Diving into the DaYTA Program’s Data Collection Process

Development Gateway: An IREX Venture’s DaYTA program seeks to advance tobacco control efforts by gathering data on tobacco use among 10- to 17-year-olds in Kenya, Nigeria, and the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC). The findings from the DaYTA program will be eventually integrated into the existing country dashboards on the Tobacco Control Data Initiative portal, which can be found at https://tobaccocontroldata.org/en. Having this timely and representative data will ultimately enable policymakers to formulate targeted, data-informed interventions to prevent and/or address the initiation of tobacco use among youth.

This blog will explore key insights from the program, offering practical guidance for researchers on effective data collection, overcoming field challenges, and leveraging local partnerships to enhance tobacco control efforts. This piece is in accompaniment to DaYTA’s workshop convening all 3 study country stakeholders to review the survey results and strategize on how best to disseminate this data to target audiences, in Lagos, Nigeria, from November 18-20th.

Overview of DaYTA’s Data Collection Process

A core milestone of the DaYTA program was primary data collection. Between April and June 2024, data collection was carried out in all three countries of implementation. Using data from the co-design workshop in Naivasha, Kenya, in late October 2023, a central study management and coordination team identified priority topics applicable to all three countries and those tailored to each country’s unique needs. The priority topics identified, constituting the “core” modules to be featured on the respective DaYTA website pages, include:

Challenges Faced & Solutions Deployed

The DaYTA survey’s methodology was more inclusive because it was household-based versus school-based. However, this presented its own challenges–ranging from absent heads of household, parental interference, access issues to wealthy urban areas, and rugged terrain in some enumeration areas (EAs). Field researchers advanced several practical, context-specific solutions to overcome these challenges, laid out below:

Navigating Parental Concerns: As this was primarily fueled by mistrust, field researchers clarified the research objective and purpose with both heads of household and youth participants. In DRC, these discussions helped gain parental approval when enumerators faced resistance in the Sud-Kivu province. Across countries, the use of slang was used to break the ice with youth participants. This worked quite well, as field researchers were relatively young. In some instances, parents insisted on being present during interviews. This was not permitted as the presence of a parent can influence the honesty and openness of the youth’s responses.

In some cases–particularly in the DRC–parents actually encouraged field researchers to speak with their children due to the beneficial educational information. The DG team celebrated this anecdote as there was a lingering concern that communities might perceive field researchers as “outsiders” attempting to “corrupt” their kids, but in reality, parents considered field researchers the source of truth. In Kenya, youth participants felt respected by virtue of being asked for their consent to be interviewed rather than just their parents.

Flexible and Strategic Planning for Door-to-Door Data Collection:: Generally speaking, this approach demanded meticulous scheduling and multiple visits due to out-of-control variables such as school schedules, absence of heads of household, access restrictions to certain areas, and others. In DRC, some provinces were relatively straightforward (i.e., Tshuapa and Kasai), given that households were closely grouped or household schedules proved favorable.

However, DRC field researchers also noted that conducting interviews in rural areas required significant effort, as the heads of household were often absent, necessitating multiple visits throughout the day. In rural areas of Kenya, field researchers adapted to constraints posed by traditional gender norms, dictating that a man cannot interview an adolescent girl. To address the concerns about the gender dynamic, female field researchers interviewed adolescent girls or teamed up with one male and one female enumerator visiting an enumeration area (EA) together.

In Kenya and the DRC, field researchers encountered issues accessing households in wealthier urban neighborhoods that were gated communities. To mitigate this, the Kenya data collection firm tried to obtain permits from residential associations to gain access. However, this was unsuccessful. Instead, those areas were omitted and the enumerators moved to other EAs.

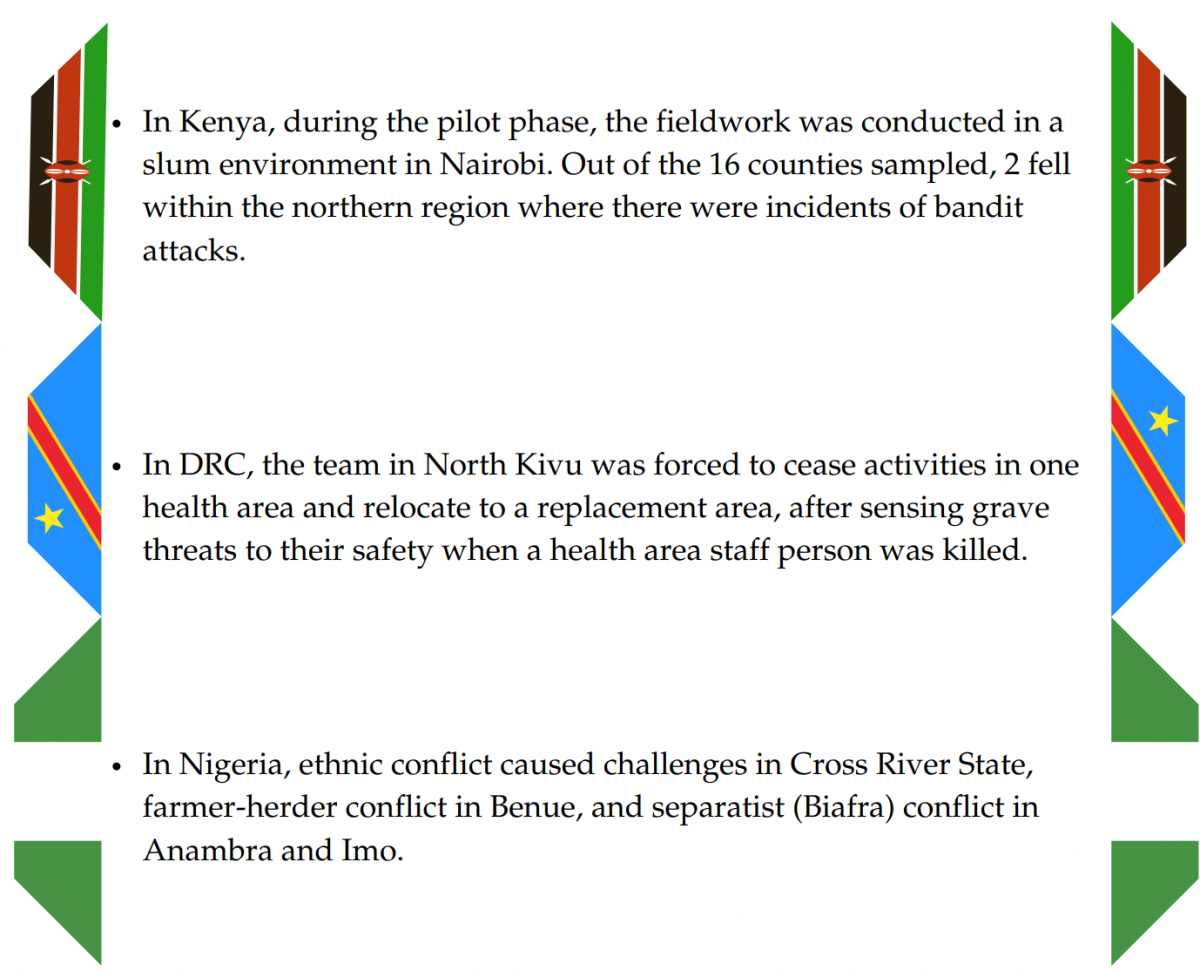

While the root of the security concern differs by country, all three DaYTA countries experienced some form of security issue—from localized to widespread:

The following country-specific provisions were made to ensure the team’s safety:

- In Kenya, a security detail was provided for field researchers in Nairobi slums during pre-testing;

- In the DRC, staff members were quickly evacuated from areas of concern; and

- In Nigeria, field activities were postponed until after Biafra day.

Standardizing best practices while tailoring to the local context: Field researchers operated in diverse settings necessitating variable modes of communication, approaches, etc., impacted by the prevailing sociocultural context. In Kenya, field researchers were required to speak the two national languages–Swahili and English–but if the head of household didn’t speak either, they would switch to the local language. Proper planning ensured that field researchers sent to specific areas came from that particular tribe. This also added the benefit of building rapport and trust with the youth and parents.

The DaYTA Comparative Advantage

The DaYTA research distinguishes itself from other global youth tobacco surveys in a multitude of critical ways:

- It was nationally representative: During DaYTA’s rapid assessment conducted in the fall of 2023, one stakeholder explained that the lack of nationally representative data required them to review data collected in neighboring countries to better understand the trends throughout regions outside of the major urban areas. Due to the vast size of the DRC and its history of security challenges, DG initially planned to survey select provinces. Fortunately, we selected a data collection firm with extensive experience implementing research in rural DRC and delivered a nationally representative survey, with a record 16 provinces being completed.

In Kenya, DG partnered with the Kenya Bureau of National Statistics (KNBS), and in Nigeria, DG partnered with the National Population Commission (NPC). These partners’ expertise and official data on enumeration areas provided a scientifically and nationally recognized sampling frame that will assist with the validity and credibility of DG’s findings. Further, the partners’ access to accurate and up-to-date data helped facilitate the government’s buy-in and ownership of the DaYTA research. In Nigeria, when security issues arose in specific data collection areas, the NPC’s proactive response was a testament to its commitment to the success of the DaYTA project. It quickly re-randomized and provided new enumeration areas. This flexibility helped maintain the integrity and continuity of DG’s survey, allowing the team to avoid delays and ensure the safety of field teams.

- The high level of compatibility between DG and the local partners made all the difference: This demonstrated DG’s commitment to leveraging the power of local human resources and respecting national institutions by subcontracting to country-based firms and having them recruit locally. This proved vital for fostering trust and collaboration with government stakeholders. It serves as a crucial reminder to think carefully when selecting your research partners and consider if they are present (in some capacity) in a wide range of geographic areas.

- The sampled age group was comprehensive: Many global youth tobacco surveys are limited to in-school youth and cover a narrower age range. With this in mind, we sampled 10-17-year-olds and decided to go with a household-based survey to ensure that both in-school and out-of-school adolescents were reached, whether emancipated or not. Targeting this demographic was especially critical in light of recent data from the UNESCO Institute of Statistics indicating that nearly 60% of youth between the ages of 15-17 are out-of-school.

- It covered the use of new and emerging products: Due to the outdated nature of the most recent Global Youth Tobacco Survey (GYTS) reports in each DaYTA country, emerging products were not included, except in Kenya. These products are gaining popularity worldwide, especially among youth and adolescents. Evidence shows a strong association between the use of these products and being an ever-smoker or having recently smoked combustible cigarettes. However, data on these products is only routinely collected in some countries; it is optional for countries to collect this data in the GYTS.

Looking Ahead…

DaYTA’s workshop is convening stakeholders from all three program countries, spanning members of academia, civil society organizations, and government. On top of gaining a more in-depth understanding of the survey results, the meeting also aims to support stakeholders in:

- Formulating creative and interdisciplinary strategies for engaging youth in tobacco control advocacy,

- Considering challenges and mitigation measures gleaned from DaYTA’s research design and methods for due consideration in potential future studies, and

- mapping work plans and key performance indicators for Year 3 of the program.

Demystifying interoperability: Key takeaways from our new white paper

Government offices are filled with siloed, sector-specific digital systems that strain their capacity to make decisions, use data effectively, and achieve ambitious sustainable development goals. Public investments in digital development, transformation, and infrastructure can only meet citizen needs if data and systems are consolidated and interoperable.

While interoperability is a sensible approach to building digital public infrastructure, transforming existing systems is easier said than done. Limited resources and expertise, lack of training, inadequate hardware and software infrastructure, and concerns over data privacy are some of the key factors that limit the impact of systems or lead to their discontinuation. The data that feeds these systems also needs to be standardized using global best practices and common languages and frameworks that can be understood across multiple platforms and adapted to the local context. In increasingly digital economies, systems and their data need to be relevant and responsive to citizens’ specific conditions and needs With emerging challenges like climate change that require more complex data, and new technologies like artificial intelligence (AI) that require large volumes of data, systems need to be agile and scalable to advance solutions and fully harness innovation.

Our latest paper discusses, in practical terms, what goes into implementing interoperable solutions in partnership with public administrations. Based on over 20 years of DG’s experience, the paper demystifies key components needed to build robust, resilient, and interoperable data systems, focusing on the “how” of data standardization, data governance, and implementing technical infrastructure.

