Preparing Jordan’s Education System for the AI Age

Global education is at a crossroads: 250 million children and youth are out of school, and around 70 percent of 10-year-olds are unable to read and understand a simple text, a sharp increase since before the pandemic. Early grade education (EGE) is critical to reverse these trends, as it sets the foundation for children’s lifelong learning, cognitive development, and future opportunities, making it a cornerstone of national prosperity. The early years (birth through age 8) are marked by rapid brain development in young children, underscoring the urgency of investing in quality early learning. Research in various contexts, including studies referenced by UNESCO, suggests that EGE provides a 13% return through improved health and social cohesion.

Jordan has taken important steps in recent years to strengthen early grade education – which is referenced as a priority within its national economic modernization vision – including curriculum reform, teacher training, and the rollout of e-learning platforms. Education Reform for the Knowledge Economy programs (ERfKE I and II) and other ongoing education sector reforms have contributed to the country’s high primary school (grades 1-6) enrollment rate of 98-99%, positioning it in the upper-middle range of the MENA distribution for primary enrollment. Within this context, the Early Grade Education Activity, Asas (“foundation” in Arabic), is an IREX-led program, funded by the U.S. Embassy in Amman, and supported by Development Gateway: An IREX Venture (DG) and other consortium partners that is strengthening pre- and in-service teacher education while improving Kindergarten to Grade 3 foundational literacy, numeracy, and socio-emotional skills across Jordan.

Within ASAS, DG is supporting the development of a comprehensive data-informed environment that gives universities, teachers, schools, and the government the data and data governance policies needed to improve student learning across the entire country. For example,

- DG supports Jordanian university partners by developing data systems and dashboards that strengthen accreditation, institutional improvement, and support for student teachers.

- DG also works with IREX to integrate data on teachers’ professional development, career progression, classroom observation scores, and school performance into interoperable systems that can generate teacher and student “report cards.” These tools give decision-makers a clearer picture of where teaching is most and least effective and guide targeted and differentiated interventions.

- At the national level, DG supports IREX’s policy work by advising on data governance policies, with a focus on managing sensitive early grade data responsibly and securely.

Cutting across this data-informed environment is ongoing work to explore how ‘AI-ready’ the Jordanian early grades education system is, balancing AI’s powerful new ways to aggregate and analyze education data while addressing concerns about negative impacts on critical thinking, creativity, and equity.

What Meaningful AI Readiness Looks Like

There is a global race underway to develop AI tools. While education technology firms are developing AI-enabled features, students themselves are already bringing AI into the classroom. According to a 2025 report from HP, 61% of students are already using generative AI. The impact of AI on student learning and career preparation demands a shift toward a secure, responsible, and effective AI implementation that centers on core educational outcomes rather than a tools-first approach.

Cameron Mirza, Director for Asas at IREX, speaking at Times Higher Education’s Arab Universities Summit in Jordan, cautioned that universities’ “fear of missing out” on AI may be driving rushed decisions that overlook the financial sustainability of their AI models, leading to money being spent poorly. Universities must also confront whether they have the infrastructure needed to ensure equitable access. As Nader Sweidan, a digital transformation expert at Al-Ahliyya Amman University in Jordan, notes, “only about 45 percent of students [here] have consistent access to the kind of internet service that AI applications require.” Realizing the desired impact of AI for Education is about more than just selecting the right tools and skills, it is further shaped by the use of strong data systems, alignment with policies and objectives for digital sovereignty, and the recognition and reinforcement of trust building between teachers and students.

Impactful AI systems require strong data systems that are representative, reliable, and well-governed. DG’s Guide for Education Technology Systems underscores the importance of robust Education Management Information Systems (EMIS) and Learning Management Systems (LMS) as complementary pillars of a modern education ecosystem. EMIS platforms support ministries with planning, monitoring, and resource allocation, while LMS platforms enable design, delivery, and assessment of teaching and learning – including through AI-enabled features – and when integrated, they can connect student-level performance data with system-level policy decisions. This perspective has shaped our approach to the implementation of the AI Accelerator in Asas, where we are emphasizing high-quality, sustainable data pipelines as a prerequisite for responsible AI adoption rather than an afterthought.

Digital sovereignty is another critical construct for AI readiness efforts to consider. DG has a long track record of prioritizing open-source solutions as a technology preference wherever feasible. As we have recently written about in our Digital sovereignty and open source: the unlikely duo shaping DPI blog, open-source technologies can help countries assert sovereignty over their digital infrastructures by avoiding proprietary lock-in and increasing transparency over system architecture.

Finally, one lens too often neglected in the current rush to adopt AI tools for education is the need for preserving and strengthening trusted student-teacher connections. While digital and physical infrastructure are critical, relationship building is equally essential: strong, trusting student‑teacher relationships create the psychological safety students need to participate, take risks, and truly learn. In an AI‑enabled world, this human connection is the teacher’s irreplaceable value, turning content into real learning and schools into genuine communities.

Introducing the AI for Education Accelerator Program

Working in partnership with the Jordanian Ministry of Education (MoE), IREX, and DG are conducting a national AI readiness diagnostic assessment. The assessment will inform education policy and decision-makers on how prepared the Jordanian early grades system is to integrate AI safely, sustainably, equitably, and effectively.

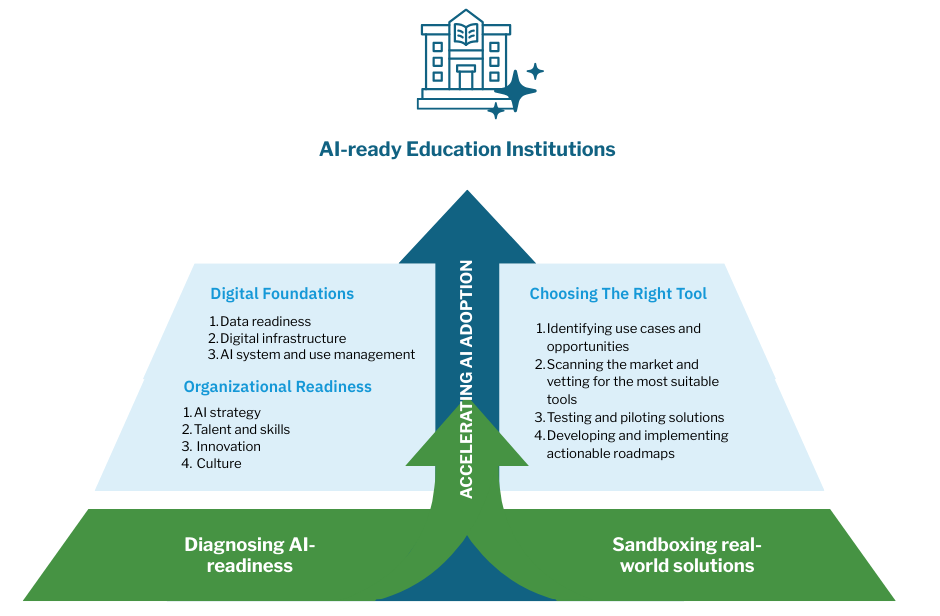

The assessment is based on IREX and DG’s new AI for Education Accelerator program. The Accelerator is built on two interlinked foundations:

- First, an AI readiness diagnostic assessment – implementable at both the ministry and university or school level – assesses organizational readiness (strategy, skills, innovation culture) and digital foundations (data readiness and governance, infrastructure, AI management and stewardship). This assessment integrates two complementary data collection tools: 1) a Teacher and Parent Survey of 5,000 early grades teachers and 400 parents of early grades students, and 2) in-depth Key Informant Interviews (KIIs) with ministry officials, field directorates, school leaders, and other stakeholders. Together, these tools provide both quantitative and qualitative insights on current AI use, perceived opportunities and risks, needed training and safeguards, and system-level readiness. They offer a comprehensive, system-wide view of AI readiness in Jordan’s education sector and provide an evidence base to develop an ambitious-but-achievable strategy for responsible, effective, and sustainable AI adoption.

- Second, a bespoke AI sandboxing process supports universities and schools to identify use cases, scan the global AI market, prototype shortlisted tools (or scope the development of new tools where gaps exist) that fit with the local context in safe staging environments using synthetic datasets, and develop actionable roadmaps to implementation.

The accelerator is being implemented in full partnership with the MoE. The process is being guided by a steering committee composed of representatives of a number of MoE departments, and MoE staff are actively involved in data collection, including through both engaging in interviews and supporting the piloting and roll-out of the survey. As the assessment progresses, MoE staff and education experts will be actively involved in the data analysis phase of the process, too.

This approach recognizes that sustainable implementation of AI in education systems is not about chasing the newest tool, but about ensuring leaders understand and trust AI’s potential while having the governance structures, skills, values, culture, and technical capacity to oversee and implement AI responsibly to generate cost-effective improvements to EGE delivery.

Accelerating Impact in Education in Jordan and Beyond

Looking ahead, we will continue working with Jordan’s Ministry of Education to complete the AI readiness diagnostic, with the intention that findings will guide strategic AI integration in early grade education for years to come. In parallel, we plan to implement the Accelerator program with our university partners, supporting them to identify and test AI use cases in teacher education, student support, institutional administration, faculty development, quality assurance and other priority areas.

Our work on AI in the Jordanian education system also feeds into our broader work on digital public infrastructure (DPI), where we are focusing on strengthening data exchange architectures and governance. Implementing AI readiness assessments and sandboxing in Jordan offers real-world evidence on how automation can be effectively, safely, and sustainably integrated into complex education data systems – evidence and experience that is directly relevant to inform our engagements in global DPI conversations.

