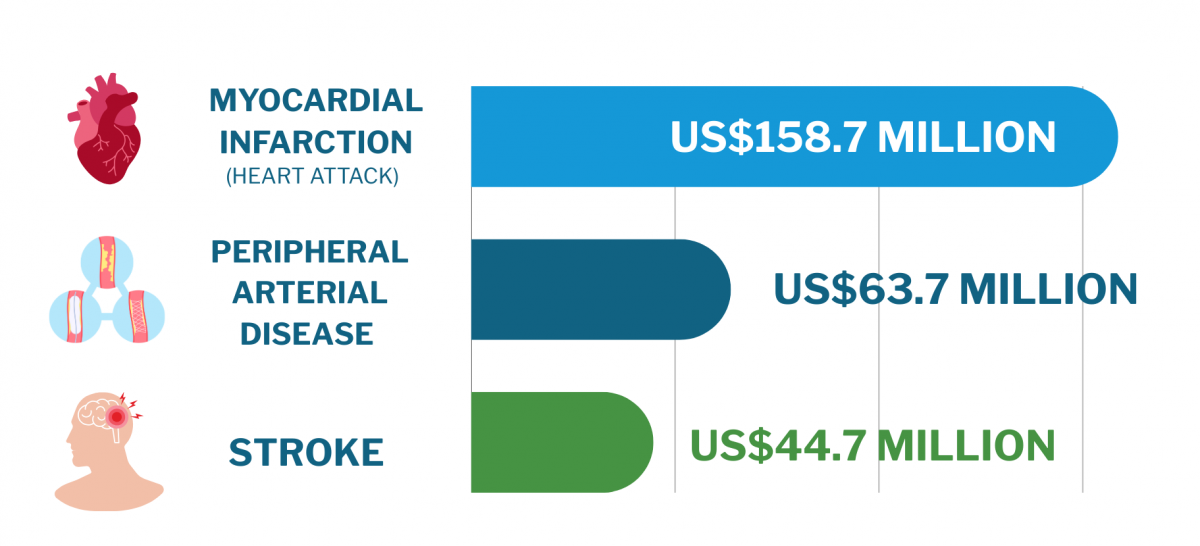

Key Findings from the Research

The estimated healthcare costs linked to tobacco use in Kenya are an alarming US$396.1 million (approximately 53.4 billion KES). Among the tobacco-related illnesses (TRIs) studied, myocardial infarction (heart attack) was the leading cost driver, accounting for US$158.7 million (approximately 21.42 billion KES). Following that, peripheral arterial disease and stroke each contributed US$63.7 million (approximately 8.74 billion KES) and US$44.7 million (approximately 6.02 billion KES) in healthcare expenses, respectively. A significant portion of these costs -over 90% – is driven by the expense of medications required to manage these conditions.

Regarding productivity losses due to tobacco-related illnesses, the costs range from US$148 (approximately 19,980 KES) per person to US$360 per person (approximately 48,600 KES), making up between 27% and 48% of the total economic burden. Productivity losses from the diseases ranged between US$148 (approximately KES 19,980) and US$360 (approximately KES 48,600), accounting for 27% to 48% of the economic costs.

In terms of healthcare costs per case, lung cancer was the most expensive, costing US$23,365 (approximately KES 3,150,275) per case, followed by oral-pharyngeal cancer at US$7,637 (approximately KES 1,031,995), and laryngeal cancer at US$6,922 (approximately KES 933,470).