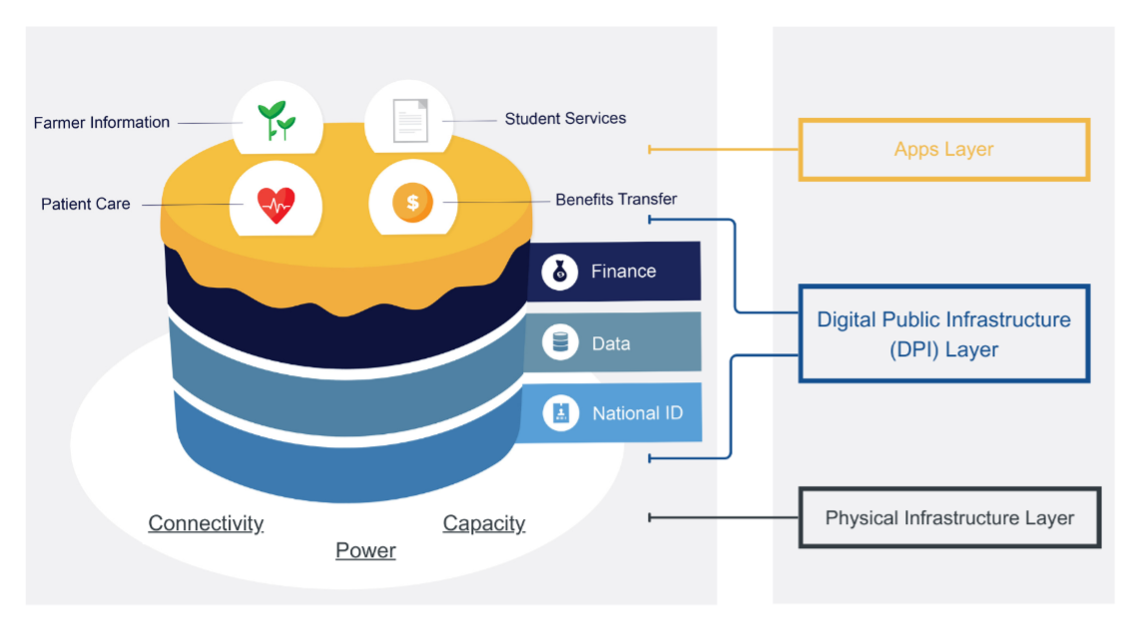

Image from Demystifying interoperability, 2024

Setting up Data Standards

Data must be standardized for consistent and seamless exchange between different systems. Without standardization, systems cannot “talk” to one another, limiting users’ ability to gain deeper insights from combined data sources. Standardization can be a long process as not all data can be acted upon at once; certain datasets and systems need to be prioritized with a view to scale over time. Moreover, data standards are about the people who use them: it takes time for the people who know their data best to change data collection and usage methods over time. Inclusive data standards processes draw diverse stakeholders together for a win-win scenario: everybody can make better decisions that drive productivity when they can see the same picture together.

Cultivating Adaptable Data Governance

Many countries do not have a clear “whole-of-government” policy on data sharing and access. This absence matters for interoperability because systems will struggle to remain usable without a consistent flow of quality data that can be shared. To tackle this challenge, Chapter 3 looks at the practical and legal frameworks that govern how key digital systems in the Ethiopian Ministry of Agriculture manage and control data availability, usability, integrity/quality, and security. Incorporating a data governance lens into the technical development of systems increases data accuracy and consistency by taking the guesswork out of data sharing.

Building Up the Technology

What counts as “good” digital public infrastructure is hard to define, especially when there are several well-known problems. For example, there are systems that cannot be modified without re-engaging vendor support; platforms with rapidly outdated technology; and difficult-to-manage storage solutions that lead to data loss. Smart development of digital infrastructure boosts efficiency and builds trust, making services more responsive to citizen needs. Solving these challenges requires a holistic approach that addresses software, hardware, and local IT infrastructure and capacity.

Recommendations

One program cannot address all problems! The following recommendations reflect the systemic shifts required to build better technology across sectors as well as the forward-looking opportunities that set up public technology for the future.

- View digital transformation on a maturity axis, rather than a transition from point A to B.

- Understand what already exists to set priorities.

- Use what exists to define the scope.

- Institutionalize sustainability from the outset in every dimension: human, institutional, technical, and financial.

- Take a portfolio view of digital transformation that puts interoperability at the center. Country digital roadmaps can guide priorities across multiple digital needs.

- Recognize that transformation requires champions.

- Ensure data standards stretch across sectors and regions.

- Keep watching and actively collaborating with telecommunications outfits as the numbers of local cloud providers continue to grow.

- Invest in national legal frameworks for responsible data sharing.

- Do not forget the people.

Shared Struggles, Shared Solutions: Education and Cross-Sector Data Use Insights

This blog draws on DG’s experience in climate, health, aid management, and agriculture to explore connections between the challenges of data collection, data hosting, and data governance across different sectors and what the solutions to overcoming them can teach us about strengthening education data systems.

Economic Toll of Tobacco-Related Diseases in Kenya: New Research Findings

Development Gateway: An IREX Venture (DG) is pleased to announce the publication of a research manuscript on the Economic Costs of Tobacco-Related Illnesses in Kenya. This research was carried out as part of the Tobacco Control Data Initiative (TCDI) activities in Kenya and is part of a broader report on Morbidity and Mortality from Tobacco Use in Kenya.

The Data Crisis Following USAID’s Withdrawal: Opportunities to Reimagine Data Systems

For decades, USAID and other US government funding supported global data systems, from health surveys and early warning tools to digital infrastructure for ministries. The abrupt termination of USAID funding has triggered twin crises: a halt to data collection and the undermining of digital systems – reveal existing inefficiencies and instabilities in how data is collected, managed, and shared both within and between countries.

More Smoke, More Stroke

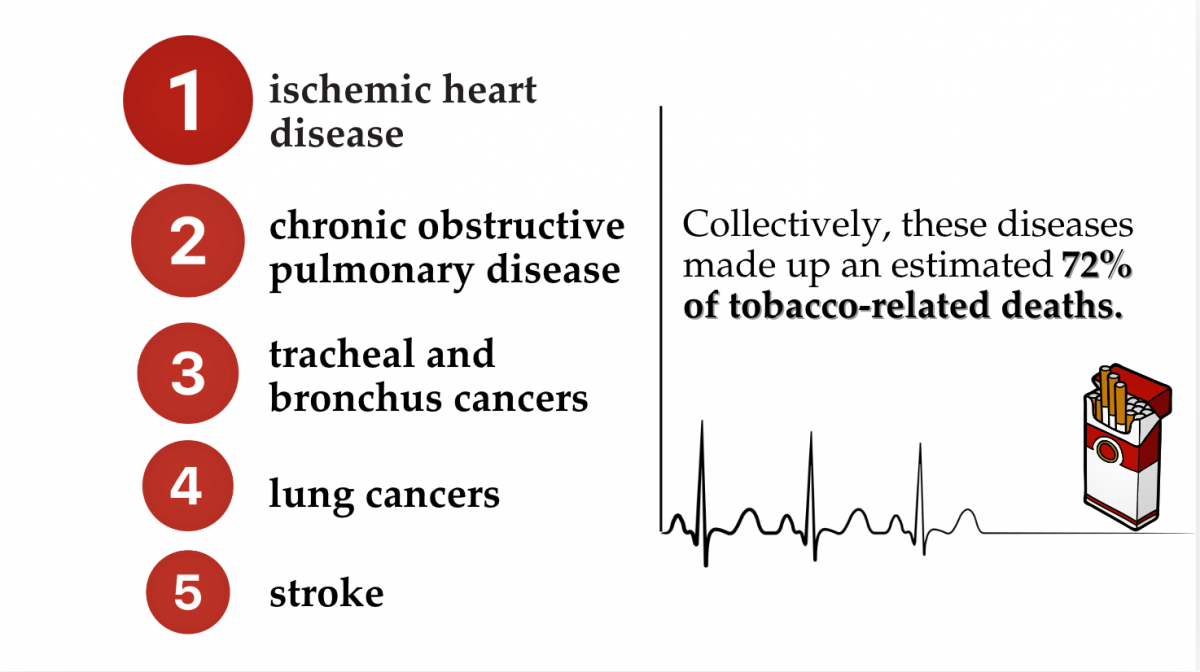

According to a 2021 report by The Lancet, stroke was the third leading cause of death worldwide, after ischemic heart disease and COVID-19, based on the Global Burden of Disease (GBD) classification. The data further shows that stroke accounts for an estimated 12 million cases and over 7 million deaths globally each year.

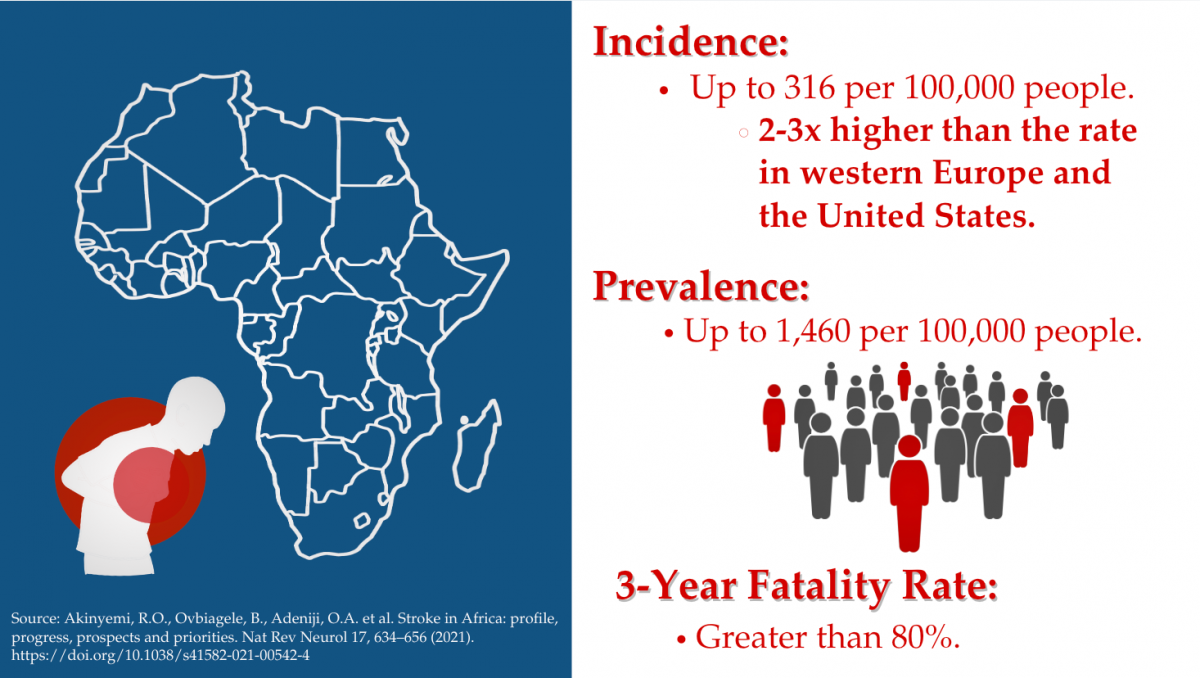

Africa is home to some of the highest rates of stroke worldwide, with alarming incidence, prevalence, and fatality rates. Recent figures detailed in the infographic below underscore the importance of pragmatic and concerted public health interventions.

Considerable scientific evidence has found that cigarette smoking is a causal risk factor for all forms of stroke. This is due to the inflammation wreaked on blood vessels, leading to the formation of clots, buildup of plaque in the arteries, or general weakening of the blood vessels.

The two main types of stroke include ischemic and hemorrhagic. Ischemic strokes are the most prevalent and refer to when a blood clot has blocked blood vessels in the brain. Given that smoking causes the blood vessels to narrow–triggering plaque and clots–this increases the risk of an ischemic stroke. Hemorrhagic strokes–or bleeding strokes–occur when a blood vessel (specifically, an artery) in the brain ruptures, causing blood loss and damage to the brain. The nicotine and carbon monoxide found in cigarette smoke weaken the arteries, which makes them more susceptible to bursting or breaking, leading to a hemorrhagic stroke.