Optimizing the impact — and insulating against the very real risks — of AI for education takes a rigorous, holistic, and adaptive approach to understanding educational institutions and the children and communities they serve. These tools and methods are being developed with adaptation in mind. and we are actively discussing collaboration with Universities in the region, and across West, East, and Southern Africa. By linking foundational early grade reforms, robust data systems, and a pragmatic, sovereignty-aware approach to AI, Jordan offers a practical blueprint for how education systems in lower- and middle-income countries can prepare for AI in ways that are safe, ethical, and aligned with national priorities.

Beyond the Algorithm: The Case for Human Judgment in AI

Currently, we are hearing that artificial intelligence (AI) will change everything that we do, from classrooms to how we get health care, how we harvest crops, and how we distribute fertilizer. Some are asking a simple question: how do we make these tools genuinely useful, ethical, and sustainable? As we try to keep pace with the advancements and figure out what is “smoke and mirrors” versus what is a genuine application, we believe that there’s no approach that removes the human in the loop (HITL). At least for now.

Human-in-the-loop generally refers to “the need for human interaction, intervention, and judgment to control or change the outcome of a process, and it is a practice that is being increasingly emphasized in machine learning, generative AI, and the like.” In practical terms, it means that human intelligence is deliberately included in the supervision, training, and decision-making rather than leaving it to an automated algorithm.

Why include humans?

There are many arguments for including humans in the loop; here are the most salient:

- Improvements in decision quality because humans can apply domain expertise, contextual understanding, and common sense to AI recommendations to catch what edge cases the AI misses (e.g., nuanced scenarios where human empathy is required to override standard protocol)

- Ethical oversight and accountability: decision-making systems do not have the capacity to exercise moral judgments; there has to be some form of safeguard against discriminatory or harmful automated decisions.

- Transparency: humans can explain decisions, adjust workflows, and take feedback, things that black boxes can’t do.

- Learning from experience remains a fundamentally human feature; machines learn patterns, while genuine human learning means internalizing lessons and changing behavior reliably over time. Machines may adjust to feedback, but people can truly embed and sustain change.

As the AI space grows rapidly, the need for human-in-the-loop interactions remains crucial, particularly as AI becomes more autonomous and the impact of its decisions bigger. Human oversight is needed to ensure that AI agents adhere to ethical boundaries, correct system failures, and maintain alignment with human objectives. The risk of a runaway or misaligned agent necessitates the stopgap that having a human in the loop provides.

What are the downsides?

As with everything, there are sponsors and detractors for any given approach. The main argument against having humans perform too many verifications is obviously speed; human interactions introduce latency and throughput limits to processes that may not necessarily be critical, and of course, all the costs associated with training people to verify the work accordingly. A deeper critique of HITL is that humans may fall into the illusion of accountability, overtrusting the AI and doing a bad job at the verification, falling into the comfortable assumption that the AI is mostly right for processes that should not tolerate negligent mistakes, as well as omission errors by failing to notice errors that the system doesn’t flag.

These dynamics may mean that simply adding a human won’t guarantee that the outcomes are better, since even highly skilled people can make mistakes. Additionally, some processes are inherently complex, and the human may just not understand the process enough to be able to meaningfully intervene.

Where do we go from here?

Our 25 years of experience with public sector digital development has us thinking particularly about how public sector agencies will navigate this new age, in particular, how they can develop, adopt, and scale AI that includes HITL. Additionally, as outlined in our thinking here, we are building an assessment technology in Jordan to frame AI responsibly, with human-in-the-loop in mind, to demystify how AI can be practically integrated into national systems to drive development outcomes.

Based on our prior experience, we’re looking at the age of AI and what needs to be cleared for adoption:

- Thinking through use cases and evaluating technology against use cases

- Licensing and how data is going to be used

- For Low- and Middle-Income Countries (LMICs), what downstream delivery bottlenecks need to be addressed?

Internally, we’re also thinking through AI and its impact on the humans, our software developers, within the software cycle. We think the impact of AI on the software engineering field is a bellwether for how we should collectively think about its impact on labor, development, and growth. Watch this space for how we talk about this in the coming months.

—

AI and Human-in-the-loop together improve quality, ethics, and trust only when humans have time, context, and authority to disagree with the machine, and when processes are built to capture and learn from their feedback.

AI, as it is now, holds the promise of addressing several of our long-standing problems when developing software that’s sustainable, but at least for the time being, and unless a new breakthrough is achieved, humans will have to stay in the loop.

Data on Youth and Tobacco in Africa Program Enters Phase II

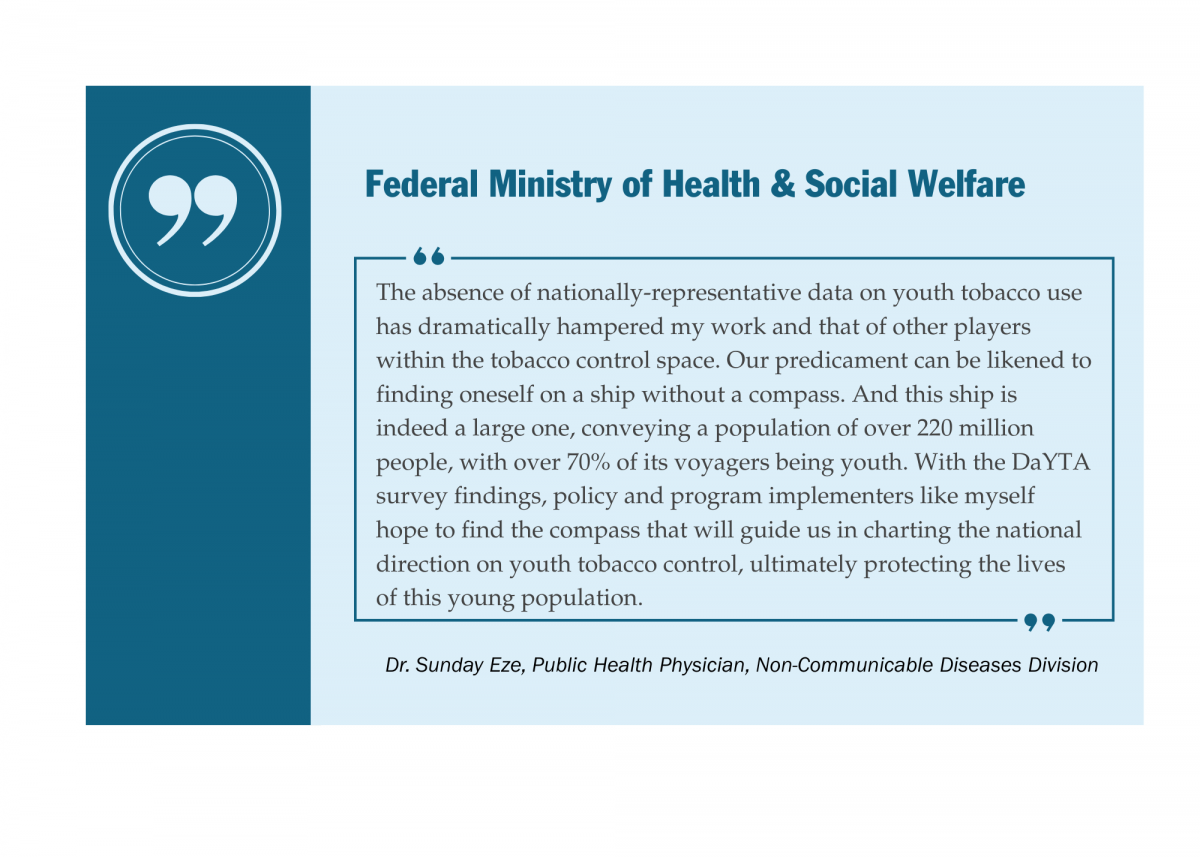

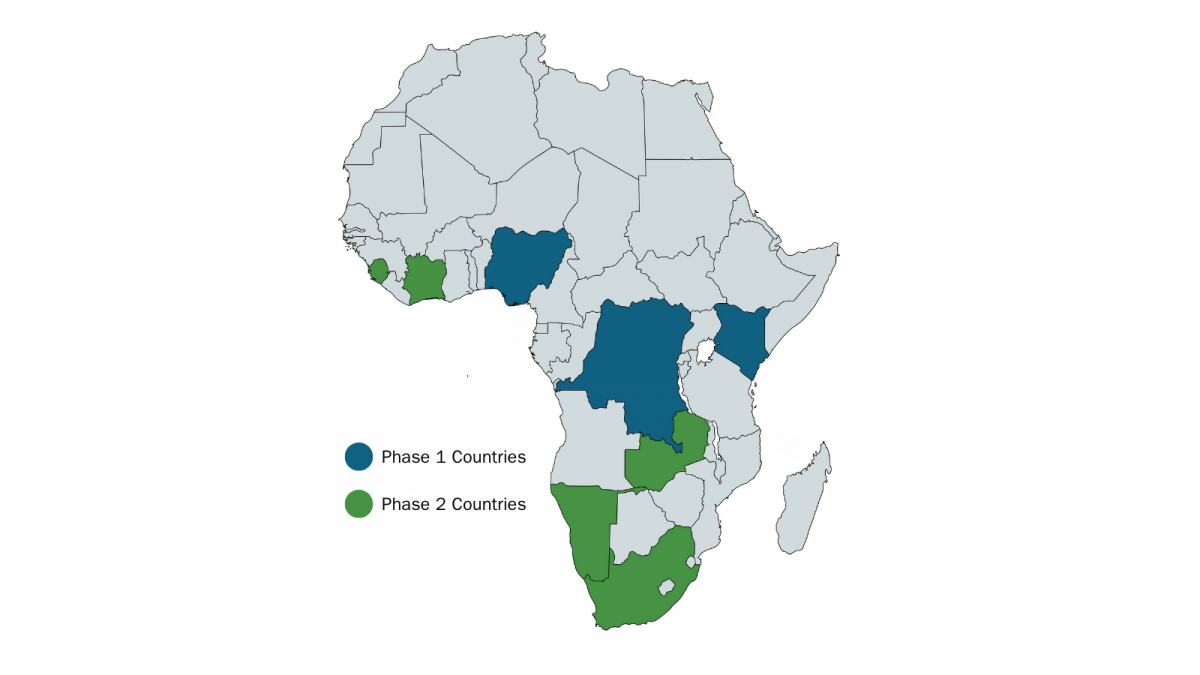

Launched in November 2022, DaYTA pioneered the first-ever nationally representative household surveys on tobacco and nicotine product use among adolescents aged 10–17 in the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC), Kenya, and Nigeria. These groundbreaking studies uncovered vital insights into adolescent tobacco use patterns, enabling policymakers, advocates, and researchers to better understand the risk this poses to Africa’s youth. The DaYTA program builds on the successes of the Tobacco Control Data Initiative (TCDI), where we partner with governments and civil society to collect, aggregate, analyze, and visualize existing and new tobacco control data. Utilizing country-specific platforms to present this data and to share the latest research and findings on tobacco control, TCDI websites have become trusted resources for policymakers, advocates, and researchers working to curb tobacco use.