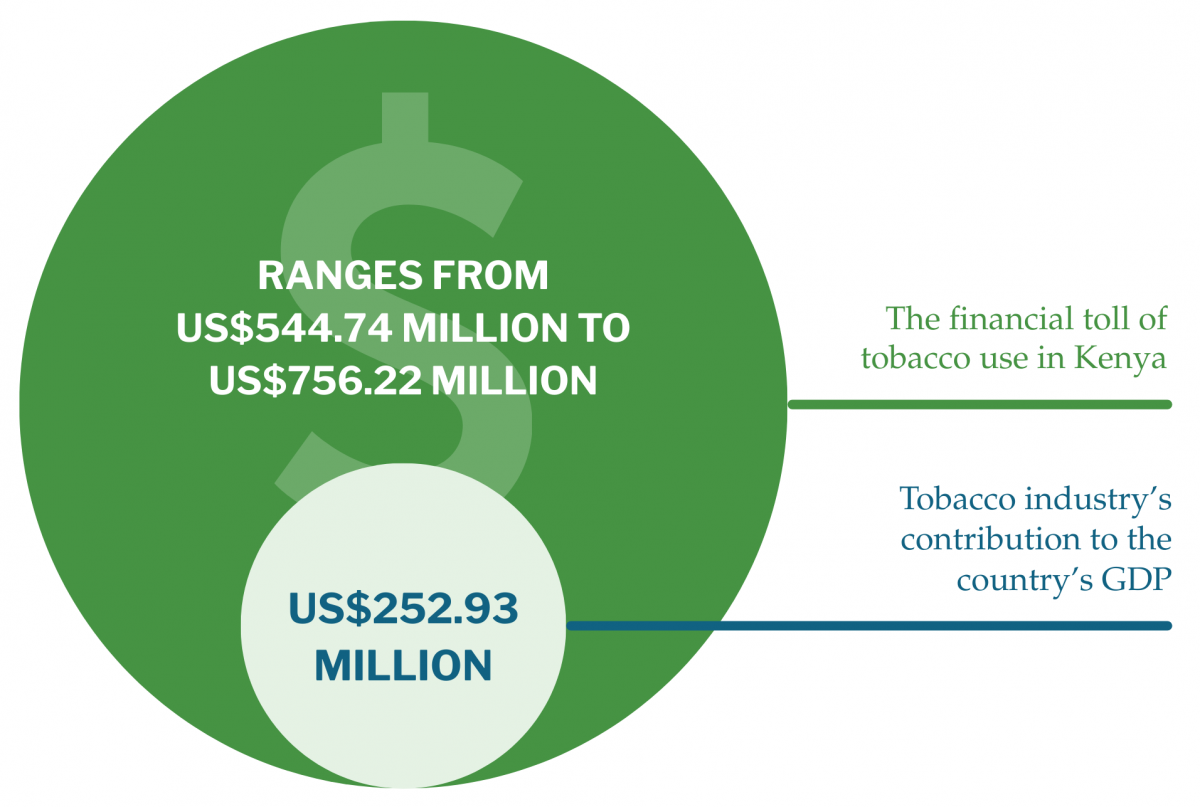

In 2022, the tobacco industry in Kenya generated $7.35 million in revenue, representing 7% of the country’s GDP of US$105 billion. However, the economic cost of tobacco use – just for the illnesses included in the study – accounts for more than 34% of this revenue. In other words, the financial toll of tobacco use in Kenya ranges from US$544.74 million (approximately KES 73.5 billion) to US$756.22 million (approximately KES 102.1 billion), while the tobacco industry’s contribution to the country’s GDP is much smaller at US$252.93 million (approximately KES 34.1 billion).

When comparing these figures, tobacco use results in a net loss to the economy of between US$291.8 million (approximately KES 39.4 billion) and US$503.3 million (approximately KES 67.9 billion) each year. This means that for every dollar the tobacco industry earns, the economy loses between KES 297 and KES 405 in healthcare costs and lost productivity, illustrating a poor return on investment.