To put it into perspective, up to one-quarter of all strokes are directly attributable to smoking. Smokers are twice as likely to suffer from a stroke event, and twice as likely to die from them. This risk increases with frequency–smoking 25 or more cigarettes daily (e.g. exceeding one pack of cigarettes) leaves users five times more likely to suffer from a stroke event, and about five times more likely to die from one.

Given these alarming statistics, raising awareness is crucial. In honor of this year’s World Stroke Day, observed annually on October 29th, this piece aims to raise awareness of the substantial burden of non-communicable diseases–particularly stroke incidents–using the case study of Nigeria, one of the main tobacco production hubs on the continent, in addition to Kenya.

Awareness of links between cigarette smoking and strokes still needs to improve in many parts of the world, including Africa. Supporting better tobacco control policy design and implementation in Africa, the Tobacco Control Data Initiative (TCDI) seeks to improve access to country-specific tobacco control data for governments, civil society, and academia. The six country-specific TCDI websites provide stakeholders with data to inform the design and implementation of effective tobacco control policies through comprehensive primary and secondary research.

The Link Between Secondhand Smoke and Stroke

Unfortunately, no level of exposure to secondhand smoke is risk-free. Scientific evidence has shown that secondhand smoke is a causal risk factor for strokes. Breathing secondhand smoke increases the risk of stroke by 20 to 30 percent. There is even another layer of exposure–known as thirdhand–which refers to the lingering residue from tobacco smoke that can be detected on surfaces, furniture, floors, curtains, and walls for several months. These enclosed spaces absorb the tobacco smoke toxins and gradually

release them back into the air. Infants and young children are thought to be the most susceptible to this type of exposure, likely due to development behaviors (e.g. having a breathing zone closer to the ground) that lead them to reportedly ingest double the amount of dust particles compared to adults.

In this piece, we’ll discuss the stroke-related implications of tobacco usage with an emphasis on the health and economic burden in Nigeria. The following sections feature data presented in a 2019 modeling study conducted by the Centre for the Study of Economies in Africa, Development Gateway’s sustainability partner on TCDI, in addition to a recently published research manuscript on Mortality from Tobacco Use in Kenya, carried out as part of TCDI’s activities in Kenya. Data from this research may also be found on the TCDI Kenya dashboard.

Health and Economic Costs of Smoking Tobacco in Nigeria

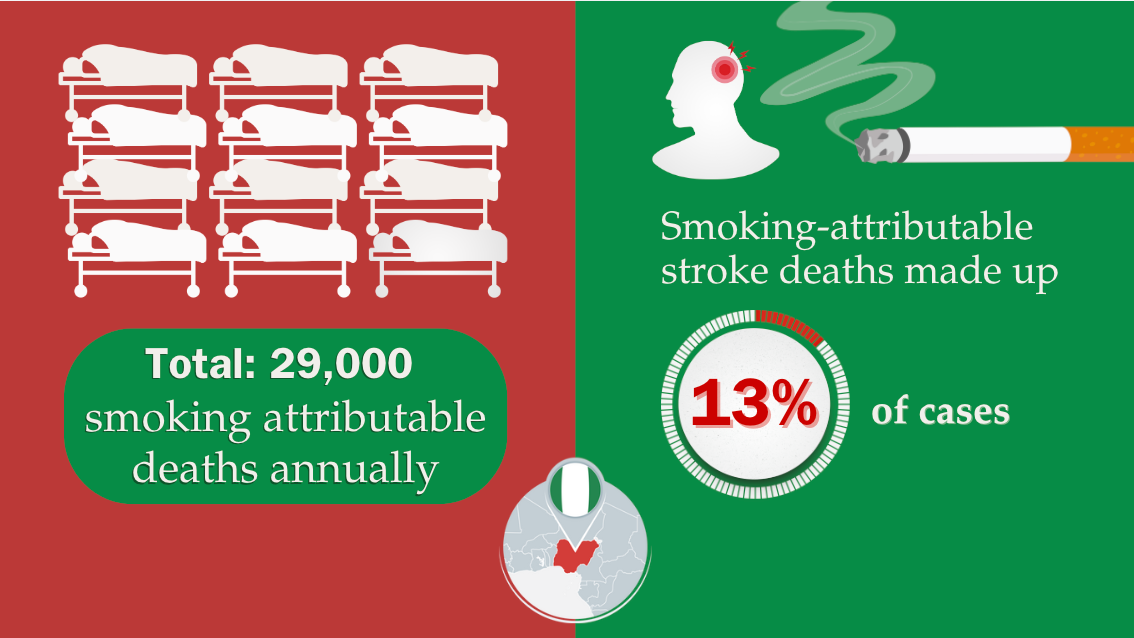

Nigeria reports the highest absolute number of active smokers on the continent. Smoking is responsible for approximately 29,000 deaths per year. Tobacco-attributable stroke events represented 13 percent of cases, after Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease (63 percent).

In 2019, the total economic burden of tobacco in Nigeria was estimated at 634 billion Naira, or approximately USD 2.07 billion. This includes direct and indirect medical treatment costs (i.e., productivity losses and informal caregiving). CSEA’s 2019 modeling study in Nigeria studied four hospitals over three Nigerian regions, namely Oyo (Southwest), Enugu (Southeast), and Abuja (North). Direct medical costs for stroke were micro-costed at 1.2 million Naira, or approximately USD 730. Indirect costs were micro-costed at 363 thousand Naira, or USD 220.

The TCDI Kenya team published a research manuscript quantifying the mortality burden attributable to smoking tobacco in Kenya, from 2012 to 2021. Over the 9-period studied, 60,228 deaths were attributed to tobacco-related diseases. Approximately 9,948 (16.5%) of these observed deaths were attributed to smoking, with cardiovascular diseases–including stroke–accounting for an estimated 885 deaths (8.9% of the total).

Strengthening Tobacco Control Through Tax Reform

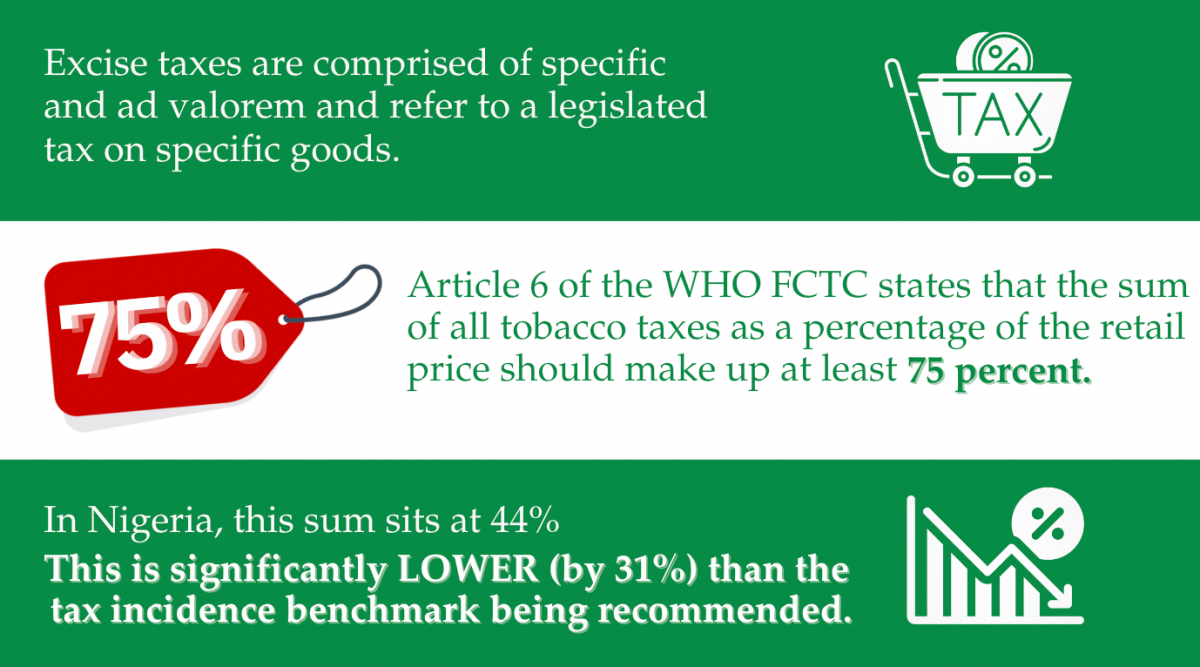

The following bullet points highlight two effective tobacco control policy interventions described in CSEA’s 2018 study titled “The Economics of Tobacco Control in Nigeria: Modeling the Fiscal and Health Effects of a Tobacco Excise Tax Change in Nigeria.” The study recommended that such interventions should comprise of the following:

- Changing the tax system from ad valorem to specific excise taxes.

Ad valorem taxes are based on the value of the products (e.g., a percentage on the factory or retail price), while specific taxes are levied based on quantity (e.g., tax per carton/per cigarette/per gram loose-leaf). A specific excise tax system is recommended because it leads to higher retail prices–offering a more predictable revenue stream–and is easier to administer than ad valorem taxes. Additionally, specific excise taxes treat all tobacco products equally, meaning that tobacco products pay the same amount of tax, regardless of brand or product type. So, in short, a simpler tax system is favorable.

- Continuously increasing the excise tax burden on tobacco products.

Excise taxes are comprised of specific and ad valorem and refer to a legislated tax on specific goods.

Ultimately, increasing the tax burden on tobacco products would save lives. If the price of cigarette packs were to increase by 50 percent through taxes, in a decade, 30,000 smoking-attributable deaths would be prevented, and 21,000 strokes would be avoided. Savings from direct and indirect costs equate to 597 billion Naira, and additional earned tax revenue amounts to 369 billion Naira.

A prime avenue for promoting public health and fostering sustainable development is embedding comprehensive tobacco taxes in a country’s tobacco control strategy. This tax-based approach is especially advantageous in light of the significant–and sometimes prohibitive–costs of funding tobacco control interventions. It represents a win-win measure, as countries can benefit from the additional earned tax revenue while focusing on competing national priorities. This strategy should also feature recommended policy measures detailed in the FCTC, such as graphic health warnings, bans on tobacco advertising, promotion and sponsorship, and smoke-free areas.

World Stroke Day is key in promoting awareness of stroke prevention, early recognition of symptoms, and the critical role of lifestyle choices in reducing risk. This global day brings attention to the preventable nature of strokes and encourages worldwide efforts to support healthier lifestyles, including smoking cessation, to reduce stroke incidents.

New Research Manuscript on Mortality from Tobacco Use in Kenya

Development Gateway: An IREX Venture (DG) is pleased to announce the publication of a research manuscript on Mortality from Tobacco Use in Kenya. This research was carried out as part of the Tobacco Control Data Initiative (TCDI) activities in Kenya and is part of a broader report on Morbidity and Mortality from Tobacco Use in Kenya and the Economic Costs. Data from this research is available on the TCDI Kenya dashboard, which aims to supply decision-makers in government, members of civil society, and academia with improved access to country-specific data to better inform tobacco control policy.

This is the second of three manuscripts which seek to break down the research report’s findings. The first, published in November 2023, explored the prevalence, patterns, and factors associated with tobacco use among patients with tobacco-related illnesses such as cancers, cardiovascular disease, chronic respiratory disease and diabetes.

This blog highlights some key findings in the manuscript from the research carried out in Kenya in 2021 on morbidity and mortality from tobacco use in Kenya and the economic costs thereof.

Why research on Mortality from Tobacco Use in Kenya?

In Kenya, about 12,000 individuals die from tobacco smoking each year. Tobacco smoking is a risk factor for numerous diseases, including chronic respiratory diseases, cardiovascular diseases, various cancers, and diabetes. Tobacco use results in disability and death and imposes significant economic costs on Kenya’s health system and economy. In 2020, Kenyan tobacco control stakeholders requested domestically collected and analyzed data on mortality arising from tobacco use in Kenya to assist decision-makers make and implement tobacco control policies.