Through TCDI, it became apparent there was a vast gap in data collected on youth tobacco use in Africa, which the DaYTA program has since been hard at work to fill. You can learn more about the data collection process of DaYTA’s first phase here, as well as check out the interactive TCDI portal here. In this blog, we’ll highlight DaYTA’s objectives, innovative approach, and the key activities we’re pursuing to drive impact in adolescent tobacco control measures across focus countries.

How DaYTA Transformed Adolescent Tobacco Data

Over the past three years, DaYTA has worked to ensure that data on adolescent tobacco and nicotine use in Africa is accurate and up-to-date. Prior to DaYTA’s inception, most available information on youth tobacco use in Africa came from school-based surveys conducted more than a decade ago. This resulted in major blind spots, including a lack of statistics on out-of-school adolescents, emerging nicotine products, and the rapidly shifting landscape of tobacco use across the continent. In our first phase, we broke new ground by conducting the first-ever nationally representative household survey on tobacco and nicotine use among adolescents aged 10-17 in the DRC, Kenya, and Nigeria. Across these three countries, we investigated key variables such as tobacco use prevalence and multi-level factors (e.g., individual- and household-level) associated with all forms of tobacco use, including smoked and smokeless tobacco products.

Our first phase of DaYTA delivered three major outputs: (i) country-specific research reports, (ii) a comparative analysis with its own report, and (iii) interactive Youth Prevalence pages hosted on the TCDI websites for DRC, Kenya, and Nigeria.

Added to this, three of our articles were published in peer-reviewed journals:

- Prevalence and determinants of tobacco use in 53 African countries: Evidence from the Global Youth Tobacco Survey (Addictive Behaviors Reports)

- Tobacco and nicotine product use among adolescents in Sub-Saharan Africa: protocol for a cross-sectional multi-country household survey (Frontiers in Public Health)

- What are the factors associated with alcohol, cigarette and marijuana use among adolescents in Africa? Evidence from the Global School-based Health Survey (British Medical Journal Open)

DaYTA’s approach distinguishes itself from other global adolescent tobacco surveys in three significant ways:

- Standardized yet locally rooted approach: Drawing on global best practices and existing surveys, we worked hand in hand with stakeholders from Ministries of Health, Education, and Youth, along with advocacy groups and adolescents themselves, to ensure the survey was both globally rigorous and locally relevant.

- Accurate mapping of the new and emerging tobacco landscape: Beyond traditional smoked tobacco products such as cigarettes, the survey included questions on the use of heated tobacco, e-cigarettes, and nicotine pouches – products that have never before been captured at a national scale in Africa. Given our exhaustive coverage of products, our data paints a fuller picture of youth tobacco use, filling notable gaps in existing datasets and answering governments’ most pressing questions.

- Broader reach of youth population: Unlike school-based surveys, our household-based approach reached both in- and out-of-school adolescents, who we have confirmed have the highest prevalence of tobacco use in all three countries surveyed. Our survey further included adolescents as young as 10 years old, expanding the age-range utilized by previous surveys.

DaYTA Phase 2

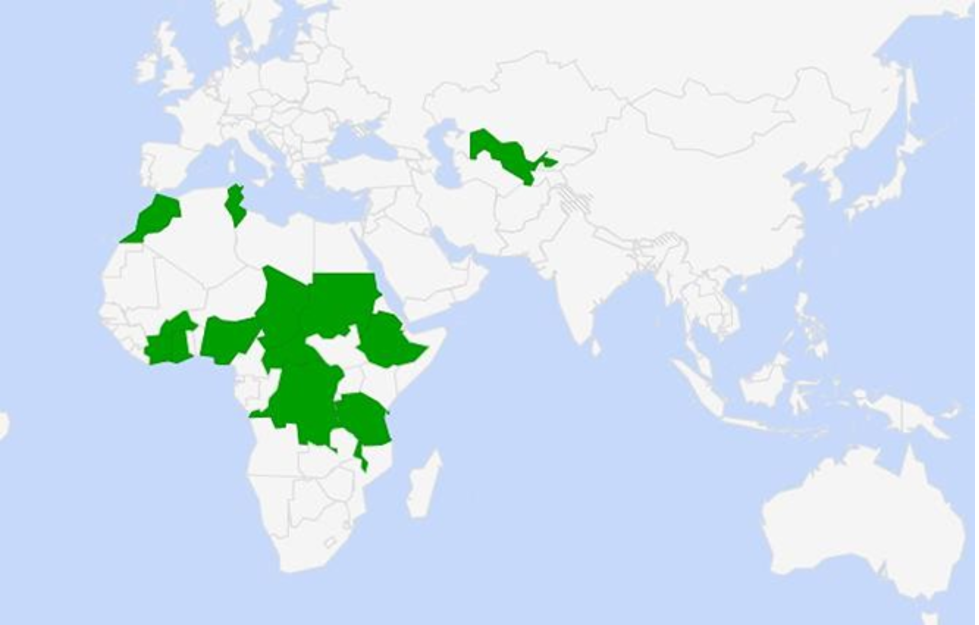

Following the strong reception of the DaYTA survey and growing demand from advocacy and policy groups, we are now launching the program’s second phase, expanding the approach to five additional countries: Côte d’Ivoire, Namibia, Sierra Leone, South Africa, and Zambia.

This second phase will focus on deepening engagement with key stakeholders – such as governments, research institutions, and youth advocates – to build trust and pinpoint remaining critical data gaps. Together, country teams will review the DaYTA methodology, confirm core questionnaire modules, and adapt optional modules to fit local contexts. Workshops will showcase how the survey addresses the identified data gaps, ensuring strong buy-in. In the first phase of DaYTA, the focus countries not only embraced the core content of the survey but also opted into all optional modules, underscoring enthusiasm for and broad support of the program. We hope to replicate this in future implementations as we expand to additional countries.

To ensure consistency across diverse settings, data collection will be conducted by local research firms, utilizing strengthened digital and quality assurance protocols, such as built-in digital checks coupled with independent review. This refined process will not only enhance data reliability but also enable meaningful cross-country comparisons and insights that connect and expand upon the findings from DaYTA’s initial phase.

When it comes to the dissemination of research, DaYTA’s findings won’t just sit in reports; they’ll be made accessible, visual, and actionable. We’ll share findings through the TCDI country websites, incorporating new youth-focused data and visualizations.

In the second phase of DaYTA, we will further build on the success of our pilot journalist training project, conducted in partnership with Nigerian NGO Renevlyn Development Initiative, and expand these activities to our additional focus countries. In the pilot, we provided training on tobacco control reporting to 20 DRC-based journalists, with the objective of equipping them with the skills to engage media outlets early, thereby speeding up the process of amplifying key findings. This will prove especially critical in countries with limited civil society presence, such as Namibia.

Harnessing AI

DaYTA’s second phase will also introduce a bold new AI workstream, aimed at exploring how artificial intelligence can be best used to transform our user experience, such as through engagement with new and existing dashboard content.

Through leveraging AI, we aim to make our tobacco control data more accessible, engaging, and actionable. Our objective is to co-design an AI-driven tool that draws on the expertise of tobacco control policymakers, researchers, advocates, and public health practitioners. By training the AI tool on this expertise and integrating it seamlessly into ongoing decision-making processes, we hope to create a solution that not only enhances usability and engagement but also addresses information overload as content grows. While we’re still in the preliminary design stages, our approach will mirror the rest of the program: high-quality, co-designed, and user-focused.

DaYTA’s Regional Leverage

As the influence from the tobacco industry increasingly crosses borders, regional alignment has become essential to closing policy gaps that weaken national tobacco control efforts. DaYTA’s geographic expansion and close integration with the TCDI make us uniquely positioned to drive impact beyond individual countries, thereby strengthening tobacco control across Africa’s Regional Economic Communities (RECs). With implementation spanning the Western, Southern, and Eastern African RECs and beyond, DaYTA and TCDI together form a robust regional evidence network. Their shared evidence base and comparable methodologies create a foundation for harmonized policy dialogue, enabling stakeholders to identify cross-border trends, align regulations, and address shared challenges such as illicit trade, youth access, and new and emerging tobacco and nicotine products.

For DaYTA Phase 1 countries (Kenya, DRC, and Nigeria), we envision our data and survey findings being actively used to improve national enforcement efforts that deter youth initiation and ultimately prevent tobacco-related illness and death. Although all countries prohibit the sale of tobacco to minors, adolescents continue to access these products with ease. While specific enforcement barriers vary by context – from retailer non-compliance and informal markets to gaps in community-level monitoring and limited cessation support for young people – these differences underscore the value of DaYTA’s comparable, cross-country evidence that sheds light on country-specific implementation gaps. Our stakeholders have also emphasized the need for cessation programs designed specifically for young people, reinforcing the demand for coordinated, evidence-based interventions.