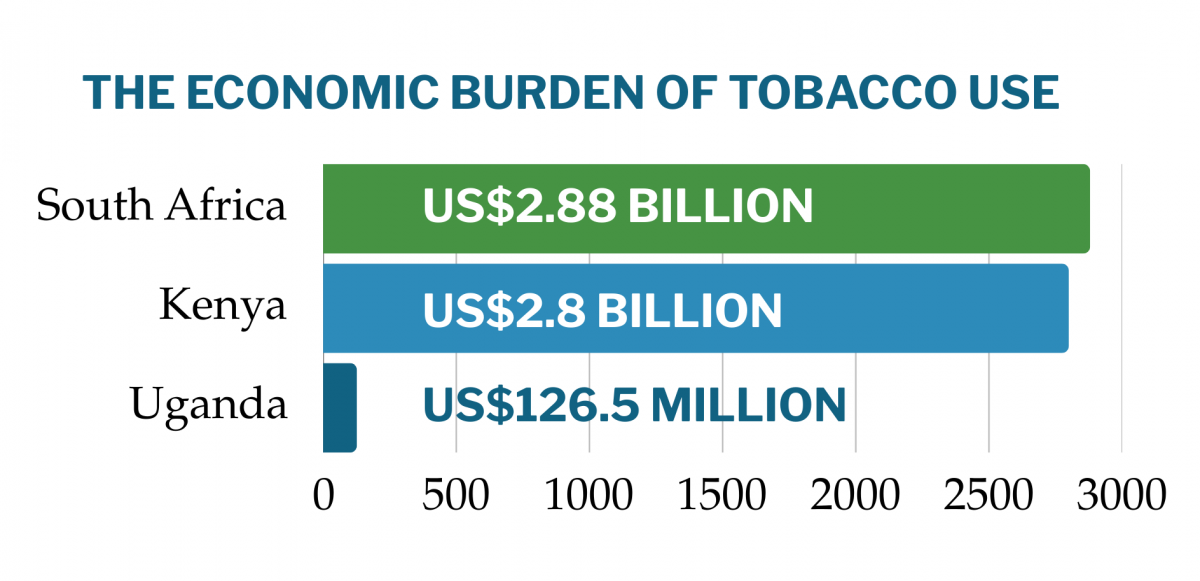

The analysis further shows that treating tobacco-related illnesses (TRIs) in Kenya is an enormous financial burden on the healthcare system, with total treatment costs estimated at US$2.8 billion (approximately KES 378 billion). Of this, US$396.1 million (approximately KES 53.4 billion) is attributed explicitly to tobacco use, accounting for 14% of the overall costs of managing these diseases. In terms of comparison, the economic burden of tobacco use in Kenya is somewhat less than in South Africa, where the cost is US$2.88 billion (approximately KES 388.8 billion), but more than in Uganda, where the cost is US$126.5 million (approximately KES 17.1 billion).

These differences can be attributed to varying smoking rates and the prevalence of tobacco-related illnesses in each country.

Implications for Policy

To address the economic and health impacts of tobacco use in Kenya, several key policy recommendations can be made:

- Strengthen Tobacco Control Laws: Implement comprehensive tobacco control legislation, enforce existing laws rigorously, and increase taxes on tobacco products to make them less affordable and accessible.

- Promote Cessation Programs: Advocate for the introduction of more support services for people trying to quit smoking, as well as monitor the tobacco industry’s activities to ensure they comply with existing regulations.

- Engage Stakeholders and Raise Awareness: Build stronger collaborations with relevant stakeholders, run public awareness campaigns to educate people about the dangers of tobacco use, and encourage policymakers to prioritize tobacco control on the national agenda.

- Capacity Building for Enforcement: Invest in strengthening enforcement mechanisms and provide training for healthcare professionals on effective tobacco cessation strategies.

- Leverage International Partnerships: Work with international organizations to tap into their expertise and resources, ensuring the successful implementation of tobacco control measures.

- Adopt Global Best Practices: Align local policies with global best practices and evidence-based strategies to enhance tobacco control efforts in Kenya.

- Use Research to Inform Policy: Use ongoing research and data to develop evidence-based policies supporting tobacco cessation and reducing tobacco-related harm.

By adopting these policy measures, Kenya can mitigate the significant economic burden of tobacco use and work towards better health outcomes for its population.

If you would like to learn more about TCDI and explore country-specific data, kindly visit www.tobaccocontroldata.org.

Procurement Data and COVID-19: Buying Smarter in a Crisis

This post is the second in a 3-part blog series focused on DG’s collaboration with the Global Digital Marketplace Programme. Read part one “Resilience by eDesign: Digital Emergency Procurement” here, and stay tuned for Blog 3 in which we’ll discuss building procurement back, better, after Covid-19.

Achieving resilient public procurement goes beyond digitization and automation: data generated through these processes must also be used by government to make smarter decisions – particularly during crisis – and by civil society to hold government accountable for those decisions. With citizens’ lives on the line and government spending at record highs, ensuring accountability to citizens is imperative to maintaining trust and effectively managing emergency response. Open procurement data can help civil society groups detect corruption and monitor the effectiveness of service delivery.

For example, In a bid to expedite PPE procurements and ensure timely availability of critical supplies, many countries moved to direct purchasing avenues that differ from traditional procurement. In some cases, “speed” has led to identified cases of corruption. In South Africa, this led to the government reverting back to its old procurement processes, and taking further steps to curb corruption and rebuild trust. These steps included publishing the identities of all winners of PPE contracts, rationale for selection, and names of losing bidders; the government also plans to publish the shareholder names of winning bidders.

The nature of Covid-19 requires rapid and informed resource allocation. Procurement data can help governments achieve this goal through understanding what priorities are; setting expectations for how much should be spent to achieve priorities; and ensuring suppliers are credible and can deliver.

First: knowing what and who to prioritize enables governments to focus scarce resources on purchasing the most critical items, and delivering them to communities most at risk.

Data from healthcare providers, sub-national and national procurement entities should be aggregated to understand needs and further inform budgeting. Publishing budget information and engaging with civil society can help authorities conduct spot-checks and ensure that funding and services are reaching intended beneficiaries.

Second: to curb price gouging, governments should publish up-to-date price lists for reference and use by all public procuring entities.