Key findings from the research

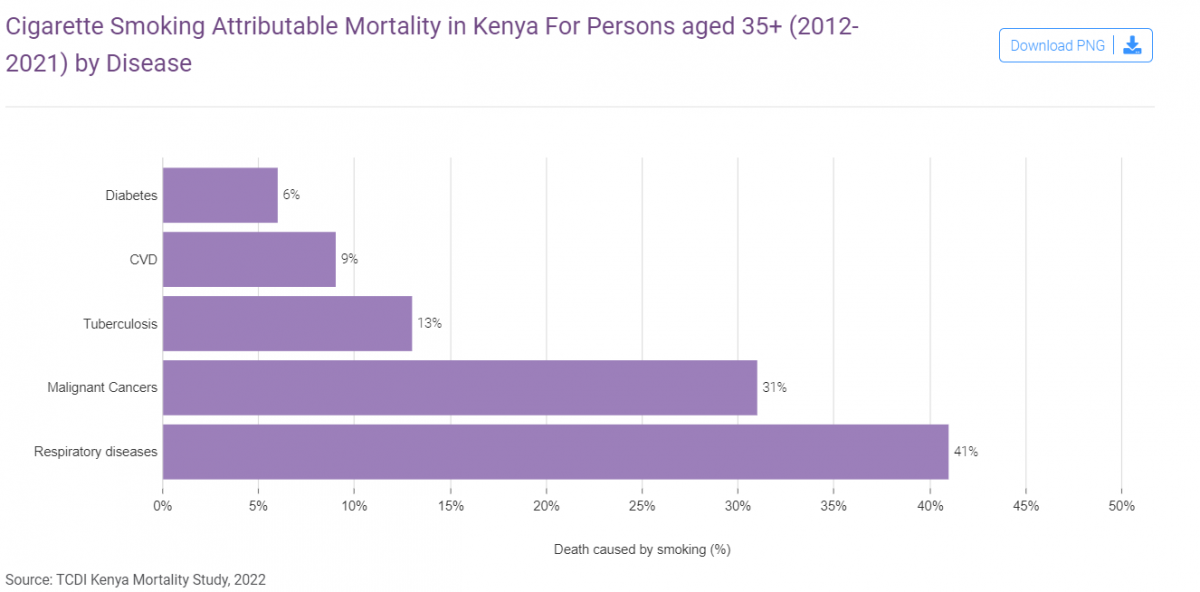

All-cause mortality data of deaths that occurred in Kenyan health facilities at sub-county, county and national levels between 2012 and 2021 was systematically reviewed from hospital medical records. Deaths arising among persons 35 years and older from five types of tobacco-related illnesses (respiratory diseases, diabetes mellitus, malignant cancers, tuberculosis, and cardiovascular diseases) were identified, and the fraction of deaths attributable to tobacco smoking was calculated.

Between 2012 and 2021, Kenya experienced 60,228 deaths attributed to tobacco-related diseases (respiratory diseases, diabetes mellitus, malignant cancers, tuberculosis, and cardiovascular diseases) among adults aged 35 years and older. The age of 35 years is significant as these are classified as premature deaths that occur when people are still economically productive.

Out of the 60,228 observed deaths, 9,943 (16.5%) were attributed to tobacco smoking.

Out of the 9,943 deaths attributable to tobacco smoking, 8.7% were women, and 91.3% were men, primarily because men smoke more than women. The major contributors to mortality included respiratory diseases (41%), malignant cancers (31%), tuberculosis (13%), cardiovascular diseases (9%) and diabetes mellitus (6%).

Among respiratory infections, pneumonia and influenza (86%) predominated, surpassing COPD (13%) and bronchitis/emphysema (1%). The year 2020 witnessed a significant twofold increase in pneumonia and influenza deaths, attributed to COVID-19.

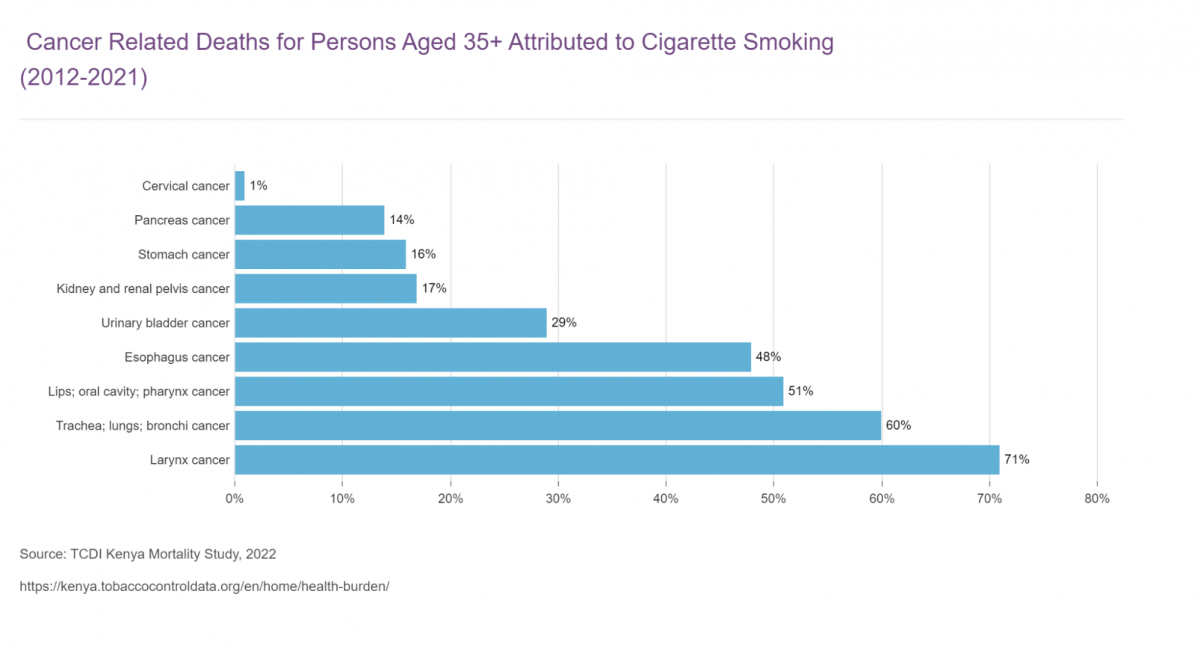

Noteworthy cancers with the highest deaths included larynx cancer (71%), lung cancer (60 and oropharyngeal cancer (51%). Cerebrovascular diseases (87%) emerged as the primary cardiovascular cause of death, followed by ischemic heart diseases (10%) and other arterial diseases (3%).

To address the significant impact of tobacco-related diseases on mortality in Kenya, a multifaceted approach to intervention is needed, including:

- Progressively and regularly increasing tobacco taxes and enforcing smoke-free policies in public spaces to reduce tobacco consumption and exposure to secondhand tobacco smoke.

- Comprehensive public awareness campaigns, utilizing various media channels to emphasize the association between tobacco use and diseases highlighted in the study findings.

- School-based programs to educate the younger population about the dangers of tobacco, aiming to deter initiation.

- Training of healthcare providers to offer effective smoking cessation counseling during routine visits, and access to cessation resources should be improved.

The final manuscript from the research report will focus on the economic burden of treating tobacco-related illnesses, to be published in the coming months. If you would like to learn more about TCDI and explore country-specific data, kindly visit www.tobaccocontroldata.org.

Mythbusters: Digital Public Infrastructure & Digital Public Goods

This blog is the third in our series exploring digital public infrastructure. From DG’s more than 20 years of experience in creating, delivering, and adapting open source and open data solutions, we’ve learned several best practices on how to make technology accessible and sustainable while prioritizing engagement from open source communities—these practices can be applied to building and implementing digital public infrastructure. Check out the other blogs in this series.

Since India popularized the term during it’s G20 presidency, digital public infrastructure (DPI) is the latest buzzword in ICT4D that everyone from Deloitte to UNDP to Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation is talking about. But the concept itself is not new: the internet and GPS are some of the earliest examples of DPI, and DG has a long history of building and advising on technology to support government service delivery. Although the international community has just now reached consensus on what digital public infrastructure is, there are still a lot of myths and misperceptions around the term, and the open-source technology that often powers it. In this blog, we’ll debunk some common myths we hear about DPI with facts, highlight some successes and failures, and show you some of the open-source DPI tools we’re following.

MYTH #1: Governments shouldn’t get in the business of building technology; leave digital infrastructure to the private sector

From distributing life-saving shelter, food, and medical attention after a disaster; to delivering government subsidies for seeds and fertilizer to smallholder farmers; to enrolling students for national examinations— these are the kinds of “public goods” not unlike roads that require a non-invisible hand to ensure citizens have equal and fair access. At a foundational “building block” level, this includes digital systems that give citizens:

- The ability to verify their identity

- The ability to share data accurately and securely

- The ability to make and receive payments

Source: Digital Impact Alliance.

Look no further than the US Department of Education’s disastrous handover of its loan repayment servicing to private-sector debt collectors like Mohela to understand the impact on student borrowers, let alone the Department of Education’s ability to collect payments. Or consider that the average American spends 13 hours and $240 on third-party tax software each year just to file taxes; and despite it being ostensibly free, standardized, and compulsory, 33% of Americans “completely” or “mostly” disagree that they trust the IRS to help them understand their tax obligations. In sum, the consequences of a free market approach to government digital transformation are felt most severely by citizens, which can foster and in some cases exacerbate mistrust in government technology systems.

MYTH 2: DPI, and the APIs and open-source software used to power it, are less secure and of lower quality because they’re free.

You’ve probably been using some very high-quality open-source technologies yourself and just didn’t know it. Some of the most widely-used examples of open-source software, both inside and outside of government, include the Linux operating system, Apache web server, and PostgreSQL database. Open-source tools specifically for DPI, also known as digital public goods, include DHIS2 for health; Moodle for education; openCRVS for civil, birth, and death registrations; the Open Contracting Platform for government procurement; and OpenStreetMap for GPS and mapping data.

The demand for these tools speaks to their quality: DHIS2 alone has been adopted in over 74 national health systems, and will be adapting its model for the education and agriculture sectors. And even if one of the existing open-source DPI tools doesn’t meet your exact quality standards, the beauty of open source is that you can customize or build on top of the foundational infrastructure to build any solution you want, much like we did for local health districts in Tanzania and the Ministry of Agriculture in Ethiopia.

Source: AfrICT (Africa ICT)

Piecemeal approaches to digital systems can make governments more vulnerable to potential risks. While open-source technology does have vulnerabilities (like any software), using open-source for DPI is arguably more secure than the alternative because it allows for cross-system interoperability, data validation, and cross-referencing. Public code review forums like GitLab (also open-source) and GitHub give users access to the latest security upgrades, bug fixing, and risk mitigation measures that would otherwise require extensive long-term support contracts or subscriptions. India regularly invites the best hackers in the country to intentionally break into the open APIs that power its digital public infrastructure, India Stack, and these hackathons have enhanced the security and protection of the technology.

While OSS can reduce licensing costs, there are still costs associated with implementation, customization, maintenance, and training. DPI projects also require substantial investments in infrastructure, development, and ongoing support. Taipei, for example, recently invested US$6.27 million to roll out a digital national ID program but had to pause in 2021 due to security concerns. Other experts in India estimate that the average cost of a digital identity program is about US$1 per person; meanwhile, costs for digital payment infrastructure can range from US$100 million in Thailand to only about US$2 million in Brazil.

However, the long-term economic impacts for society greatly outweigh the costs of deploying DPI. A McKinsey study recently estimated that Digital ID alone can boost economies by 3–13% of GDP, with an average of 6% growth in emerging economies. Governments that opt for open-source DPI can benefit from additional long-term cost savings by not having to renew licenses or software agreements, and adjusting or maintaining the technology in-house rather than contracting a third party.

MYTH 3: DPI increases inequalities and expands the digital divide

A recent Deloitte study confirmed that DPI can strengthen the government’s digital systems and facilitate equitable access to digital services. Take for example the successes of Ghana Post GPS, a digital addressing system that provides every location in Ghana with a unique digital address. Aside from ensuring your maps app will navigate you to the correct destination in Ghana (“Eye” Street in DC, I’m looking at you), this tool has improved citizens’ ability to access services, including emergency response, mail, and e-commerce; enabled more inclusive access to services for residents in remote and informal settlements; and facilitated business operations and logistics by providing precise location data.

DPI, when implemented with open data principles, can increase government transparency and accountability, enabling citizens to access and analyze public information. If implemented responsibly, DPI makes anonymized and real-time data available to citizens and civil society watchdogs, and the transparency provided by DPI can help improve civic engagement, increase trust in government, and credibility in a country’s decision-making. Further, by allowing anyone to contribute, open-source technologies foster innovation and collaboration across different sectors and geographies. Digital Public Goods communities have global reach and active online communities, which further support the reputation, neutrality, comparability, and trustworthiness of these systems.