By engaging government, civil society, and advocacy partners across multiple RECs, Development Gateway aims to translate DaYTA’s insights into regionally coherent strategies that strengthen health governance and protect young people from tobacco harms. In doing so, DaYTA moves from generating national data to shaping a coordinated regional response, transforming evidence into a catalyst for systems change across the continent.

Stay tuned for more about DaYTA’s second phase!

Interoperability as a Cornerstone of Resilient Digital Systems

How many apps do you have sitting unused on your phone – once downloaded to meet an urgent need but since then left unused? If you needed them again, would you even remember they were there?

Now, imagine your phone is a government system, and those apps are digital solutions meant to address public service challenges. Over time, as more platforms, dashboards, and tools are introduced, they pile up in silos: disconnected, hard to navigate, and ultimately less effective at delivering long-term impact for the people they were designed to serve.

Governments, the private sector, and NGOs have more digital tools and data at their fingertips than ever before, yet much of it remains untapped, underutilized, or completely unused. Trapped in silos, these data cannot be effectively leveraged to drive evidence-based decision-making or improve public services. Beyond limiting the sustainable impact of these solutions, siloed systems also hinder AI readiness and reduce the value data could add to digital public infrastructure (DPI) – both of which depend on interoperability and open data flows to achieve digital transformation.

At Development Gateway: An IREX Venture (DG), interoperability is central to how we approach digital transformation and design solutions that remain useful and usable long after the lifecycle of a program. In this blog, we unpack what interoperability means to us, drawing on insights from our ‘a Livestock Information Vision for Ethiopia’ (aLIVE) program, before highlighting why interoperability is more needed than ever before.

Solving Data Silos in Africa: Insights from aLIVE

DG has a long history of developing and implementing interoperable digital solutions across a wide range of sectors in Africa. Drawing on Steele and Orrell’s 2017 definition of interoperability as “the ability to join-up data from different sources in a standardized and contextualized way,” we see it as the most effective pathway to transform siloed systems into integrated ecosystems while safeguarding data sovereignty and ensuring local ownership.

But solving data silos is not just a technical challenge. As we‘ve seen in Ethiopia through our aLIVE program, it requires building trust among stakeholders, aligning global best-practices with local priorities, and designing systems to last past a program’s lifecycle. In other words, interoperability is as much about people and processes as it is about technology.

Through aLIVE, we are working with Ethiopia’s Ministry of Agriculture to strengthen the country’s livestock data ecosystem. Rather than layering yet another digital tool on top of existing platforms, the program focuses on connecting what already exists; standardizing livestock data to ensure systems can “talk” to one another. This makes data more usable and timely, while simultaneously fostering a shift from fragmented reporting to collaborative, evidence-based planning and stronger service delivery.

Some key insights from aLIVE’s work in Ethiopia’s livestock sector include:

- Build trust first: Interoperability depends on collaboration, not just between different systems but among the people involved, too. By bringing government agencies and technical experts to the same table, aLIVE has opened a space for dialogue, transparency, and shared ownership of solutions.

- Prioritize the local context: While global standards provide guidance, they only succeed when rooted in local priorities. aLIVE’s co-design process ensures the digital solutions put forward are practical, relevant, and usable within Ethiopia’s unique context.

- Design for sustainability: Technology is only as strong as the ecosystem that supports it. By investing in capacity building – training system owners and data users on how to get the most out of the standardized livestock data – aLIVE is ensuring that the improvements in livestock data will outlast the program itself.

Together, these insights show that interoperability is not only about connecting technical systems, but also about empowering the people and processes behind them to work toward achieving shared goals. By embedding trust, local ownership, and sustainability into its design, aLIVE demonstrates how data silos can be transformed into interoperable ecosystems that strengthen decision-making, improve service delivery, and prepare systems for the future.

It is through ensuring that systems are future-ready that interoperability further sets in place the foundations for AI readiness. With interoperable livestock data, Ethiopia can harness AI tools to predict disease outbreaks, improve food security, and strengthen climate resilience. And because livestock data connects to wider systems – trade, public health, environmental management, and economic planning – it becomes part of the country’s broader digital public infrastructure (DPI). In this way, aLIVE is not only transforming Ethiopia’s livestock data systems but also contributing to a stronger, more resilient digital foundation for the country as a whole.

Why Interoperability is More Needed Than Ever Before

The funding freeze from USAID and other US government agencies in early 2025 sent shockwaves through the international development sector. Its immediate effects were devastating: 34,880 metric tons of emergency food aid bound for Ethiopia sat rotting in shipping containers off the coast of Djibouti, while more than 20 million people worldwide lost access to life-saving HIV treatment and services.

But beyond these visible crises, the longer-term systemic consequences may prove just as damaging. The sudden halt of humanitarian projects destabilized fragile data ecosystems, disrupted data collection efforts, and undermined many of the digital systems that governments and NGOs rely on to deliver essential services. While less headline-grabbing than the rotting of emergency food aid or interruptions to lifesaving treatments, the erosion of data for service delivery is a hidden systemic crisis – one with the potential to weaken development and humanitarian efforts for years to come.

This moment underscores why interoperability is more important than ever. As aLIVE demonstrates in Ethiopia, interoperable data systems are not just about connecting platforms, but about ensuring that countries can build resilience, harness AI, and extend the value of their data across multiple sectors. In the face of funding volatility, interoperability becomes a safeguard against systemic fragility, helping countries sustain service delivery even when donor support diminishes.

Disruption also creates opportunity. The withdrawal of funding has highlighted the need to move away from historic overreliance on external funding toward more country-led, localized, and whole-of-system approaches. As our CEO, Josh Powell, along with the CEO of Results for Development, Gina Lagomarsino, and the former CEO of Global Partnership for Sustainable Development Data, Claire Melamed, wrote in a recent blog on the data crisis following USAID’s withdrawal, interoperability can be a powerful vehicle for achieving this form of digital transformation.

At this moment of uncertainty for the international development sector, interoperability should not be an afterthought, but a cornerstone for ensuring digital resilience. By enabling open data flows, strengthening local ownership, and embedding sustainability into design, it offers a path for countries to withstand funding shocks, protect sovereignty, and drive long-term digital transformation.

***

Read our white paper titled ‘Demystifying Interoperability, which discusses in practical terms what goes into implementing interoperable solutions in partnership with public administrations.

Why Africa Will Define the Next Decade of Digital Public Infrastructure

A reflection by three DG colleagues across country implementation, partnerships, AI, Data Governance and Strategic Communications

The conversation on Digital Public Infrastructure (DPI) is moving fast, and this was clear during the three-day Global DPI Summit in Capetown, South Africa, in November 2025. The vision was bold: a future where identity, payments, and data exchanges unlock development at scale. As highlighted by the CEO of Ekstep, Shankar Maruwada, during one of the side events on AI and DPI at the Summit, language is powerful, and shared vocabulary across stakeholders ensures alignment among technologists, policymakers, implementers, and funders. This is most visible with the DPI conversation, where language adoption has brought together various stakeholders at the global level, and the narrative is now shifting from high-level frameworks to one where countries are now looking at tools, governance models, and partnerships that support actual service delivery.

While the energy now feels different with this Summit, we also sensed a growing tension. DPI is gaining endorsement from governments, philanthropists, multilaterals, and private-sector actors, but remains deeply complex. As colleagues based in Africa and working across different countries, in digital transformation, data governance, AI, interoperability, partnerships, policy, and communication, this is the space where we have quietly been working for years. This piece reflects what resonated, what challenged us, and where we think the conversation must go next.

1. The Conversation Has Shifted: From Idealism to Implementation Reality

From the Summit, it was clear that there was a sense of urgency to move towards implementation and ensure that DPI works for countries and serves citizens. Panel discussions showcased country examples but also asked difficult questions: how do we finance and maintain DPI sustainability? How do we move fast and avoid vendor lock-in? How do we ensure interoperability?

The 50-in-5 Campaign is growing and is now in 32 countries. We saw concrete commitments such as the 10-year Public Private Partnership (PPP) model (Palestine) and production-grade systems replacing pilots. This symbolizes a collective appetite towards implementing DPI and making it work. The conversation on implementation also brought in the messier reality of implementing DPI, moving us away from concepts and rhetoric. Political transitions, capacity (not only technical but strategic), ethics, and culture shape what is possible. This on-the-ground reality is where African experiences matter, as it brings a valuable realism to the global conversation and highlights the trade-offs that must be clear.

2. Trust and Inclusion: The Backbone of DPI

If there is one theme that came up in every session, it was trust. It was highlighted as a core building block to ensure that digital systems survive political cycles and earn public buy-in. The trust conversation was framed through various lenses at the summit – procedural (focusing on safeguards and regulation), operational (systems that work), and relational (where citizens believe the services provided will benefit them). A panelist from Kenya gave an example that illustrates this point: his 18-year-old son completed 80% of passport processing online using the eCitizen (a portal for government information and services), only to repeat biometric steps that he had completed for his national ID. This raises the question: why isn’t data that has already been collected used to improve service delivery? This is both a technical question on interoperability, but also a question of institutional trust and people’s risk comfort.

In Africa, perspectives on trust are especially important. This Research ICT Africa project highlights that DPI in African countries cannot be copied from other regions and cannot be separated from issues such as uneven access. Trust building must begin with understanding these realities.

3. Interoperability is Non-Negotiable but is Still Poorly Understood

It was great to finally see interoperability discussed as a non-negotiable, not a nice-to-have. This helps with making DPI more valuable. We heard examples of this in practice, such as the Inter American Development Bank’s tech platform, which supports digital integration across Latin America and the Caribbean by allowing citizens to access digital services with a single account across multiple platforms and countries. Similarly, the Government of Indonesia shared insights from its Government Services Liaison System, which is designed with auto-scaling capabilities. This allows the system to automatically increase capacity during spikes in demand, such as during the rollout of large public programs. As the country’s Director of Digital Government Application, Yessi Arnaz Ferrari noted, “This is exactly what allows us to grow from 65 agencies to 435 connected institutions, handle over 58 million data transactions this year, and still maintain about 99.9% uptime.”