For example, as demand for personal protective equipment (PPE) soared in the early days of the crisis, so did PPE prices. Intermediary purchasers also flooded the market, looking to skim off profits by connecting desperate buyers with suppliers. Publishing information on prices, quantities of PPE distributed and engaging with civil society encourage citizens and procurement officers alike to monitor corruption risks.

Third: leveraging market intelligence – using data from existing procurement systems (such as IFMIS) and investing in new data sources – can speed up due diligence processes.

In many countries, procurement systems collect supplier data and efforts can be made to enhance this data to include financial solvency, sector qualifications, beneficial ownership information, and supplier performance evaluation(s). On its own, beneficial ownership data can enable governments to quickly perform minimal standards of due diligence on companies they are buying goods and services from. As well as reducing the immediate risk of corruption, beneficial ownership data provides a valuable trail for future audit.

Fourth: as mentioned throughout, publishing procurement data equips civil society and citizens with the information needed to help combat corruption.

For example, identifying and reporting fraudulent applications for relief funding; monitoring the use (or misuse) of emergency response funds; and reporting counterfeits, frauds, and scams. To enhance citizen oversight, the Government of Paraguay launched a mobile app that notifies users about everything the state procures during the Covid-19 emergency, from tender through award. In Makueni County, Kenya, Development Gateway is supporting the county government in enhancing the Makueni Open Contracting Portal (that publishes data in OCDS) to include Covid-19 procurement data. The County plans to tag all Covid-19 tender data in the system track and analyze this data to inform government decisions, and involve civil society and communities in the improvement of emergency procurement processes.

➙ track supplies needed against supplies procured; ➙ track supplies needed against supplies procured;➙ pool purchase orders across government administrations; ➙ identify and select suppliers quickly; ➙ extract contract data for market intelligence; ➙ open data for public oversight and transparency; ➙ protect existing suppliers and long-term economic sustainability. |

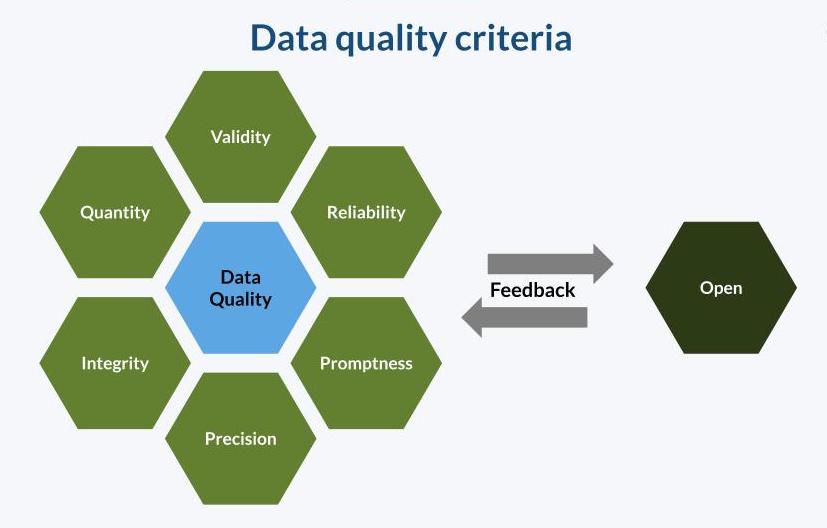

Finally: while resources to build complex procurement data management systems may be difficult to mobilize, alternative data collection mechanisms can achieve much the same effect.

For example, standardized Excel templates or web forms that can be used to aggregate data from all relevant procurement entities. If open budget portals or websites do not exist, other tools and resources such as the Open Fiscal Data Package standardize the structure and the content of budget data so as to ensure data quality.

Another valuable resource for understanding how to collect and publish Covid-19 data is the Open Contracting Partnership’s guide to Covid-19 procurement data collection, publication, and visualization.

Related Posts

Building Procurement Back, Better

As governments look to “build back better,” we can expect an influx of government spending to stimulate the economy, and a shift in priority goods and services to purchase. While the world transitions from emergency response to recovery, governments’ focus will shift from using technology to procure other products, to procuring technology products themselves.

Resilience by eDesign: Digital Emergency Procurement

In a global emergency, public spending helps acquire materials to respond to the crisis, and stimulates the economy to assist with post-crisis recovery. In recent months, DG set out to understand what public procurement policies, contracting mechanisms, and data and digital capabilities were required to procure a rapid and effective emergency response.

When Covid-19 Confirms the Need for Open Contracting in Senegal

Each year, governments spend trillions of dollars through public procurement of goods and services – without a focus on accountability, much can be lost through waste or corruption. Today, more than ever, transparency in public procurement and Open Contracting is needed in Senegal and around the world as governments respond to and recover from the Covid-19 pandemic.