In addition, open-source DPI solutions allow governments to avoid being locked into a single vendor’s ecosystem. This gives governments more flexibility and control over their IT systems, preventing dependence on high-cost, long-term contracts with the private sector. By using and developing their own digital infrastructure, governments can reduce dependency on foreign technology providers and protect their data sovereignty.

Looking ahead

Digital transformation offers countries the chance to establish robust public infrastructure and learn from others’ mistakes. However, challenges arise due to the lack of clear legal, regulatory, and policy frameworks for establishing interoperability across different ministries with distinct budgets, IT capabilities, capacities, and needs. Implementing digital public infrastructure also means answering questions related to governance, ownership, collaboration, resource-sharing, and sustainability. For instance, questions about who funds and maintains APIs between systems or how to integrate different platforms for various purposes highlight the complexities involved.

One solution could be establishing an independent intergovernmental agency, much like the UK’s Government Digital Services, to oversee and coordinate digital infrastructure. In emerging economies, development institutions and international banks can play a crucial role in financing public infrastructure, but purchasing the technology is not enough: DPI and DPG adoption must be supported by a robust and ethically governed regulatory environment to be sustainable. At DG, we look forward to continuing to work with our country government partners on their digital transformation journeys to dispel myths and misconceptions about DPI and DPGs, scale benefits to citizens by optimizing interoperability across sectors, and develop strong governance and accountability mechanisms that safeguard citizen and community rights.

Healthy Farming, Healthy Planet: The Environmental Case Against Tobacco Farming

DG’s Tobacco Control Data Initiative (TCDI) aims to improve access to country-specific tobacco control data for governments, civil society, and academia, supporting better tobacco control policy design and implementation. The six country-specific TCDI websites present data and information on tobacco control through rigorous primary and secondary research. We’ve spoken at length about the health burden and harm caused by tobacco use, but did you know that tobacco farming is deeply harmful to the environment as well? While all agriculture has an environmental impact, tobacco is unique in that every stage of the tobacco lifecycle–from the production and consumption of tobacco to farming and disposal of the final product–wreaks havoc on the environment.

In this piece, we’ll introduce the lifecycle of producing and using tobacco and explore the requisite environmental impact:

1. Cultivation:

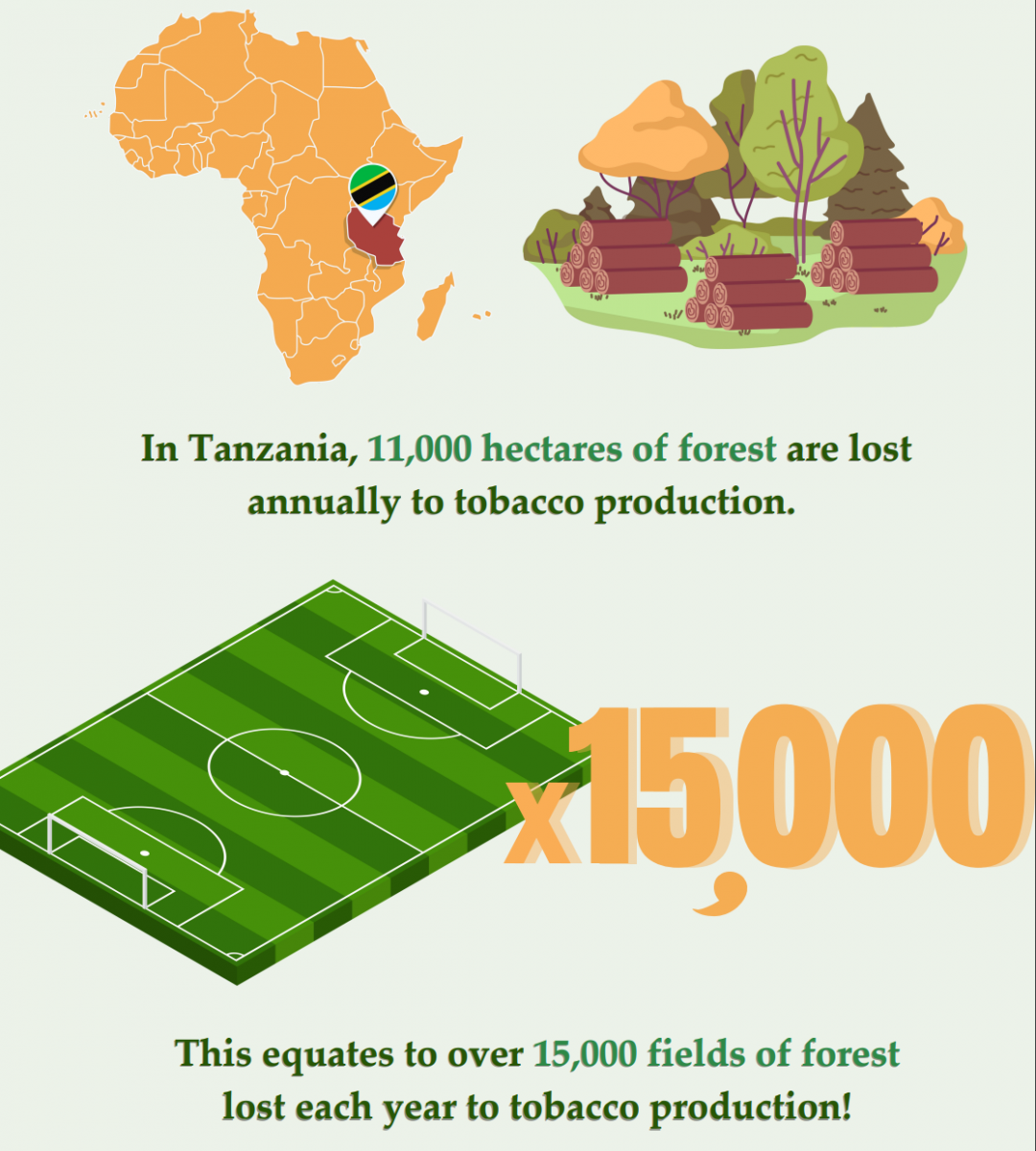

The first stage of the process is cultivation, or growing tobacco. Tobacco farming is a direct cause of deforestation, as farmers have to clear woodland reserves to prepare the land for tobacco cultivation. Tobacco-related deforestation accounts for up to half of the total annual loss of forests and woodlands. Additionally, early 90 percent of tobacco agriculture in Africa occurs in the Miombo ecosystem, the world’s largest contiguous area of tropical dry forests encompassing Tanzania, Malawi, and Zimbabwe.

Source: Land Degradation and Development Journal, Volume 28, Issue 8

Deforestation has wide-reaching effects, threatening plant and animal diversity and whole ecosystems, leaching soil nutrients, and spilling toxic pesticides and fertilizers into soil and water systems. In short, deforestation contributes significantly to climate change, soil erosion, reduced soil fertility, and disruption of soil and water systems, causing undue harm to ecosystems and people.

2. Curing:

Curing refers to the process of drying the tobacco leaf. In this step, tobacco leaves are transported to a curing barn to be dried. A commonly used method for drying the tobacco leaf is “flue-curing.” Flue curing is when the leaves are hung into curing barns and dried from heated air. This approach requires flue-curing barns that are heated by externally fed fireboxes. A distinct odor, texture, and color develop as the leaves lose their moisture.

Small-scale tobacco farmers typically supply these fireboxes with wood chopped from forest reserves to feed these fireboxes. This reliance on wood for curing further contributes to deforestation, and burning this wood emits environmental pollutants, compromising air quality.

3. Processing and Trading:

In this stage, the cured tobacco leaves are sorted into grades and shipped to manufacturing plants. Many tobacco grades exist, and these are based on subjective visual characteristics such as stalk position, leaf size, texture, maturity, and color. This is a vigorous and highly labor-intensive activity because the quality inspection process and subsequent grade classification is done completely manually. Cured leaves must be sorted into homogeneous lots to be inspected. The whole process is contingent on one expert’s subjective assessment of the tobacco leaves. The grade a tobacco leaf receives determines the price a buyer would be willing to pay based on its determining value. Greenhouse gasses are emitted during the tobacco transportation and distribution process.

4. Manufacturing:

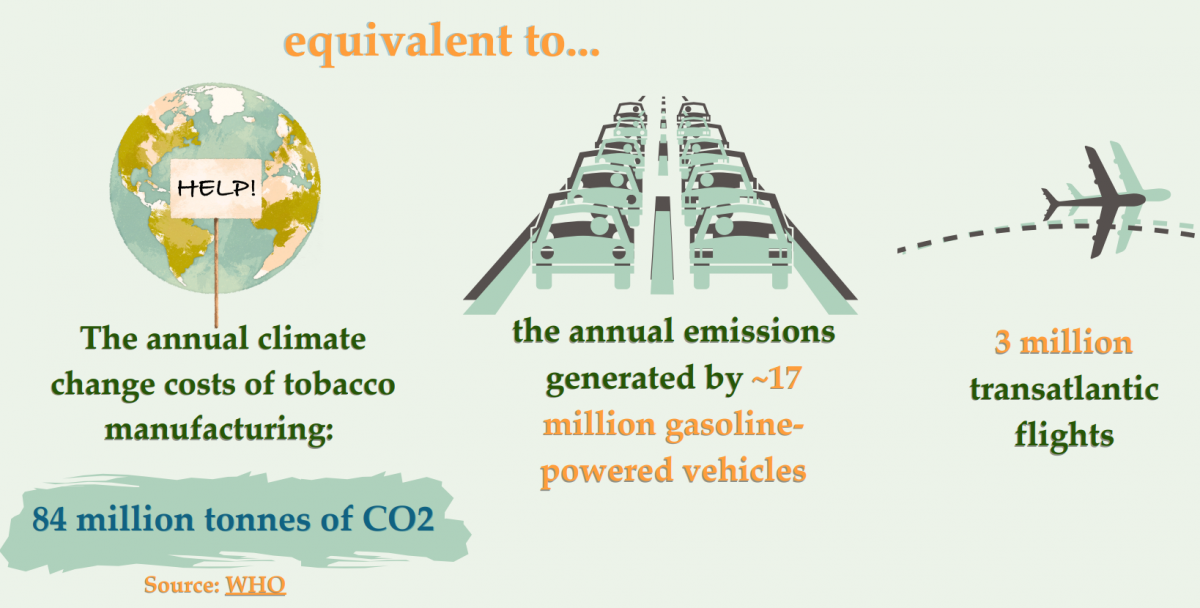

Tobacco is rolled into cigarette paper with filters and packaged for distribution. The manufacturing process also produces other waste products and emits greenhouse gases. According to the World Health Organization (WHO), 84 million tonnes of carbon dioxide (CO2) are emitted annually during manufacturing and into the environment.

5. Distribution:

Cigarettes are shipped to retailers to be sold. Similarly to stage 3 (processing and trading), greenhouse gasses are emitted during shipping. Importing and distributing tobacco leaves–from manufacturers to wholesalers and retailers–via various means of transport (air, boat, car, rail) generates a significant environmental burden.

6. Consumption:

Cigarettes are lit to be consumed. Smoke from cigarettes and other smoked tobacco products releases toxic chemicals into the air, causing undue harm to the environment and people. Greenhouse gases such as carbon dioxide, methane, formaldehyde, and nitrous oxides are also found in tobacco smoke; these chemicals have been found on surfaces months after smoking has ceased.

7. Disposal:

Improper disposal of cigarette butts on streets and sidewalks pollute the environment, particularly water systems. Given that up to two-thirds of cigarettes are improperly disposed of on the ground, these often end up in water systems. There are hundreds of thousands of cigarette butts polluting the ocean. Notably, only one cigarette butt in one liter of water–for a single day–will kill half of the fish exposed to that water for a mere four days. Cigarette filters constitute the second-highest form of plastic pollution worldwide. Not only are cigarettes and filters polluting the environment with plastic, but cigarette filters contain cancer-causing chemicals and other dangerous toxins, the long-term effects of which are still unknown.

Furthermore, most cigarette butt ingredients are not biodegradable and need light to break down, which can take up to a decade!

The costs of cleaning these littered tobacco products do not fall on the culprits–the tobacco industry–but on taxpayers. The numbers are staggering–it costs China nearly $3 billion, India roughly US $766 million, and South Africa approximately $117 million.