Despite this, we noticed that many DPI initiatives shared as examples in the summit focused on digital ID and payments, and they are seen as more fundable and politically attractive. Data exchange remains the missing middle and is challenging to achieve. An example from Burundi on a data exchange system deployment highlighted issues around language barriers: French as the main platform language and local languages lacking technical terms, access limitation with only 40% of the population having smartphones, and some local offices hesitant to participate in integration across registries. We know from DG’s experience helping governments repurpose legacy systems, share data assets, and build data exchange mechanisms fit for interoperability that this invisible area is both hard to achieve and will be essential for DPI going forward.

Where does the conversation go from here, and what must the Global community learn?

As the global DPI movement moves from ‘what’ to ‘how’ and enters an operational decade, African experiences will determine what this decade looks like. As Dr James Mwangi, CEO of Equity Bank, noted at the Summit, Africa’s current 2-3% GDP contribution, despite accounting for 18% population share, is not a deficit but evidence of massive untapped potential that private sector-led DPI can unlock. He argued that Africa’s underdevelopment makes it the world’s biggest growth opportunity and emphasized that African capital must be deployed by Africans for African infrastructure rather than relying on grants and philanthropy. Most critically, he reminded the audience that by 2050, Africa will hold 42% of the world’s labour force, 2.6 billion people with a mean age of 18, and that with the right DPI foundation, this workforce can serve global markets from Africa, flipping the prevailing narrative on migration and dependency.

In our internal reflections, one analogy that sparked discussion was viewing DPI as a public good – similar to roads. The comparison helped us to surface questions about who funds, builds, governs, and coordinates systems so they serve the public interest. While real-world arrangements are often far messier and differ depending on context, the analogy was useful in highlighting risks around fragmentation and misalignment when coordination is weak.

Against this backdrop, DPI will not succeed in Africa on advocacy and branding alone. The continent will test assumptions, reveal blind spots, and ensure that innovation is practical and works for the people it aims to serve.

Notably, civil society voices were largely missing from the conversation. While some Open Government Partnership colleagues were part of the discussions, there is a need for more civil society and a wider range of government actors in this space as well. The narrative on speed, with some voices missing, risks overshadowing institutional readiness and leaving DPI deepening digital inequalities in countries, working to the disadvantage of the marginalised communities it also seeks to benefit.

The campaign may be ahead of the evidence around economic value and socio-technical realities, but research projects such as this by Research ICT Africa will ensure that DPI in Africa is grounded in real political economies and institutional incentives and works for the people it serves. This moves the conversation to the next stage, stepping away from “how do countries adopt existing DPI models” to “what does DPI need to succeed in African countries”? Communities of Practice and Informal Networks, such as ImNet hosted by Open Cities Lab, bringing together African DPI implementers, will ensure a coordinated approach amongst DPI implementers in support of inclusive economic opportunity, digital sovereignty, and improved public service delivery.

The global community has started to listen, and the continent’s realities on access, linguistic diversity, informal economies, and affordability challenges will bring clarity that global frameworks often overlook. On that front, Africa will define DPI on its own terms and show the world the way forward.

Building Useful & Usable AI: A New Tool to Curb Procurement Corruption

Public procurement accounts for one-third of government spending across the globe, totaling around 10 trillion dollars a year. Despite producing millions of pages of procurement data annually, governments make the vast majority of this information either inaccessible to the public or available in formats that make it hard to extract meaningful insights on government spending. Only 2.8% of public procurement documents are published as open data, with significantly less published in a format that would allow journalists, civil society, or the private sector to flag potential cases of corruption.

Given the sheer volume of transactions that take place globally, large sums of money involved, complexity of the process, and the close interaction between public officials and businesses, public procurement is particularly vulnerable to malign acts. Globally, an estimated 20-25% of government spending on public contracts falls prey to corruption, with this percentage rising to 50% or higher in certain regions. One of the enablers is the lack of transparent processes and accessible data.

As such, the HackCorruption program – a collaboration between Accountability Lab and Development Gateway: An IREX Venture (DG) – has developed a new contract summary and analysis tool powered by artificial intelligence (AI) that has been submitted for registration as a Digital Public Good (DPG).

See the GitHub page below for documentation: https://devgateway.github.io/automatic-contract-summarizer-portal/

Powered by a large language model (LLM) to extract important information from lengthy government contracts, the tool enables easier flagging of corruption risks – allowing users to analyze and summarize thousands of documents in hours with minimal human intervention. By automating the data analysis process and highlighting trends in the often opaque procedures of public procurement, it provides users with the timely, accessible data required to strengthen transparency and ensure good governance in public contracting.

Identifying The Core Challenge

The idea for this AI tool came from the lessons learned and insights gained during the regional hackathons organized through the HackCorruption program. While working alongside the winning teams from HackCorruption Latin American in Colombia, it became apparent that many were struggling with a similar challenge: how to efficiently and effectively process public procurement contracts. The need for such a tool was further highlighted during HackCorruption South-East Asia. Once again, teams expressed the same desire to process contracts without the significant time and cost of human intervention.

Manually reviewing these lengthy contracts is a slow, costly, and ineffective process. Extracting important information from contract documents – such as names, amounts, durations, a list of goods and services requested and provided, and so on – requires a significant amount of time and effort for a human to complete. However, with the help of AI technology, this process can be completed in a matter of hours or days at most.

Drawing on the experiences of these hackathon teams, the HackCorruption team began work on creating a tool that could be used to streamline the process of analyzing large numbers of contracts to ensure a more efficient method for identifying corruption risks.

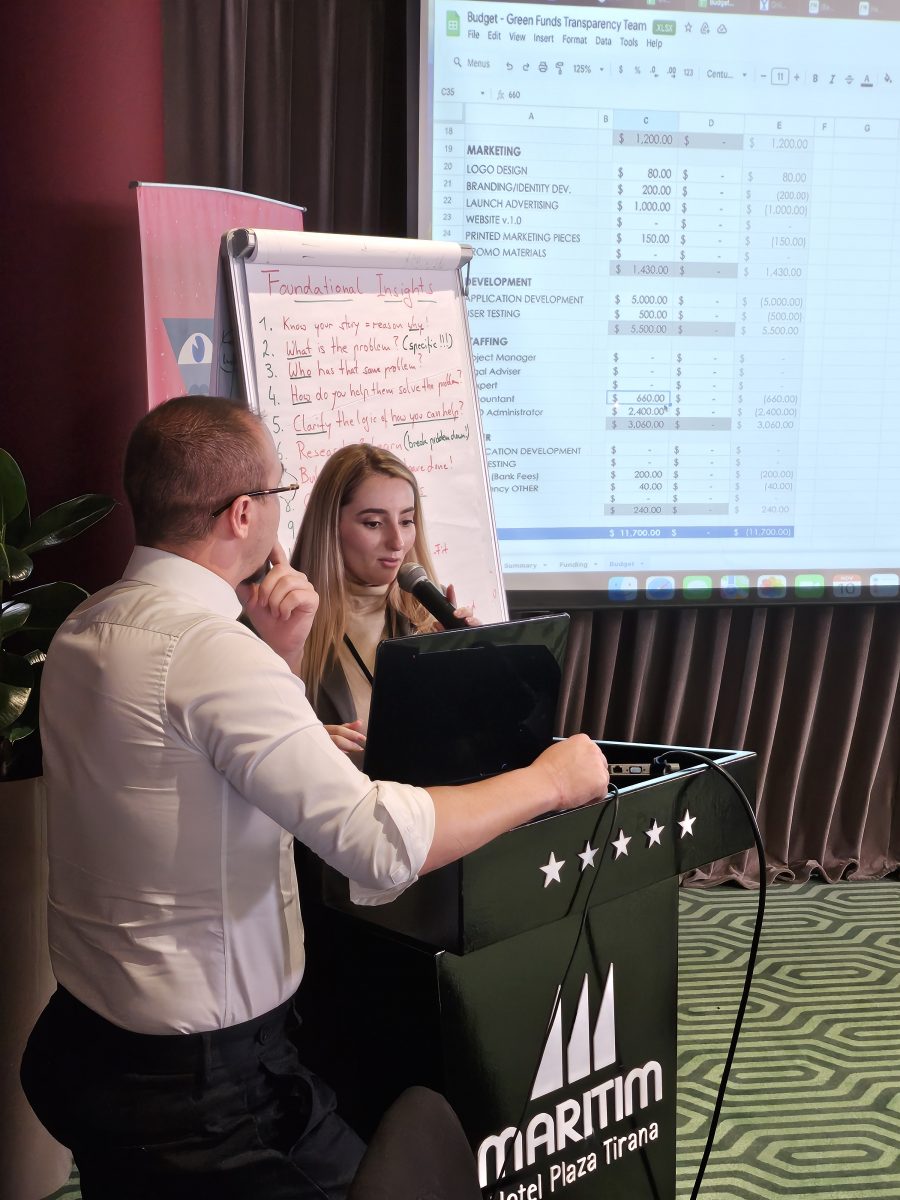

Using AI to Untangle Opacity in Green Funds: A Case Study From HackCorruption Balkans

Green Funds Transparency was one winning hackathon teams that particularly struggled with getting the contract data that they needed for their tool, a website that focused on two interconnected challenges:

- The lack of transparency in the allocation and use of green funds: These contracts, which include funds for climate resilience and environmental infrastructure, often pass through a complex system of procurement channels. This means the documentation is prone to becoming fragmented, inconsistent, and difficult to audit.