Alternative Crops to Tobacco

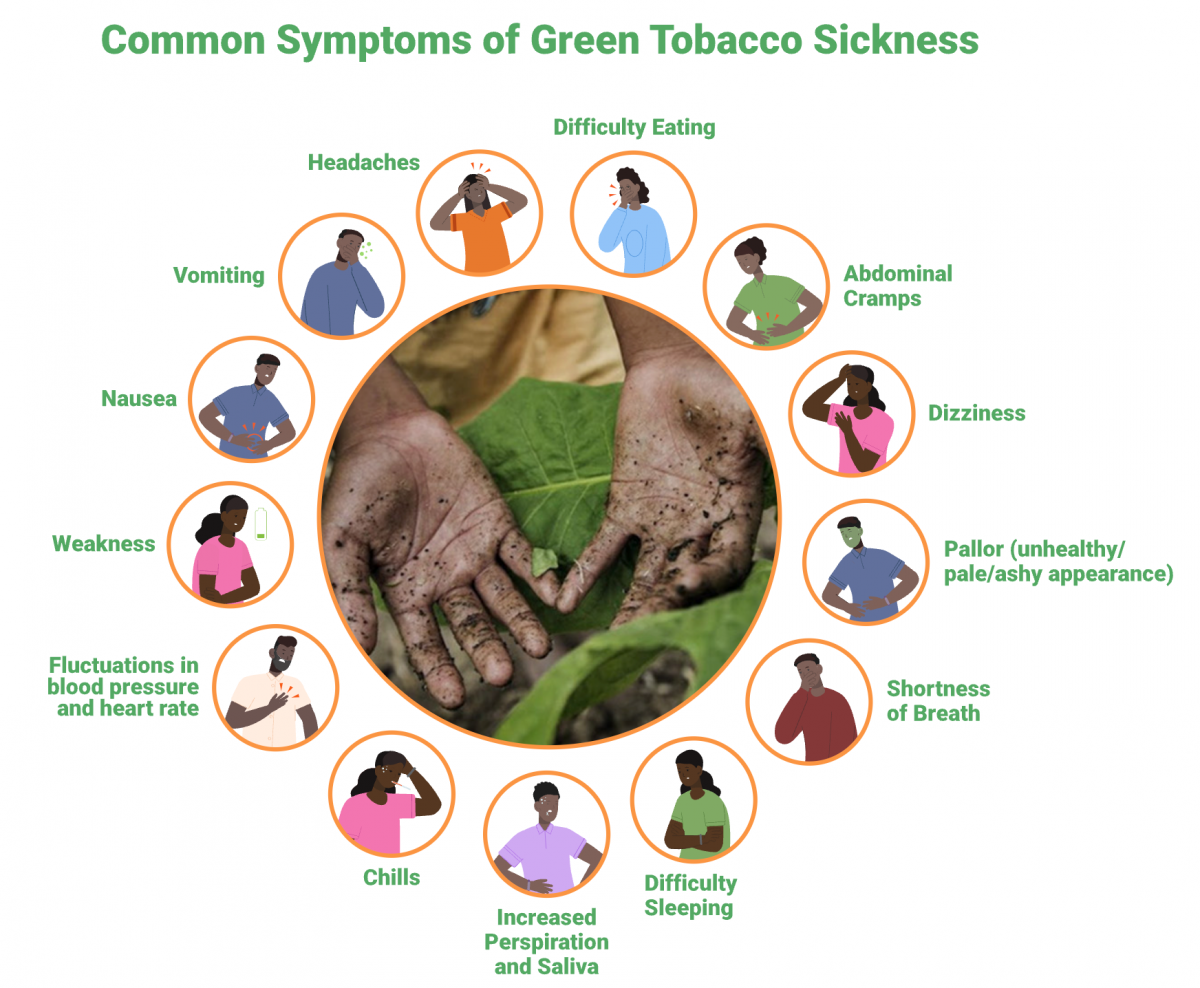

The tobacco crop drains more nitrogen, phosphorus, and potassium than comparable crops, making the soil unsuitable for growing different crops. Given that tobacco farming is labor-intensive and harvesting is done by hand, farmers are exposed to numerous agrochemicals that put them at risk of disease. Specifically, farmers and farm workers remain at risk of developing a form of nicotine poisoning known as “Green Tobacco Sickness,” caused by the transdermal absorption of nicotine from handling tobacco plants. Hand harvesting remains preferred because tobacco leaves mature at different rates, machinery is expensive, and leaves picked mechanically are of lower quality.

Illustration featured on TCDI Zambia Dashboard

Additionally, tobacco workers are highly susceptible to developing ‘tobacco worker’s lung’ and other respiratory diseases. Symptoms of respiratory disease include chest pain, rhinitis, and asthma. Breathing in tobacco mold and dust during curing, baling (compacting leaves into bales), storage (in the home, mainly), and sheeting (tying tobacco into burlap sheets) are some of the many causes of these respiratory problems.To enable the successful uptake of alternative plants, governments must address the array of factors influencing crop choices. These include (but are not limited to):

- Environmental: Land characteristics, types of soil, weather seasons, proximity to water sources, roads, and urban cities

- Farm and Household Characteristics: Household size, educational level, gender, farm equipment, land size, and food security.

- Financial, Technical, and Market Support: Assured markets, credit accessibility, extension services, and soil type sustainability.

Smallholder farmers in Africa often grow tobacco because it is perceived as one of the few economically viable crops. The promise of high returns, market stability, and incentives from the tobacco industry make it an attractive option. However, this perception is shaped by limited access to information, credit, and markets for alternative crops. Barring sufficient support from governments and NGOs, farmers may feel trapped in a cycle of dependency on the tobacco industry despite the environmental degradation and health risks involved.The Tobacco-Free Farms Project, a joint initiative between the World Health Organization (WHO), the World Food Programme (WFP), and several specialized agencies of the United Nations, was launched as a pilot project in Migori County, Kenya in 2022. The project aimed to help farmers sustainably transition from growing tobacco to alternative food crops that do not bear such a significant environmental and health burden and are backed by long-term market stability. By switching from tobacco to high-iron beans in Migori County, it was found that farmers are earning at least three times more!

Conclusion

In sum, the harms caused by tobacco products’ lifecycle–from the cultivating, curing, processing, and trading stages to the manufacturing, distribution, consumption, and disposal phases–are detrimental to the environment. The above mentioned effects are pervasive, impacting the earth’s air, water, land, and tobacco farmers. On this Clean Air for Blue Skies Day, we hope this piece underscores the need for governments and civil society to help farmers sustainably transition from growing tobacco to alternative food crops that do not bear such a significant environmental and health burden.

How useful is AI for development? Three things we learned from conversations with development experts

The development world is buzzing with excitement over the idea that new and emerging applications of artificial intelligence (AI) can supercharge economic growth, accelerate climate change mitigation, improve healthcare in rural areas, reduce inequalities, and more. But what does this look like in real life?

Here’s an example of this technology in action: WorldCoin, a cryptocurrency and digital identity platform, wants to scan the irises of every person in the world to develop an AI-powered system to tell robots from humans. This sounds like the beginning of a dystopian tale, but it’s not science fiction.

WorldCoin has already used its signature orb to collect biometric data from millions of people. And not surprisingly, the U.S./Germany-based company has run into regulatory troubles in many countries. In Kenya, for example, WorldCoin paid people around 7,000 shillings (just over $50 USD) to turn over their personal data, a practice which Kenya’s communication and data protection authorities labeled as “border[ing] on inducement.” WorldCoin’s activities were suspended in Kenya but are set to start again after a year-long government inquiry was recently dropped.

Regulatory challenges to the company’s activities are the highest profile example of what the Global Partnership for Sustainable Development Data’s network of partners are grappling with every day: namely, how to ensure that AI is deployed in development contexts in ways that help and don’t hurt people. Complementing these regulatory challenges are practical ones that arise in DG’s implementation work, for instance, how to audit a particular AI tool’s terms of reference and training datasets to assure its appropriateness for use in a development setting.

The Global Partnership and DG recently hosted a series of discussions with development practitioners on the real-life applications of AI and related technologies in international development. Eighty-four participants from local non-profits, international NGOs, and philanthropic and academic institutions attended the online sessions from around the world.

The purpose of these dialogues was to create a space for partners to share how they are thinking about AI and related technologies, including the opportunities and challenges they’re facing and practical examples of these tools on the ground. The three sessions were focused on distinct topics, namely: agriculture, climate, and health; conventional and new media; and Digital Public Infrastructure and digitization—three areas where we knew of existing examples of practical applications of AI among our partners. Across sectors, concerns emerged about the challenges of adapting digital technologies to development contexts and the power imbalances inherent to these activities, as illustrated in the WorldCoin example. But, overall, partners expressed a sense of optimism for the potential of AI-powered tools to provide solutions tailored to specific contexts, if we can overcome three key challenges.

What we mean when we talk about “AI in development”?

When we talk about AI, we’re often referring to a broad range of computer-based systems that can perform complicated tasks that we would normally expect humans to do, like solving problems, diagnosing illnesses, reasoning, and generating novel images or text. (Here’s a brief explainer from the Simon Institute for Long-Term Governance.) During the online dialogues, participants shared examples of applying AI, machine learning, and related new tech tools in their sectors. Some examples included: AI-powered chatbots for healthcare workers using Large Language Models, forecasting technology trained on historical data to alert farms to upcoming shocks, using machine learning to analyze geospatial data for national agricultural policy, and more.

Three challenges emerged during the dialogues to building and using AI to advance development goals. These were:

1. The push to develop and apply AI to development challenges largely ignores questions about when—or whether—AI is useful.

Participants described sensing pressure—whether from policymakers, development partners, or funders—to seek out applications of AI in their fields. But they cautioned against seeing AI as a one-size-fits-all solution. In fact, there are limited situations where AI tools can currently provide helpful solutions. For example, chatbots that can help people without access to healthcare receive diagnoses and recommend treatments do not guarantee that medication or treatment will be available, accessible, or affordable. Because AI tools are best applied in the context of larger development efforts, there’s a need to make sure AI development is demand-driven with the needs of end users in mind and deployed in the context of wider, well-resourced programs.

2. Access to appropriate training data is a barrier to creating AI tools to serve the most vulnerable.

Developing AI tools requires large amounts of training data. Ensuring that this data is representative of end users is a key challenge in development, especially because many of the people who are targets of development efforts do not have access to digital tools to generate data to train AI models. AI-powered tools generate analytics, text, or images based on the data they are trained upon. So, if you’re not in the data, the solution proposed by an AI tool won’t necessarily apply to your situation. One way to approach this, participants proposed, is by using intermediaries to collect data in the field. For example, having farmers use mobile (not smart) phones to text data to an intermediary that collects this data and transforms it into data for AI. But this is time consuming and costly. Data sharing could be one answer to this problem. But much of the existing data that could be used to develop AI tools is held by organizations, companies, or governments who are not incentivized or equipped to share it.

3. Decision-makers lack the knowledge needed to regulate and deploy AI tools.

Participants described a gap in skills and knowledge between the people who understand and develop this technology and the policymakers who have to make the decisions about whether and how to deploy and govern it. Bridging this gap requires democratizing information about AI tools, participants said, but most organizations don’t seem interested in funding or engaging in this work.

Moreover, policymaking silos structured around traditional sectors such as health, agriculture, or climate inhibit the potential deployment of AI tools to help identify trends across sectors. A case in point relates to climate change trend analysis and forecasting, which requires inputs from multiple sectors. If the policy and institutional structures are not designed to facilitate data sharing, then the opportunity to apply automated analysis and tools to solve cross-cutting problems such as climate change may well be missed.

How can we ensure AI tools are developed and used in fair and human-centered ways?

As governments and organizations grapple with how best to regulate AI, it’s clear that many people feel left out of these conversations and are concerned with putting safeguards in place to protect people and prevent harm before it’s too late. As one participant put it, “AI cannot be a positive force without addressing issues of ownership and inclusion.”

This is an especially complex question within development contexts, as the WorldCoin example above highlights. Can individuals anywhere in the world, who have very little understanding of complex AI systems, truly consent to their personal data being used to train algorithms? How should people be incentivized to contribute much-needed data to AI training? When do financial incentives become ‘inducement’ to participate? How do we measure or balance the benefits of AI tools against potential harms?

These are complex questions that require inclusive and participatory exploration on a context-by-context basis. Involving practitioners, like those who joined the AI Dialogues Series, is one step in the right direction to ensure AI can become a useful tool. We invite you to weigh in on these questions or to suggest some of your own. Please reach out to jmclaren@data4sdgs.org and torrell@developmentgateway.org to stay connected to this work.

These conversations will continue in 2024 through a series of online peer exchanges focused on AI for inclusive development that will be open for anyone to join. To ensure you receive an invitation to register, make sure you’re signed up for the Global Partnership’s listserv. You can join by emailing info@data4sdgs.org.

At a Glance | Tracking Climate Finance in Africa: Political and Technical Insights on Building Sustainable Digital Public Goods

Development Gateway: An IREX Venture’s (DG’s) “At a Glance” series explores the highlights in DG’s white papers and other publications. In this installment of the series, we explore the white paper titled “Tracking Climate Finance in Africa: Political and Technical Insights on Building Sustainable Digital Public Goods,” which was written by Dr. Catherine Weaver from the University of Texas at Austin and Tom Orrell, previously of DataReady and now a Deputy Director of Programs at DG. Weaver and Orrell explore the importance of climate finance tracking (CFT), common barriers to establishing climate finance tracking systems, and five insights on developing climate finance tracking systems.

What is Climate Finance and a Climate Finance Tracking system?

In order to combat the effects of climate change, financing is needed to fund effective climate fighting strategies, including funding to develop tools, programming, etc. that aim to equip governments and communities to predict, prevent, and address the needs provoked by climate change. Overall, climate finance is funding aimed at not only bringing the world closer to compliance with such climate policy as the 2015 Paris Agreement but is also aimed at protecting individuals and communities who are particularly vulnerable to the impacts of climate change. A climate finance tracking system is the planned process(es) and infrastructure supporting the tracking and monitoring of climate financing so that its impact can be tracked, analyzed, and (when appropriate) advanced or duplicated.

The first barrier to climate finance and creating a climate finance tracking system is that the definition of climate finance is often subject to debate because of politically motivated contestation and ambiguity over what activities are directly or indirectly motivated by climate change concerns. Therefore, the first step in establishing a climate finance tracking system is arriving at a consensus amongst stakeholders (including countries, international organizations, the private sector, and civil society) on what counts as climate change activity.

Once a common definition of climate change activity—and therefore, what constitutes climate finance—is established, a climate finance tracking system is needed in order to ensure climate finance is appropriately utilized and to track impact. While the specifics of what a climate finance tracking system looks like depends on the context in which it’s established, such a system can include tools like DG’s Aid Management Platform, an open-source tool that facilitates the monitoring of development activities in order to enhance aid effectiveness by allowing stakeholders to track activities from planning to implementation, and GIZ’s TruBudget, a collaborative and secured platform to track and coordinate the implementation of donor-funded investment projects. (Learn more about these tools and climate finance here.)

However, in order for any tools in a climate finance tracking system to be effective, the context in which the system is being established will ideally have many components, including digital infrastructure, human and computational capacity, data and accounting literacy, and complementary institutions and policies to ensure climate data is usable and useful for decision-making. Therefore, significant resources are needed in order for a climate finance tracking system to be effectively implemented. Here is an overview of five insights DG has identified on how best to create a climate finance tracking system.

- Creating a climate finance tracking system is not only a technical endeavor but also a political one. Any type of data, including climate finance data, is inherently political. Therefore, in order to build a viable and sustainable climate finance tracking system, stakeholders must first and foremost approach this as a political task.

- Building a climate finance tracking system will involve reaching consensus on how to standardize definitions, measurements, methods of reporting, and other data requirements. In the instance of climate finance tracking, the list of stakeholders to be included in this endeavor is long, as public, private and civil society stakeholders may express different needs and preferences when it comes to tracking and reporting data.

- Building a climate finance tracking system at the national level requires (a) a concerted investment of time and resources to create accessible and usable technical systems that capture critical information as well as (b) the human capacity and (c) political willingness to sustain it.

- Ensure different budgetary tools are interoperable (i.e., data can be shared seamlessly between systems) in order to avoid data silos and to facilitate the exchange of information between aid, procurement, budget, and other data systems in the climate finance tracking system.

- Creating climate finance tracking systems requires planning from the subnational to the transnational levels. Subnational political will and capacity will have to be carefully cultivated as this is where most money is spent. At the national level, efforts to build robust climate finance tracking systems will also need to coordinate with efforts at transnational levels, especially to empower the tracking of regional resources and spillover effects of national programs.

Dive deeper into these insights and learn more about climate finance tracking and climate finance tracking systems in the white paper.

Explore our white papers

Demystifying interoperability

This paper discusses, in practical terms, what goes into implementing interoperable solutions in partnership with public administrations. Based on 20+ years of DG’s experience, the paper demystifies key components needed to build robust, resilient, and interoperable data systems, focusing on the “how” of data standardization, data governance, and implementing technical infrastructure.

Evidence-Informed Policymaking: Education Data-Driven Decision Mapping in Kenya and Senegal

Between December 2022 and February 2024, Development Gateway: An IREX Venture (DG) and IREX, funded by the William & Flora Hewlett Foundation, conducted research in Kenya and Senegal to explore the complexities of education data supply, access, and decision-making processes. Effective decision-making in education relies on reliable, comparable, and accessible data managed through efficient information systems, facilitating resource optimization and goal monitoring. However, many countries, including Kenya and Senegal, experience challenges with unreliable education data, limited data utilization for decision-making, and insufficient national capacity to manage and leverage data effectively. The research, employing DG's Custom Assessment and Landscape Methodology (CALM), involved a desk review, stakeholder consultations, interviews, and validation workshops. Rather than an evaluation or comprehensive diagnostic, the study aimed to gather diverse perspectives and stories from stakeholders to contribute to ongoing discussions, technical investments, and reform efforts. We present key findings in Kenya and Senegal, before comparing and identifying shared characteristics that may be useful to assess in other country contexts.

Élaboration De Politiques Fondées Sur Des Données Probantes: Élaboration De Politiques Fondées Sur Des Données Probantes

Entre décembre 2022 et février 2024, Development Gateway : an IREX Venture (DG) et IREX, avec le financement de la Fondation William & Flora Hewlett, ont mené des recherches au Kenya et au Sénégal pour étudier la complexité des mécanismes de fourniture des données sur l'éducation, l'accès aux données et les processus de prise de décision. Une prise de décision efficace dans le domaine de l'éducation repose sur des données fiables, comparables et accessibles, gérées par des systèmes d'information tout aussi efficaces, facilitant ainsi l'optimisation des ressources et le suivi des objectifs. Cependant, de nombreux pays, dont le Kenya et le Sénégal, sont confrontés à des défis liés au manque de fiabilité des données sur l'éducation, à une utilisation limitée des données dans la prise de décision et à la faiblesse de la capacité nationale à gérer et à exploiter les données de manière efficace. Cette étude, qui utilise la méthodologie CALM (Custom Assessment and Landscape Methodology) de DG, comprend un examen documentaire, des consultations avec les parties prenantes, des entretiens et des ateliers de validation. Plutôt que de réaliser une évaluation ou un diagnostic complet, l'étude visait à recueillir des points de vue et des récits diversifiés auprès des parties prenantes afin de contribuer aux discussions en cours, aux investissements techniques et aux réformes entreprises. Nous présentons les principaux résultats obtenus au Kenya et au Sénégal avant de comparer et d'identifier les caractéristiques communes qui pourraient s’avérer utiles d'évaluer dans d'autres contextes nationaux.

Raising Awareness on World No Tobacco Day 2024: DaYTA/TCDI’s Work on Tobacco Industry Interference

This year, the World Health Organization (WHO) has designated the theme for World No Tobacco Day (WNTD) as ‘protecting children from industry interference’. The topic is more timely than ever, particularly in the African context that Development Gateway: An IREX Venture (DG) operates in through the Data on Youth and Tobacco in Africa (DaYTA) program and the Tobacco Control Data Initiative (TCDI).

For one, African countries are home to an extremely youthful populace. In Nigeria, over 50 percent of the population is under the age of 18, while in the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC), over 60 percent of the population is under the age of 24.

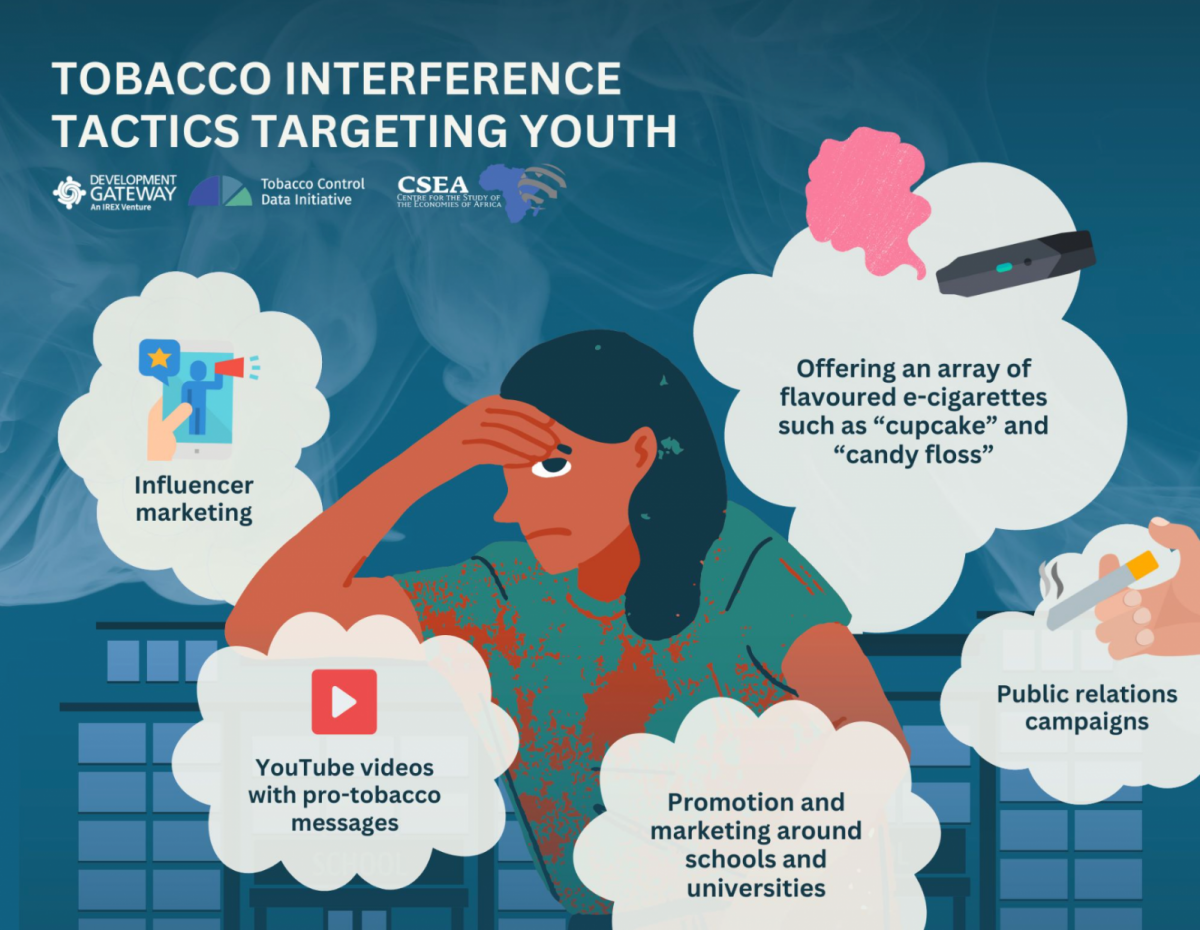

Over the years, the tobacco industry in Africa has successfully thwarted legal and institutional measures to combat its interference through a creative suite of tactics. The historical deception surrounding the tobacco industry’s representation of smoking’s adverse public health impacts has diminished its credibility amongst policymakers and civil society. As a result, the industry players have reverted to the use of front groups (i.e., manufacturers, media/PR firms, farmers associations, etc.), exploitation of public opinion, aggressive lobbying, and conflicts of interest to gain influence and repair its social image in the public eye.