The broader issue of procurement opacity: Government contracts are lengthy documents that are, for the most part, poorly structured. This makes them difficult to analyze and search through, decreasing the ability to detect irregularities or patterns that could indicate corruption or mismanagement.

As they began to develop their tool, the Green Funds Transparency team relied on the manual review of procurement documents, donor reports, and government disclosures. This was a slow, labor-intensive process and, due to inconsistent formats and limited access to source data, often resulted in an incomplete analysis. Further complicating matters was the fact that many of the contracts they needed to review were not machine-readable, making it almost impossible to cross-reference them with environmental impact metrics or financial flows.

The team believes that an AI tool that can extract structured data from unstructured contract documents would be transformative.

“The tool could help track fund flows, identify discrepancies, and flag contracts that lack environmental safeguards or performance indicators. It would also allow for real-time monitoring, pattern recognition across large datasets, and proactive identification of red flags – empowering oversight institutions, civil society, and journalists to act on credible insights rather than anecdotal suspicions,” he adds.

While beneficial, it is vital to also take into account safety and ethical considerations that accompany the use of AI for such purposes. This includes ensuring that the methodology for training the AI is transparent and that the data it is trained on doesn’t reinforce biases in historical funding practices. According to Green Funds Transparency, these safeguards should include:

- Human oversight in interpreting outputs

- Clear documentation of training data

- Protection of sensitive data

- Mechanisms for correcting errors or misclassifications

- The responsible use of predictive analytics to avoid false positives

With the right safeguards in place, AI and the specific tools we create using it have the ability to fundamentally change the way we analyze vast amounts of data, as well as to vastly reduce the amount of money, time, and effort required to do so. Such tools can enable a small team or even an individual reporter to more accurately identify corruption risks in government contracts, empowering them to enforce greater levels of transparency, more accountability, and, ultimately, enhance good governance in their specific sector.

Building useful and usable AI based on actual needs

The idea for this AI tool came from the lessons learned and insights gained from the HackCorruption project. While working alongside the winning teams from HackCorruption Latin American in Colombia, it became apparent that many were struggling with a similar challenge: how to efficiently and effectively process public procurement contracts. The need for such a tool was further highlighted during HackCorruption South-East Asia. Once again, teams raised the same desire to process contracts without the huge amount of time and cost of human intervention required to do so.

Drawing on the experiences of these hackathon teams, the HackCorruption team began work on creating a tool that could be used to streamline the process of analyzing large numbers of contracts to ensure a more efficient method for identifying corruption risks.

After assessing the needs of several HackCorruption teams, such as Green Funds Transparency, plans were put in place for the creation of an AI model that could be used to extract or summarize information in contracts of any size (from a few Kilobytes to Megabytes) in either pdf or doc.x formats. While initially focused on contracts written in English, this tool will support additional languages in the future. The final requirement – and one placed as the top priority for success – was that this AI model should be free to use and able to be run either in the Cloud or on local computer systems using consumer-grade GPUs – meaning that the tool can be used without needing to spend thousands of dollars on expensive equipment.

Designing the tool to operate within these parameters ensures that it can serve anyone who is interested – including those from journalism, academia, or NGOs. By assisting users to extract relevant information from contracts that exist only as pdf/MS Word documents and whose information cannot be easily accessed from a database or in a standardized format such as the Open Contracting Data Standards (OCDS), this AI tool makes it possible for those working on anti-corruption to do their work more easily and faster than ever before.

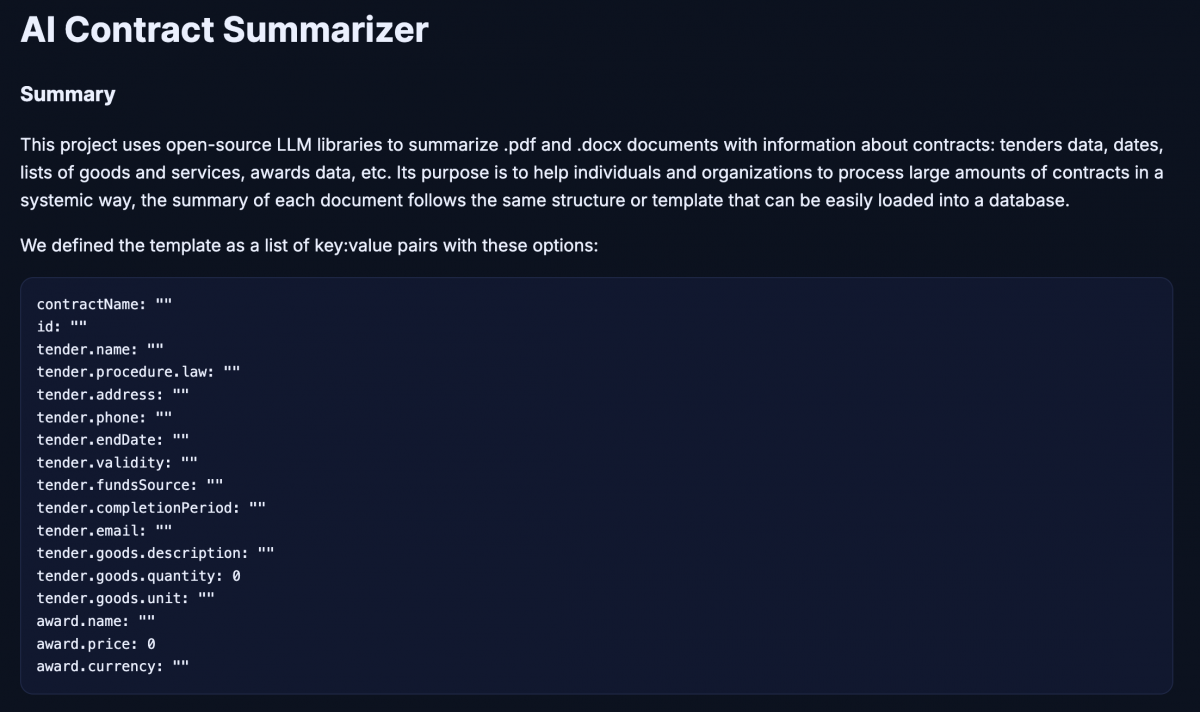

Training AI to understand and extract meaning from public contracts

HackCorruption’s AI model is designed to read documents from a directory one by one and generate a text file that follows a predetermined format that contains all relevant information extracted. This includes the contract ID, contract name, implementation dates, lists of goods and services, and so on. There were two different phases required to create this tool:

- Training: The first task was to select a small randomized subset of documents and train the LLM model so that it could learn to recognize and extract important information and generate the analysis in the desired output format. We generated results that were clear, valid, and cohesive with a subset of around 100 contracts. The training methodology we used was supervised training, where each contract was paired with a human-written summary. The model used this to “learn” how to process new documents with a similar format/layout and then produce summaries similar to the example provided. The structure used in the summary documents is below.

2. Data Extraction: Once the LLM had been trained and there was minimal error detected in its analysis of the documents, then it was used to extract information from all of the remaining documents. While the tool can assist in extracting useful information from contracts, it is important to recognize that some cases may require additional manual checks. The source code comes equipped with guidelines on how to set the tool up and begin using it for data extraction, and is structured in such a way as to be easily upgraded with future AI models.

3. Data Quality: Once the AI tool summarizes each contract, it applies a series of post-processes aimed at minimizing the possibility of hallucinations.

Lessons Learned & Recommendations

We developed the tool through listening and learning from HackCorruption teams from different regions. And yet, that was only the beginning of the learning journey. Here are three lessons we learned while conceptualizing and creating this AI tool:

-

- Cloud is better, but local still works: Having access to cloud resources can help you speed up the training process, but it is not mandatory – you can still use your pc/laptop and obtain good results.

- Flexibility and adaptability are key: AI is an evolving area with new LLMs, tools, and free libraries appearing almost every week. As such, it is paramount to keep well-informed and to ensure that the source code written for these new tools can be easily upgraded to ensure they don’t quickly become outdated.

Learn from others: As all those involved in HackCorruption over the past three years know, collaboration is the key to success. There is a huge community of developers and researchers who offer their code examples, tools, and experience for free. Learn from them and see what you can incorporate into your own projects.

While this is an ongoing project and there will be many more lessons to learn as we progress, there are two recommendations that we have identified to date that can help potential users and developers looking to utilize AI to its fullest potential:

- Invest some time to learn the basics of how AI really works. You don’t need to read all the papers nor understand all the math or coding behind it, but, as with everything, the better you understand the basics, the more likely you are to use the tool effectively.

- It’s important to keep in mind that not all libraries are open source, especially those for processing pdf files. As such, it may take time to change the code later if a library substitution is needed.

With our application submitted for this AI Contract Summarizer tool to be registered as a Digital Public Good (DPG), it will soon be available for use by all working to curb corruption in public procurement. Keep an eye out for a follow-up blog that announces the tool’s successful registration as a DPG!

Accelerating Institutions: How DG’s 25 Years Create Unique Value for AI

As we celebrate 25 years of DG’s efforts supporting institutions to use digital and data to accelerate and amplify their impact, governments, companies, organizations, and people globally are grappling with how to invest in AI tools with this same goal in mind. Technology is evolving rapidly, the hype cycle is overwhelming, and many implementations are falling short of their intended value.

Often, as any good technologist will likely tell you, the technology is the easy part, and failure lies in a combination of design, process, capacity, and commitment. The next few years will require thoughtful and adaptive efforts to rightsize and rework AI implementations that create real value and impact in the lives of students, smallholder farmers, patients, and others who rely on them.

At DG, our engagement with AI follows the same use case-driven, complexity-respecting capabilities and methods that we have used for decades:

- We look beyond hype to identify and drive genuine value. Our processes begin with understanding people’s missions, capacity, and objectives, distilled into use cases and problem definitions that ensure that institutional solutions are both grounded in context and truly impactful for our partners.