Through the DaYTA program, DG is gathering primary data on tobacco use rates and trends among 10-17-year-olds in Kenya, Nigeria, and the DRC. This research will include new and emerging nicotine and tobacco products, such as electronic nicotine and non-nicotine delivery systems and heated tobacco products. Additional data gaps the DaYTA program seeks to fill include the socio-behavioral influences motivating minors to initiate tobacco use, as well as the nature of youth interactions with tobacco industry marketing.

In the DRC context, having data on prevalence is especially crucial. Presently, the only youth prevalence data available comes from the Global Youth Tobacco Survey (GYTS), conducted in 2008. In addition, this dataset is limited to in-school youth in urban areas, excluding two major demographics: out-of-school and rural youth.

Through the TCDI program’s ongoing comprehensive work filling tobacco data gaps in six countries, DG has enabled tobacco control stakeholders to combat tobacco industry interference using legislative and regulatory mechanisms. For example, during a recent meeting held in the DRC, tobacco control stakeholders from the WHO, civil society organizations, and various departments of the Ministry of Health (MoH) reiterated the need to utilize results from TCDI’s primary research on illicit trade, to support efforts to ratify the Protocol for the Elimination of Illicit Tobacco Trade in the DRC parliament. Notably, in 2023, then Prime Minister, Sama Lukonde, issued a ministerial decree (040) banning smoking in public places.

The tobacco industry has devised and deployed a number of creative strategies to target young people–advertising near schools and playgrounds, giving away products for free, and selling appealing flavors in new and emerging tobacco products. During the DaYTA program’s rapid assessment in the DRC, stakeholders explained that one of the ways the tobacco industry captures children’s attention is by leveraging the use of toys and sweets. Specifically, they indirectly advertise near schools by selling candy mimicking the appearance of a cigarette, including the names and packaging of major cigarette brands. This subliminal messaging may lead children to become curious about real tobacco products, encouraging consumption later in life.

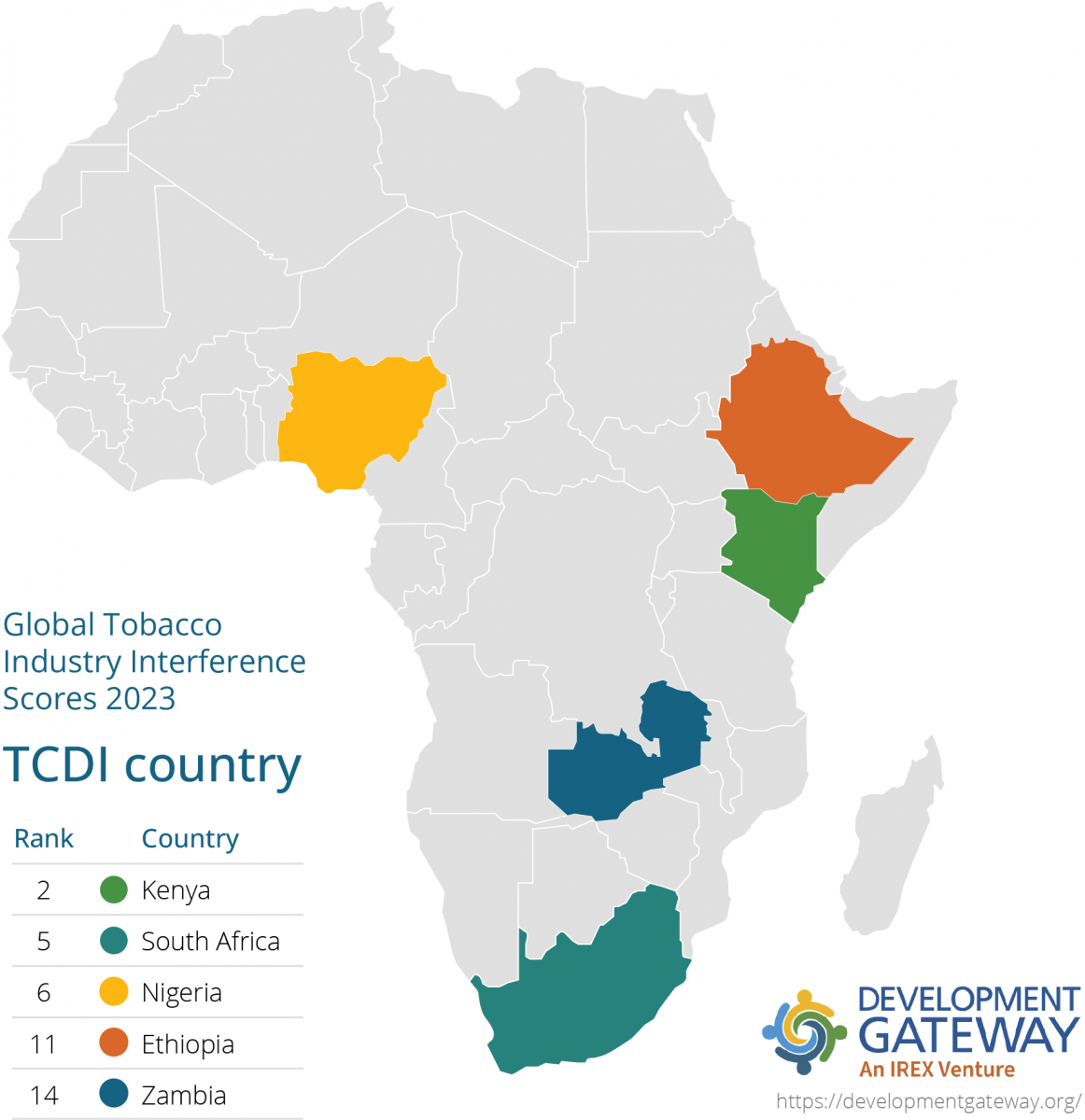

Since the TCDI program began in 2019, the number of African countries participating in the Global Tobacco Industry Interference Survey has steadily increased–from a mere 5 countries in 2019 to 20 in 2023. This survey details how governments are responding to tobacco industry interference and how closely governments are adhering to the requirements stipulated by the WHO’s Framework Convention on Tobacco Control (FCTC).

The research and knowledge base stemming from the TCDI program has highlighted a host of recommendations to tobacco control stakeholders on how to address the industry interference, including but not limited to:

- Require transparency from the tobacco industry. Ensure the public has access to tobacco industry information, such as disclosures. This facilitates openness and accountability.

- Establish a provision of standards or code of conduct to regulate interactions between public officials and the tobacco industry. For instance, an official or state employee should not accept gifts or services, in cash or in-kind, from the tobacco industry. Moreover, governments should not accept, support, or endorse any voluntary code of conduct put forth by the tobacco industry in place of legally binding tobacco control measures.

- Reject any and all partnerships with the tobacco industry, especially when it involves the industry attempting to position itself as a socially responsible stakeholder through engagement in corporate social responsibility activities.

- Enforce Monitoring & Enforcement mechanisms such as penal sanctions and whistleblower policies.

- Avoid granting preferential business treatment to the tobacco industry.

As youth represent one of the most vulnerable populations being targeted by aggressive marketing of retail nicotine and tobacco products, it is imperative that interventions to combat tobacco industry interference can be pursued and implemented effectively. The six TCDI focus-country dashboards remain an excellent resource for stakeholders to expose lies perpetuated by the tobacco industry. For example, in many African countries, the stakeholders claim that tobacco control laws are unconstitutional or infringe on international trade and investment agreements. This is categorically false, as the WHO FCTC represents a legal basis for the policies being challenged, as there exists an international consensus on the adverse effects of tobacco use.

On this year’s World No Tobacco Day, DG is more cognizant than ever of the importance and impact of our tobacco control portfolio. Our longstanding efforts to equip policymakers, civil society, and the general public with access to timely and relevant data aids in facilitating sound decision-making, bolstering public trust, and creating opportunities for youth participation. Access to timely, accurate, and context-specific data on adolescent tobacco use is essential for cementing a robust tobacco control framework, one that can proactively combat tobacco industry interference, particularly in policymaking processes.

Share

Recent Posts

Shared Struggles, Shared Solutions: Education and Cross-Sector Data Use Insights

This blog draws on DG’s experience in climate, health, aid management, and agriculture to explore connections between the challenges of data collection, data hosting, and data governance across different sectors and what the solutions to overcoming them can teach us about strengthening education data systems.

Economic Toll of Tobacco-Related Diseases in Kenya: New Research Findings

Development Gateway: An IREX Venture (DG) is pleased to announce the publication of a research manuscript on the Economic Costs of Tobacco-Related Illnesses in Kenya. This research was carried out as part of the Tobacco Control Data Initiative (TCDI) activities in Kenya and is part of a broader report on Morbidity and Mortality from Tobacco Use in Kenya.

The Data Crisis Following USAID’s Withdrawal: Opportunities to Reimagine Data Systems

For decades, USAID and other US government funding supported global data systems, from health surveys and early warning tools to digital infrastructure for ministries. The abrupt termination of USAID funding has triggered twin crises: a halt to data collection and the undermining of digital systems – reveal existing inefficiencies and instabilities in how data is collected, managed, and shared both within and between countries.

Letting the Sunshine in: Building Inclusive, Accountable, and Equitable Climate Finance Ecosystems

In late April 2024, Development Gateway: An IREX Venture, together with the Thai Youth Anti-Corruption Network, organized an invite-only roundtable in Bangkok, Thailand to discuss how to efficiently and effectively use climate financing, which is money committed for activities to mitigate or adapt to the impacts of climate change.

Participants of the roundtable, hosted by the HackCorruption project led by Accountability Lab, came from a broad range of local, regional, and global civil society organizations; media; and private sector, academic, and development partner organizations. Together, we explored the concept and current execution of climate financing strategies. How do we define, access, monitor, and assess the impact of these financial flows?

Ultimately, the group determined that ensuring funds allocated to curb the negative impacts of climate change have the greatest impact requires a multi-disciplinary and multi-stakeholder approach that prioritizes local contexts, inclusive governance, transparency, accountability, and equitable distribution of resources.

Disparate but Necessary Efforts: The Current State of Climate Financing

The current state of climate financing—in short—is a mess.

At COP28 in 2023, climate finance was at the forefront. Several member states, notably developing countries, highlighted the need to lean into climate finance transparency and develop rigorous national climate finance tracking frameworks. Public, private, and blended funding and financing mechanisms are proliferating around the globe in a sea of market and regulatory experimentation. From carbon taxes, trading, and capture schemes to direct subsidies, governments and international organizations are simultaneously pursuing multiple (sometimes untested) funding and financing approaches.

While these necessary but disparate efforts continue to evolve, fundamental questions about climate finance remain unanswered. For instance, what investments constitute climate investments? How do we track financial flows and market activity while avoiding double counting investments? How do we ensure that investments in certain climate mitigation strategies are not harming the people living in areas that it is intended to help? The absence of agreed global standards and classifications regarding this cornerstone issue makes it challenging to track and measure what types of initiatives provide the greatest return on investment and positive environmental impact.

Additionally, a shared understanding of how climate investments are monitored and how impacts are tracked is critical to understand progress toward the legally binding commitment UN Member States made at the Conference of the Parties to the UN Climate Change Conference in 2015 (COP21 Paris) to hold “the increase in the global average temperature to well below 2o C above pre-industrial levels [and aim] to limit the temperature increase to 1.5 o C above pre-industrial levels.”

The cost of meeting this commitment is astronomical. The Climate Policy Initiative’s most recent estimates for meeting the Paris Agreement, “range from USD 5.4 trillion to USD 11.7 trillion per year until 2030, and between USD 9.3 trillion and USD 12.2 trillion per year over the following two decades.” This comprises funds allocated for the transformation of energy systems, restoring and protecting natural resources as well as methane abatement, increased resilience, and coping with damage.

The 100 trillion-dollar question: how do we ensure good governance of climate finance mechanisms and data flows?

Shining light on climate finance and ensuring that it is used for positive change requires inclusive, accountable, and equitable systems. In the absence of clear global standards of how climate finance can be used to create positive social and environmental impacts, the priorities and needs of local contexts must take precedence to ensure that investments achieve desired impact and that solutions are locally owned as well as locally beneficial. Discussions with representatives of civil society organizations in Thailand highlighted the uneven and messy execution that can occur with climate projects aimed at outcomes aligned with donor priorities that are sometimes in opposition with those of communities.