- We have a deep understanding of working with governments and their existing technology ecosystem. Effective AI solutions rely upon high-quality, accessible, and well-governed data. We have decades of experience supporting staff across levels in government ministries – and other large institutions – in assessing, updating, and making interoperable their existing ecosystem of legacy data systems. The correct combination of technical, political, analytical, and change management skills needed for this work is invaluable (and rare) in positioning Low- and Middle-Income Countries (LMIC) public sector institutions to meaningfully adopt and use AI to become more effective.

- We are impartial and outcome-oriented. DG is a technology-agnostic organization. When appropriate, we prioritize using open-source tools that prevent vendor lock-in and preserve flexibility. We open-source our own technology and have registered multiple Digital Public Goods. Governments, organizations, and other institutions may have existing agreements with technology vendors, and we are comfortable evaluating and working with proprietary software. This flexibility allows us to effectively act as a trusted advisor for leaders choosing among a rapidly changing array of possible AI applications, rather than a vendor for any single product.

- We balance ethics, sustainability, and pragmatism. Our partners operate in complex environments with complex challenges. We do not believe that technology can solve every problem, and it must be paired with the right intentions and processes. Flexibility, compromise, and attention to long-term sustainability are key to successful digital transformation and resilience.

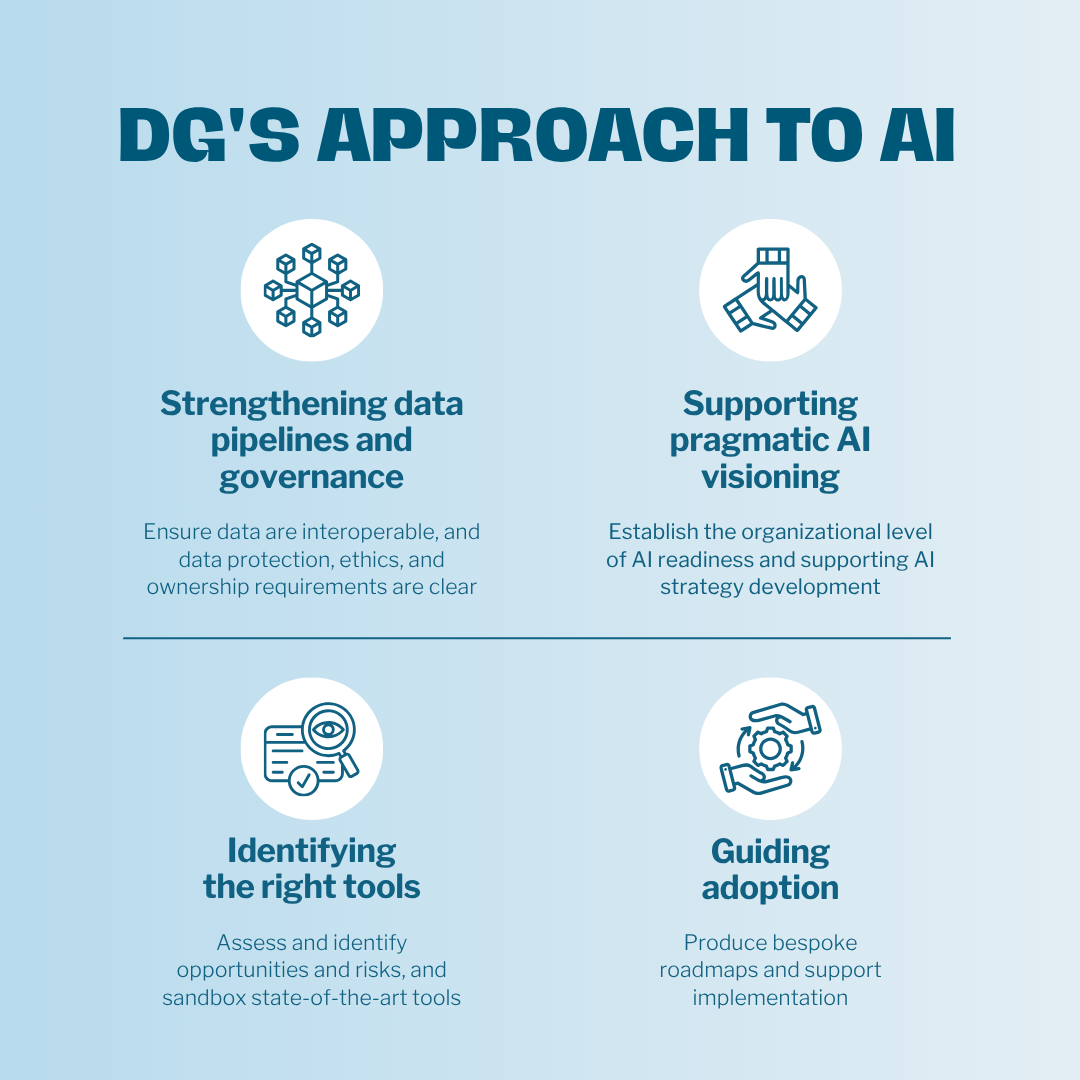

With these principles in mind, DG is engaging in AI through four pillars:

- Strengthening data pipelines and governance

For decades, DG has delivered systems interoperability and strengthened data pipelines, helping institutions maximize their data systems. Our Aid Management Program (AMP), for example, launched twenty years ago with the belief that standardized aid data could strengthen country ownership of the development process and align aid with national priorities.

We’ve also shared insights from transforming Ethiopia’s livestock data systems into a resilient, interoperable data ecosystem and have informed best practices in data governance across health, agriculture, and other sectors from the farm level to cross-border contexts.

Grounded in this expertise, we will continue to enable the flow of interoperable data, establish governance protocols, unlock inter-institutional data sharing, promote privacy, and center ethical considerations that bolster successful AI readiness and responsible adoption.

- Supporting Pragmatic AI Visioning

DG applies our technology-agnostic approach to define use case-driven requirements for AI and assess potential solutions. Through a co-design process, we work with stakeholders to identify use cases and existing workflows before developing technical requirements and solutions.

This same approach guides our assessment of organizational AI readiness and informs our development of AI strategies and roadmaps. Our visioning takes factors such as existing digital infrastructure, technology policies, and personnel capacity into consideration, balancing ambition and pragmatism. This approach allows for AI strategies that are context-driven and fit for the future. Through the Early Grades Education Activity [Asas for short], led by IREX in Jordan, we are supporting the development of a new AI strategy for the Ministry of Education.

- Identifying and Sandboxing the Right Tools

Landscaping – DG’s experienced software development team and history of translating global best practices into local solutions position us well to support the execution of AI visions. Once use cases for AI are established and prioritized, in turn creating a decision framework, we can systematically scan the fast-changing landscape of AI projects, software tools, and services that could potentially meet stakeholder and institutional needs.

Our evaluation framework considers not only the technical capability, interoperability, and scalability, but also sustainability factors such as licensing models, energy efficiency, portability, and policy alignment (i.e., data sovereignty regulations in country). We also assess local and regional AI efforts. This landscaping clarifies which tools merit deeper exploration for next steps and highlights the risks and limitations of potential solutions.

Sandboxing – When appropriate, DG can develop a controlled environment, known as an AI Sandbox, for safe experimentation and red teaming. Open-source solutions can be directly deployed in our sandbox, while proprietary tools will be evaluated via structured demos and reviews with prospective vendors. We capture metrics–such as potential efficiency gains, accuracy and reliability, governance alignment, user experience, and total cost of ownership–that will inform if and how specific tools can be taken further. This hands-on exploration enables stakeholders to see how tools perform against real requirements and builds a tangible foundation for decision-making for leaders in the changing AI space.

- Guiding Adoption and Scale

Institutions worldwide are grappling with how AI pilots will scale. Whether we are analyzing the results of the landscaping and sandboxing or partnering with a government that has already deployed solutions, we guide further adoption and scale.

This pillar of engagement includes both technical development, accompaniment of enterprise adoption, and recalibrating AI roadmaps into actionable plans for scale, incorporating recommendations on what should be adopted, adapted, and avoided. Recommendations can also incorporate standards for software, hardware, data standards, ethical safeguards, sustainable development, and capacity-building programs, all of which improve the chances of long-term sustainability of systems.

Technology Changes, Institutional Use Stays (Largely) the Same

Remarkably, while AI is potentially revolutionary and transformational, our methods for engaging with it remain within DG’s standard principles and approaches. Our partnership with IREX embodies this ethos, combining DG’s data systems and governance expertise with IREX’s institutional performance leadership to help civil society and government partners responsibly unlock AI’s potential. The technology may be new, yet ensuring we are context-driven, ethically grounded, and sustainability-focused has been DG’s ethos for decades.

Excitingly, we are already engaging with AI through our partnership with IREX and in other work across sectors and borders. Looking forward, these areas of focus will guide our support to partners across our priority sectors: education, agriculture, health, and governance.

Reflecting on 3 Years of Digital Advisory Support for Agricultural Transformation

Building resilient food systems is essential to ensuring global access to nutritious, sustainable diets. Yet, despite agriculture and food production increasing globally over recent decades, acute food insecurity and malnutrition continue to rise, particularly among the world’s most vulnerable populations.

Addressing this challenge requires systemic change across the entire food ecosystem, from production and monitoring to distribution and quality assurance. It also involves equipping smallholder farmers with timely data and user-friendly digital tools that empower them to make informed decisions, improve productivity, better integrate into existing value chains, and deal with the interconnected challenges they face.

However, merely supplying data and digital agriculture tools is insufficient to enable the systemic change required to strengthen the resilience of food systems. To achieve this form of long-term impact, it is necessary to provide sufficient advisory services on how to best utilize these data and tools, as well as local capacity building and training to ensure that the necessary advisory support services remain available when and where they are needed most.

DAS: Improving the Efficiency of Agriculture Data Use

To support this need, Development Gateway (DG), in partnership with digital development experts, Jengalab, and training experts, TechChange, with support from the International Fund for Agricultural Development (IFAD), implemented the Digital Advisory Support Services for Accelerated Rural Transformation (DAS) program from 2022 to 2025. By providing technical support for ICT4D activities within IFAD-financed programs, DAS aimed to improve the livelihoods of rural smallholder farmers through facilitating digital transformation in agriculture. The program’s target regions were East and Southern Africa, Central and West Africa, and the Near East and North Africa.

With the DAS program concluding in March 2025, we reflect on its impact in integrating ICT4D solutions to improve rural livelihoods, the effectiveness of its knowledge transfer and capacity building for sustaining gains, and the lessons it offers for future agricultural technology programs.

Integration of ICT4D Solutions

To support IFAD – the only multilateral development institution that focuses exclusively on transforming rural economies and food systems – with its digital strategy, DAS provided on-demand advisory services to support ICT4D activities for IFAD-financed programs. By filling gaps related to technical support, DAS strengthened the ability of these programs to build, maintain, and scale their use of technology in supporting farmers.

While the impact of the DAS support services is ongoing and may only become apparent in the months and years to come, some have already been identified, captured in the examples below.

Nigeria

In Nigeria, the DAS program conducted an assessment of the digital agriculture ecosystem. Serving as foundational research for various project activities – including online training on principles of digital development, interoperability, and in-person monitoring and evaluation (M&E) training – this assessment helped identify key digitalization challenges in the country, such as connectivity and affordability, and generated recommendations for strategic partnerships to address these challenges.

The assessment, which identified data gaps, prioritized interventions, and fostered collaboration with stakeholders, facilitated the development of an ICT4D strategy with the Nigerian government, laying a solid foundation for local ICT-enabled projects and providing a strong case for scaling digital innovations in IFAD-supported programs.

Morocco

In Morocco, DAS provided ICT4D support to the Integrated Rural Development Project of the Mountain Areas in the Oriental Region (PADERMO), contributing to the development of specific actions within the project. These included a pilot initiative to monitor beehives digitally, the establishment of digital agricultural cooperatives, and the use of digital services to promote and market agrifood products.

In particular, support from DAS partners enhanced the integration of digital tools, such as piezometers – geotechnical sensors that measure pore water pressure and water level in soil and rock – during the design phase. To further improve impact in future interventions, the team noted that digital skills training and a deeper understanding of implementation partners’ practical capacities would be highly beneficial.

Tanzania

In Tanzania, DAS assisted with the development of the country’s first e-agriculture strategy – the Digital Agriculture Strategy (2025 – 2030) – by conducting a situational analysis and generating a draft zero for it. This enabled the Ministry of Agriculture (MoA) to better leverage digital agriculture technologies and enhance data-driven decision-making in the country. DAS further supported capacity-building activities for the government and implementing partners on how to effectively integrate digital solutions for agriculture, informed by digitalization trends and practices from other countries.

Following the development of the e-agriculture strategy, IFAD, in collaboration with the United Nations Capital Development Fund (UNCDF) and the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO), formed the Joint Programme on Data for Digital Agricultural Transformation, supporting the MoA to better leverage data and strengthen interoperability to transform the country’s agriculture sector and provide more efficient service delivery. Through the technical support provided by DAS and the subsequent Joint Programme, 10 innovative agri-tech projects are expected to scale up, with additional catalytic investment provided for 3 agri-tech projects. It is estimated that this will result in more than 500,000 smallholder farmers – including 300,000 women and 100,000 youth – gaining access to enhanced digital services.

Impact of Capacity Building Trainings

By identifying specific learning areas within digital agriculture that would be of greatest relevance to IFAD-financed programs, Development Gateway and TechChange designed a number of training courses that provided capacity building for those who work in agriculture, as well as to mid-to-senior level officials and technical staff working in ministries, agencies, and organizations.

A total of 19 in-person training sessions were held on a variety of different topics, reaching 940 participants. Following up with these participants more than six months after they had completed their training, 92% stated that much or all of the course content remained relevant to their work and that they continue to frequently support colleagues using the concepts learned.

In addition to in-person training sessions, the DAS ICT4Ag Digital Classroom Series was created, containing four IFAD-sponsored self-paced training courses and ensuring the continued impact of the initiative. Two examples of IFAD-sponsored training courses on digital agriculture are highlighted below.

Basics of Digital Agriculture Ecosystems and Interoperability

In this course, participants learned about the causes and consequences of fragmented data, as well as the tools and techniques needed to achieve digital transformation for rural agriculture. Through exploring models of enabling environments for digital agriculture, participants learned how to assess the maturity of their own agriculture ecosystem. This course further outlines use cases and best practices for interoperable data use in digital agriculture, linking data from different sources in a standardized, context-aware way.

Access the free 2-hour self-paced Basics of Digital Agriculture Ecosystems and Interoperability course.

Basics of Digital Rural Finance for Agriculture

Introducing participants to digital finance in agriculture, this course explores how digital services and tools can be applied to an agricultural project or intervention with a financial component. Completing the course enabled participants to draw insights from IFAD’s project portfolio on the relevance of digital technologies to advance financial inclusion in rural areas, as well as to utilize IFAD’s financial strategy to deliver these tools and services to smallholder farmers.

It further equipped participants with knowledge of how to accurately assess the financial needs of smallholder farmers and how best to leverage digital technologies to address them. Through the use of real examples and case studies, the course made understanding the principles underlying the design and implementation of digital financial initiatives as simple and applicable as possible.

Access the free 2-hour self-paced Basics of Digital Rural Finance for Agriculture course.

Lessons Learned & Recommendations

Through its 3-year lifespan, the DAS program made significant strides in supporting the digital transformation of agricultural systems across IFAD’s portfolio across East and Southern Africa, Central and West Africa, and the Near East and North Africa. Through tailored advisory services, targeted capacity building, and the development of knowledge products, the programme strengthened the ability of governments, project teams, and implementing partners to integrate digital tools in a way that is inclusive, sustainable, and aligned with local contexts However, as with every program, there were lessons to be learned on how to improve the impact of such programs in the future.

- Deploying ICT4D solutions in resource-constrained settings with low levels of digital literacy requires a strategic, context-aware approach that grounds innovation in practicality.

- Time constraints were a recurring challenge in countries such as Tunisia and Uzbekistan, where short mission durations restricted the depth of engagement. This hindered the ability to address more complex digital needs or provide sufficient capacity-building.

- In scenarios where capacity is limited and advisory engagements are short, it can further be difficult for the Project Management Unit (PMU) staff to define their needs and internalize the steps necessary to drive change and sustainably take recommendations forward to achieve long-term success.

- Programs could have benefited from a more unified approach to digitalizing Monitoring & Evaluation (M&E) processes, as well as involving end users in the design of any tool.

- Although the DAS intervention has proved valuable in a multitude of implementing countries, room for improvement exists in tailoring the digital solutions provided to fit the local context. Feedback suggested that consultants could benefit from a deeper understanding of IFAD’s context and projects to enhance their ability to provide practical and implementable technical solutions. This is particularly important in aligning with the realities on the ground, such as the technical capacities of the implementing partners, the developmental (rather than research-oriented) nature of IFAD projects, and the characteristics of the final beneficiaries – mainly smallholder producers with relatively low digital and technical skills.

Recommendations for Future Programs

As the DAS program closes, it opens more doors for follow-up initiatives that build on the results it has achieved. In particular, the three facets of knowledge transfer, local ownership, and long-term sustainability will remain paramount for any initiative seeking to achieve digital transformation in the rural agriculture sector.

More than that, the following recommendations are suggested for future programs:

- Prioritize preliminary capacity-building activities: It is highly recommended that future digital interventions aiming to achieve similar results carry out preliminary capacity-building activities, such as a dedicated introductory phase for digital training. This will ensure that teams and PMUs are equipped with the necessary skills and knowledge to effectively implement digital solutions, efficiently adapt ICT4D tools to the local context, and maximize their ability to sustainably impact development outcomes.

- Implement M&E frameworks during the design phase: In order to accurately assess the effectiveness and impact of digital initiatives, it is paramount that clear M&E methodologies – as well as a structured approach to introducing these frameworks – be included in the program’s design. Doing so enables teams to easily track progress, effectively maintain alignment with the program’s objectives, and efficiently evaluate how well the digital components were implemented, as well as their ongoing impact on driving systemic change.

- Provide long-term ICT4D support: Finally, it is important to note that short-term advisory missions often lack the depth needed to fully implement programs that provide technical assistance. As such, it is recommended that long-term technical assistance be provided within IFAD’s projects to foster continuity, mentorship, and problem-solving beyond initial design, ensuring impact continues to evolve well after the program’s close.

Democratizing Digital or Digitizing Democracy in 2025?

In 2023, I wrote about the OGP Global Summit in Tallinn, Estonia, and its focus on digital democracy. Estonia put digital democracy on center stage, showcasing e-Estonia and the digitization of government services such as legislation, voting, education, justice, healthcare, banking, taxes, policing, etc. e-Estonia is an example of digitizing democracy.

Also prevalent at the 2023 Summit was the concept of democratizing digital, or ensuring that digital tools, platforms, and policies are made and governed in ways that reflect democratic values. Open government and digital democracy can improve transparency, accountability, and participation in society. However, open government mechanisms and digital democracy must be usable, accessible, and inclusive.

Former Estonian Prime Minister Kaja Kallas delivers her keynote at the 2023 OGP Summit (Image: OGP)

As we approach the 2025 OGP Summit, the Government of Spain and Cielo Magno have prioritized the themes of People, Institutions, and Technology & Data. These themes signal that democratizing digital and digitizing democracy remain cornerstones for building resilient, effective, and trusted institutions.